The marketplace of ideas refers to the belief that the test of the truth or acceptance of ideas depends on their competition with one another and not on the opinion of a censor, whether one provided by the government or by some other authority.

Concept is economic analogy

This concept draws on an analogy to the economic marketplace, where, it is claimed, through economic competition superior products sell better than others. Thus, the economic marketplace uses competition to determine winners and losers, whereas the marketplace of ideas uses competition to judge truth and acceptability. This theory of speech therefore condemns censorship and encourages the free flow of ideas as a way of viewing the First Amendment.

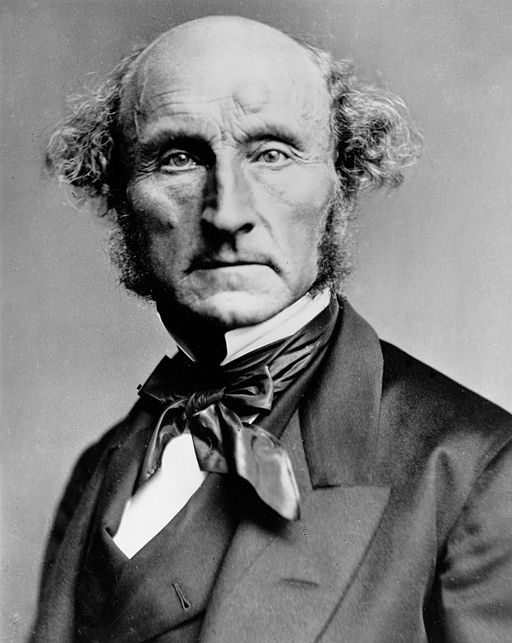

John Stuart Mill originated concept

Perhaps the origins of translating market competition into a theory of free speech was John Stuart Mill’s 1859 publication On Liberty. In Chapter 2, Mill argues against censorship and in favor of the free flow of ideas. Asserting that no one alone knows the truth, or that no one idea alone embodies either the truth or its antithesis, or that truth left untested will slip into dogma, Mill claims that the free competition of ideas is the best way to separate falsehoods from fact.

Court has invoked the marketplace concept as a theory of free expression

The first reference to the marketplace of ideas was by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. in Abrams v. United States (1919). Dissenting from a majority ruling that upheld the prosecution of an anarchist for his anti-war views under the Espionage Act of 1917, Holmes stated: “But when men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas — that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out.”

Since this first appeal to the marketplace of ideas as a theory of free expression, it has been invoked hundreds if not thousands of times by the Supreme Court and federal judges to oppose censorship and to encourage freedom of thought and expression. The Court invoked the phrase in McCreary County v. American Civil Liberties Union (2005) to strike down a religious display of the Ten Commandments in front of a courthouse, in Randall v. Sorrell (2006) to invalidate expenditure limits for candidates for political office, and in Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union (1997) to bar enforcement of the Communications Decency Act in censoring the content of material distributed on the Internet and the Web.

More recently, the Court invoked the phrase several times in Matal v. Tam (2017), the decision invalidating a provision of federal trademark law that prohibited disparaging trademarks. Both Justice Samuel Alito in his majority opinion and Justice Anthony Kennedy in his concurring opinion referenced the marketplace of ideas.

The Court used the phrase in Walker v. Sons of Confederate Veterans (2015), explaining that “government statements do not normally trigger the First Amendment rules designed to protect the marketplace of ideas.”

Justice Stephen Breyer also invoked the metaphor in his concurring opinion in Reed v . Town of Gilbert (2015), writing that “whenever government disfavors one kind of speech, it places that speech at a disadvantage, potentially interfering with the free marketplace of ideas and with an individual’s ability to express thoughts and ideas that can help that individual determine the kind of society in which he wishes to live, help shape that society, and help define his place within it.”

Overall, the marketplace of ideas analogy has become a powerful idea, underpinning much of First Amendment jurisprudence. It remains perhaps the most pervasive metaphor to justify broad protections for free speech.

This article was originally published in 2009. David Schultz is a professor in the Hamline University Departments of Political Science and Legal Studies, and a visiting professor of law at the University of Minnesota. He is a three-time Fulbright scholar and author/editor of more than 35 books and 200 articles, including several encyclopedias on the U.S. Constitution, the Supreme Court, and money, politics, and the First Amendment.