Legal challenges to the imposition of taxation of newspapers in America go all the way back to the eve of the Revolutionary War. In fact, one of the immediate situations provoking the War was the British attempt to tax the sale and distribution of newspapers and legal documents through the Stamp Act. Because the tax had been imposed by the British parliament, the colonists based their protest on the principle of “no taxation without representation.” Controversies that have emerged since the writing of the First Amendment, and its subsequent application to the states via the Fourteenth Amendment, have largely focused on taxation used to penalize certain publications.

Court struck down differential newspaper taxes

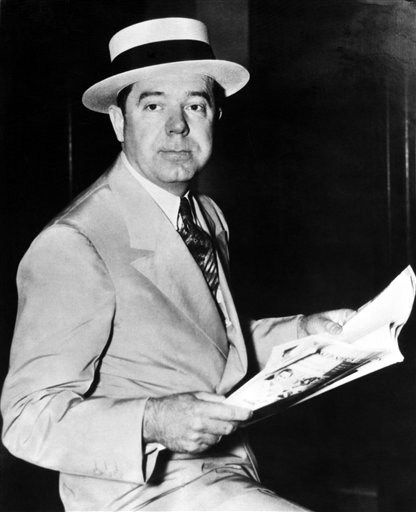

The leading case in this area of law is Grosjean v. American Press Co. (1936). A unanimous U.S. Supreme Court struck down a 2 percent license tax that the state of Louisiana— then largely dominated politically by its former governor and then U.S. senator, Huey Long—had imposed on the gross receipts of newspapers with circulations of more than 20,000 copies a week. The Court recognized that it was no coincidence that the tax fell largely on those newspapers critical of Long and his political allies. In writing the Court’s decision, Justice George Sutherland observed that newspapers were not “immune from any of the ordinary forms of taxation for support of the government” but also pointed out the dangers of differential taxation.

The Court reiterated this position in Minneapolis Star and Tribune Co. v. Minnesota Commissioner of Revenue (1983) when it struck down a Minnesota “use tax” on the cost of paper and products used by periodicals in excess of $100,000 a year. Because there were only eleven publishers—including the Minneapolis Star Tribune—that fit this description, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor feared that the tax was “facially discriminatory.”

Justice Thurgood Marshall came to a similar conclusion in writing the Court’s decision in Arkansas Writers’ Project, Inc. v. Ragland (1987). In this case, the Court overturned an Arkansas law that exempted some specialty publications from the state’s sale tax but not general interest magazines like the Arkansas Times. Marshall observed that “a power to tax differentially,as opposed to a power to tax generally, gives a government a powerful weapon against the taxpayer selected.” By contrast, Justice Antonin Scalia, joined by Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist, expressed the minority view that the state plan was little different from other subsidies that the Court had upheld.