In Teitel Film Corp. v. Cusack, 390 U.S. 139 (1968), the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of requiring the submission of films to censors prior to exhibition, but the majority only addressed the narrow question of “whether prior restraint was necessarily unconstitutional under all circumstances.” Having located the outer limits of the question, the Court dealt with the administrative details of America’s censorship regime in Teitel.

Censorship ordinance gave no time limit to return decisions on obscenity

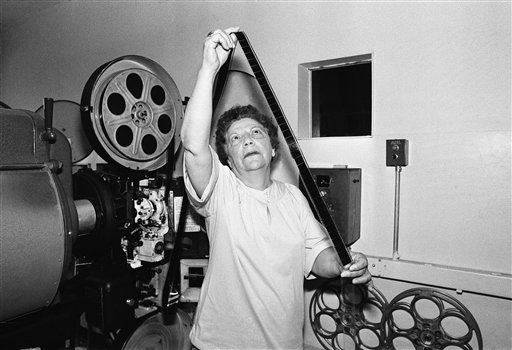

The Illinois courts had permanently enjoined Teitel Film Corp. from showing certain motion pictures in Chicago based on its Chicago Motion Picture Censorship Ordinance. The ordinance allowed 50 to 57 days to complete the administrative process, and there was no time limit on returning decisions regarding obscenity. The film company had challenged the ordinance as unconstitutional on its face and as applied.

Court struck down ordinance only because of the time-consuming review provisions

Without reaching the question of whether or not the films were obscene, the Supreme Court struck down Chicago’s ordinance because of its time-consuming provisions for review of the censorship board’s decisions. Citing Freedman v. Maryland (1965) for its authority, the Court’s per curiam opinion decreed that the implementation of censorship laws had to minimize the negative consequences of erroneous decisions. Censorship regimes had to include procedural safeguards and expeditious procedures that “obviate the dangers of a censorship system.”

Court created “bewilderment” through divergent censorship opinions

The same year as this decision, the Court in Interstate Circuit, Inc. v. Dallas (1968) ruled the city’s ordinance establishing the standards by which its Motion Picture Classification Board identified films that were not suitable for minors younger than 16 years of age unconstitutionally vague. In dissent, Justice John Marshall Harlan II complained that the Court’s decisions in this case and others dealing with censorship and obscenity had created nothing but “utter bewilderment” because of the fragmented and divergent opinions handed down by the Court.

This article was originally published in 2009. Roy B. Flemming is a Professor Emeritus in the Department of Political Science at Texas A&M University.