Sometimes courts protect freedoms articulated in the First Amendment without even citing the amendment. Indeed, during the debate over the Bill of Rights, Federalist defenders of the document had argued that such a bill was unnecessary because the federal government lacked power to deny such rights.

Largely relying upon the common law, the Supreme Court of Kansas in Anderson v. City of Wellington, 40 Kan. 173 (1888) took a similar approach to the powers of a municipality.

Kansas ordinance prohibited parades without mayor’s consent

In 1887, the city of Wellington, Kansas, adopted an ordinance. It made it “unlawful for any person or persons, society, association, or organization, under whatsoever name, to parade any public street, avenue, or alley . . . shouting, singing, or beating drums or tambourines, or playing upon any other musical instrument or instruments, or doing any other act or acts designed, intended, or calculated to attract or call together an unusual crowd or congregation of people upon any of said public streets, avenues, or alleys, without having first obtained in writing the consent of the mayor” or other public official.

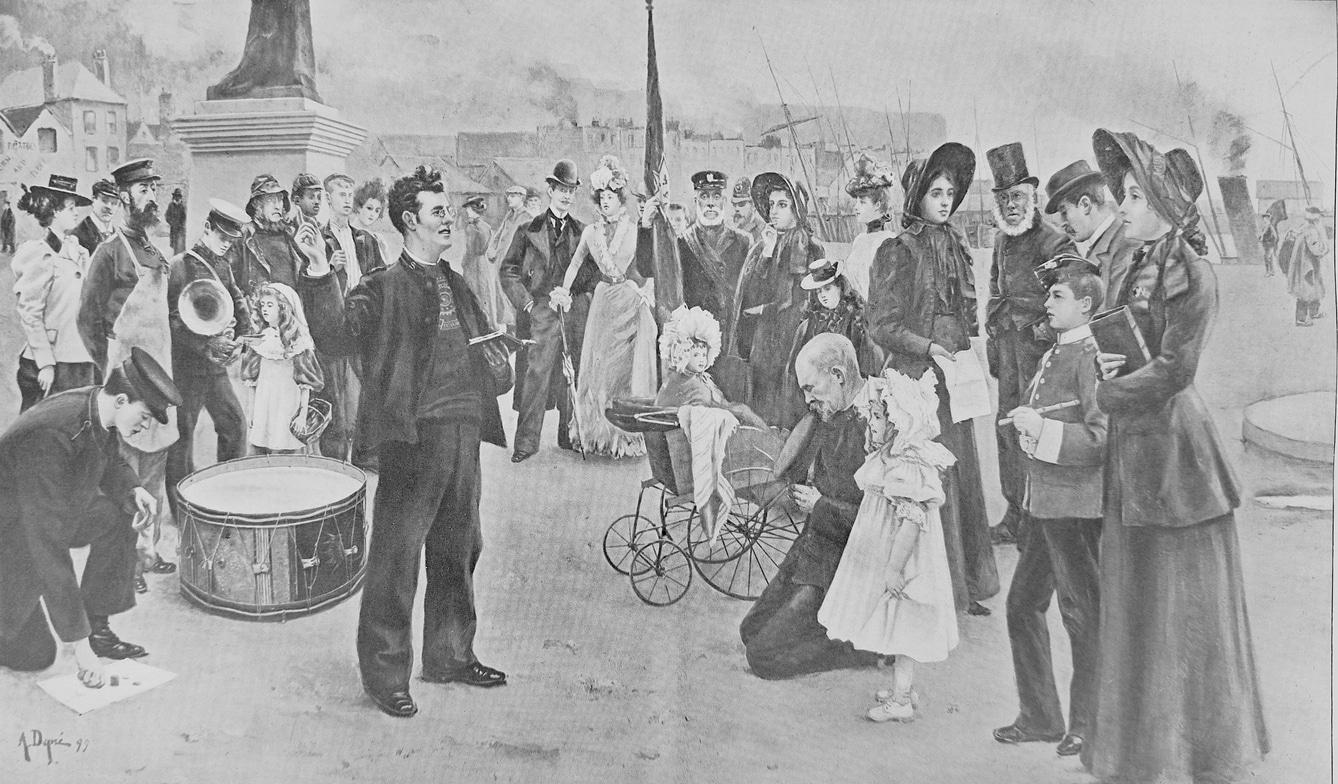

This ordinance was put to the test shortly thereafter when members of the Salvation Army, whom the law may have attempted to target (arguably in violation both of the Army’s free speech and religious free exercise rights), proceeded to hold such a parade. The participants were arrested and convicted both in the police and district court, and they appealed to the Kansas Supreme Court.

Kansas Supreme Court overturns convictions of Salvation Army members

In a unanimous decision written by state Supreme Court commissioner Benjamin Franklin Simpson, the court overturned these convictions in Anderson v. City of Wellington.

The opinion, which appears representative of the sentiment of the day (El Haj 204, 990-991), questioned the authority of the city to enact such an ordinance. More generally, it celebrated the right of peaceable assembly, which is guaranteed by the First Amendment, and which the U.S. Supreme Court later applied to the states in De Jonge v. Oregon (1937).

In questioning the city’s authority to enact this ordinance, the court said: “Powers encroaching upon the rights of the public or of individuals must be plainly and literally conferred by the charter,” which the state had granted to the city. Moreover, such ordinances “must be reasonable, not inconsistent with the laws of the state, not repugnant to the fundamental rights, must not be oppressive, must not be partial or unfair, must not make special or unwarranted discriminations, and must not contravene common right.”

‘Is a street parade…legally objectionable in itself?’

“Is a street parade, with music or singing, legally objectionable in itself, or does it threaten the public peace or the good order of the community?” the court asked.

It noted that, as written, Masons, Odd Fellows, and even “Sunday-School children,” fell under the ambit of the ordinance as would “a public address upon any subject being made on the streets.”

“A crowd of people is one of the most ordinary incidents of every-day life in any city of considerable size in this country,” the court said.

‘An abridgment of the rights of people’

The ruling characterized the ordinance as “an abridgment of the rights of the people. It represses associated effort and action. It discourages united effort to attract public attention, and challenge public examination and criticism of associated purposes. It discourages unity of feeling and expression on great public questions, economic, religious, and political. It practically destroys these great public demonstrations that are the most natural product of common aims and kindred purposes.”

The court observed that “Public parades of this character are not unlawful in their intent, purpose and result. They are not mala in se [inherently wrong]. If they are to be mala prohibita, it ought to be by some general law, and not by local regulation.”

Moreover, any such general laws should not give unlimited discretion to officials to choose which events to permit and which to prohibit, the court ruled. This sentiment is somewhat similar to modern doctrines prohibiting regulations that are not content or viewpoint neutral.

Some restrictions that might be permissible

Perhaps anticipating modern judicial acceptance of reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions, the court did concede that “It might be proper, on account of the peculiar conditions of affairs in a city, that street parades should be confined to certain streets, or should be conducted within certain hours of the day, or should be forbidden in the night-time, or that the police department should have some previous notice, or that there should be other reasonable regulations respecting them, justified by such a condition that it would be apparent that regulation, and not prohibition, was the object of the ordinance.”

In words that should please music lovers, it noted that “The use of musical instruments on such occasions are not specifically objectionable. Songs and shouts, cheers and the waving of banners, have always been considered as demonstrations of approval, and not as tending to create disturbances, or provoke breaches of the peace.”

A contrary precedent

Although this opinion was largely representative of 19th century law, in Commonwealth v. Abrahams, 156 Mass. 57 (1892), the Supreme Court of Massachusetts in Suffolk upheld a statute allowing commissioners of public parks in Boston to punish an individual for giving an oration in a public park, after park commissioners had denied his right to do so.

In that case, the court ruled that “The parks of Boston are designed for the use of the public generally; and whether the use of any park or a part of any park can be temporarily set aside for the use of any portion of the public is for the park commissioners to decide, in the exercise of wise discretion.”

John R. Vile is a political science professor and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University.