In Roake v. Brumley, the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in June 2025 invalidated a Louisiana law requiring all public schools to post the Ten Commandments in each classroom.

The judges unanimously decided that the Ten Commandments display “qualifies as a religious display,” and that such “government speech must comport with the Establishment Clause,” which forbids governmental endorsement of religion. Citing earlier cases dealing with prayer and Bible reading in schools, the judges stressed that posting the Ten Commandments subjected “impressionable school children” to “unwelcome religious exercises,” which, because they would encounter them in every classroom, they would have to assume “special burdens” to avoid.

Citing several dissenting opinions in prior cases involving religious displays, Louisiana had argued that the plaintiffs could not establish “offended observer standing.” The court noted that the Supreme Court had “never expressly and formally recognized” such standing in a majority opinion and observed that this case involved much more.

First Amendment's wall of separation between church and state

The judges noted, "Students will be subjected to unwelcome displays of the Ten Commandments for the entirety of their public school education. There is no opt-out option. Plaintiffs are not mere bystanders who have ‘fail[ed] to identify any personal injury suffered by them as a consequence of the alleged constitutional error, other than the psychological consequence presumably produced by observation of conduct with which they disagreed.’”

Instead, students “will be pressured to observe, meditate on, venerate, and follow this scripture and to suppress expression of their own religious beliefs and backgrounds at school.” The judges concluded that “Plaintiffs are more than mere ‘offended observers.’ Students and parents will be ‘directly affected.’”

Louisiana argued that the Supreme Court decision in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District (2022), which had upheld the right of a school coach to pray on the football field after a game, upheld the right of the state to post the Ten Commandments. Still, the circuit court judges observed that this “was primarily a Free Exercise Clause and Free Speech Clause challenge.”

The 5th Circuit continued to view the First Amendment’s establishment clause as erecting a wall of separation between church and state and as being especially applicable when it came to the education of elementary and secondary school children.

Although the court had moved away from the Lemon Test in the Kennedy case, it had not specifically overruled Stone v. Graham (1980), which had struck down the display of the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms. The court’s justified display of the Ten Commandments on state Capitol grounds in Van Orden v. Perry (2005) on historical grounds — but that case did not involve impressionable school children. As in Stone, Louisiana was not integrating the Ten Commandments into studies of history, civilization, or ethics but displaying them “indiscriminately” in every public school classroom, indicating that the state lacked a secular legislative purpose.

Further distinguishing this case from those involving opening public meetings with prayer, the court cited testimony by the plaintiffs indicating that “[t]here is no longstanding tradition of permanently displaying the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms in Louisiana or the United States more generally.”

The 5th Circuit judges rejected arguments that the district court had erroneously issued a preliminary injunction in this case. A concurring opinion further found that offended observers could not be denied standing in litigation or that the Supreme Court, in rejecting the Lemon Test in the Kennedy case, had abandoned its pre-existing parts.

Darcy Roake, an ordained minister in the Unitarian Universalist Church, and other plaintiffs brought the case on behalf of themselves and their children, against Cade Brumley, the Louisiana State Superintendent of Education responsible for implementing the law.

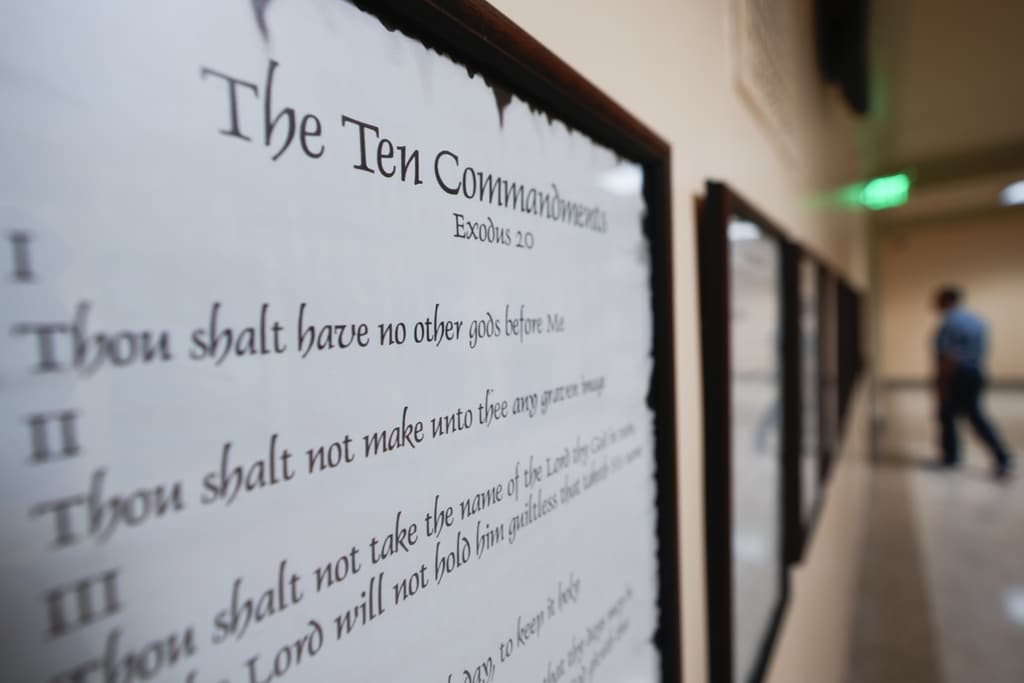

Provisions of Louisiana’s Ten Commandments law

Relevant parts of the law had provided that:

No later than January 1, 2025, each public school governing authority shall display the Ten Commandments in each classroom in each school under its jurisdiction. The nature of the display shall be determined by each governing authority with a minimum requirement that the Ten Commandments shall be displayed on a poster or framed document that is at least eleven inches by fourteen inches. The text of the Ten Commandments shall be the central focus of the poster of framed document and shall be printed in a large, easily readable font.

The law further specified that the specific version of the Ten Commandments should be taken from the Protestant King James Bible. Although many who supported the law did so in hopes of conveying a religious message, the law noted that Commandment displays should be accompanied by a statement indicating that “the Ten Commandments were a prominent part of American public education for almost three centuries.” As proof, it cited The New England Primer, circa 1688, the McGuffey Readers from the early 1800s, and texts that Noah Webster had published.

Implications

For now, the 5th Circuit case settles the issue on the Ten Commandments in Louisiana’s public schools. Should the Supreme Court decide to review the decision, it could provide further clarity about what, if any, component parts of the Lemon Test it plans to continue to apply in establishment clause cases.

Recent ambiguity over interpretation of establishment clause

The case has been important because of the current ambiguity that surrounds the interpretation of the establishment clause of the First Amendment in light of the decision by Justice Neil Gorsuch in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, 596 U.S. ____ (2022). In that case, the Supreme Court upheld the right of a high school coach to offer a prayer on the field after a football game and rejecting the long-established three-part Lemon Test.

The Lemon Test, adopted by the Supreme Court to ascertain establishment clause violations, had required laws to have a clear secular legislative purpose and a primary effect that neither advances nor inhibited religion, without promoting excessive entanglement between church and state. Gorsuch had also criticized the “endorsement test,” which had attempted to ascertain whether a reasonable observer would view laws dealing with religious expression as an endorsement of one or another religious view or practice.

Details of federal judge's decision in Louisiana case

Judge deGravelles issued his injunction against the posting of the Ten Commandments chiefly on his belief that the law violated the establishment clause of the First Amendment.

Citing a number of similarities between the Louisiana law and the Kentucky law that the Supreme court had invalidated in Stone v. Graham, the judge believed that, absent a contrary decision on the part of the Supreme Court, the Stone decision remained binding on him.

Citing Stone, he observed in particular that neither case represented a situation “in which the Ten Commandments are integrated into the school curriculum, where the Bible may constitutionally be used in an appropriate study of history, civilization, ethics, comparative religion, or the like.” He further noted that both laws “single out the Decalogue for central display while declining to give preferential treatment to foundational documents like the U.S. Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, or the Magna Carta.”

Judge deGravelles argued that, even if Stone did not apply, the Louisiana law remained unconstitutional under the Kennedy decision. More particularly, he did not believe that the state had shown that there had been a historical pattern of posting the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms. The judge believed that the display at issue was:

- sectarian, because it specified a particular Protestant version of the Commandments;

- discriminatory, because Jewish, Unitarian Universalist, and atheist plaintiffs said it did not include their perspectives; and

- coercive, because children were required to attend schools, where the Commandments would be displayed.

Judge examined decisions on religion in public schools, buildings

In addition to arguing that the decision in Stone v. Graham remained a viable precedent that had not been overturned by the decision in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, the district court judge distinguished the Louisiana law from other cases.

These included:

- Van Orden v. Perry, 545 U.S. 677 (2005), which had involved a monument with the Ten Commandments in a public park;

- Town of Greece v. Galloway, 572 U.S. ____ (2014), which had upheld public prayers prior to a New York town meeting; and

- a variety of lower court decisions that had addressed the words “In God We Trust” in the pledge to the flag and other matters.

The court emphasized the public-school context of the Louisiana law and the fact that students were compelled to attend and therefore constituted something of a “captive audience.”

The court accepted the expert testimony that had been offered by Professor Steven K. Green, a professor of history and religious studies at Willamette University in Salem, Oregon, in disputing the argument that public schools had a long history of displaying the Ten commandments in classrooms. It also used the testimony of the law’s legislative supporters to show that many of them adopted the law for the specific purpose of inculcating religious principles and Judeo-Christian values.

John R. Vile is a political science professor and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University.