The story of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old African-American who was brutally murdered in Mississippi in 1955 after being accused of flirtatious behavior toward a white woman, has been told many times, in books, documentaries and recently in the 2022 film Till.

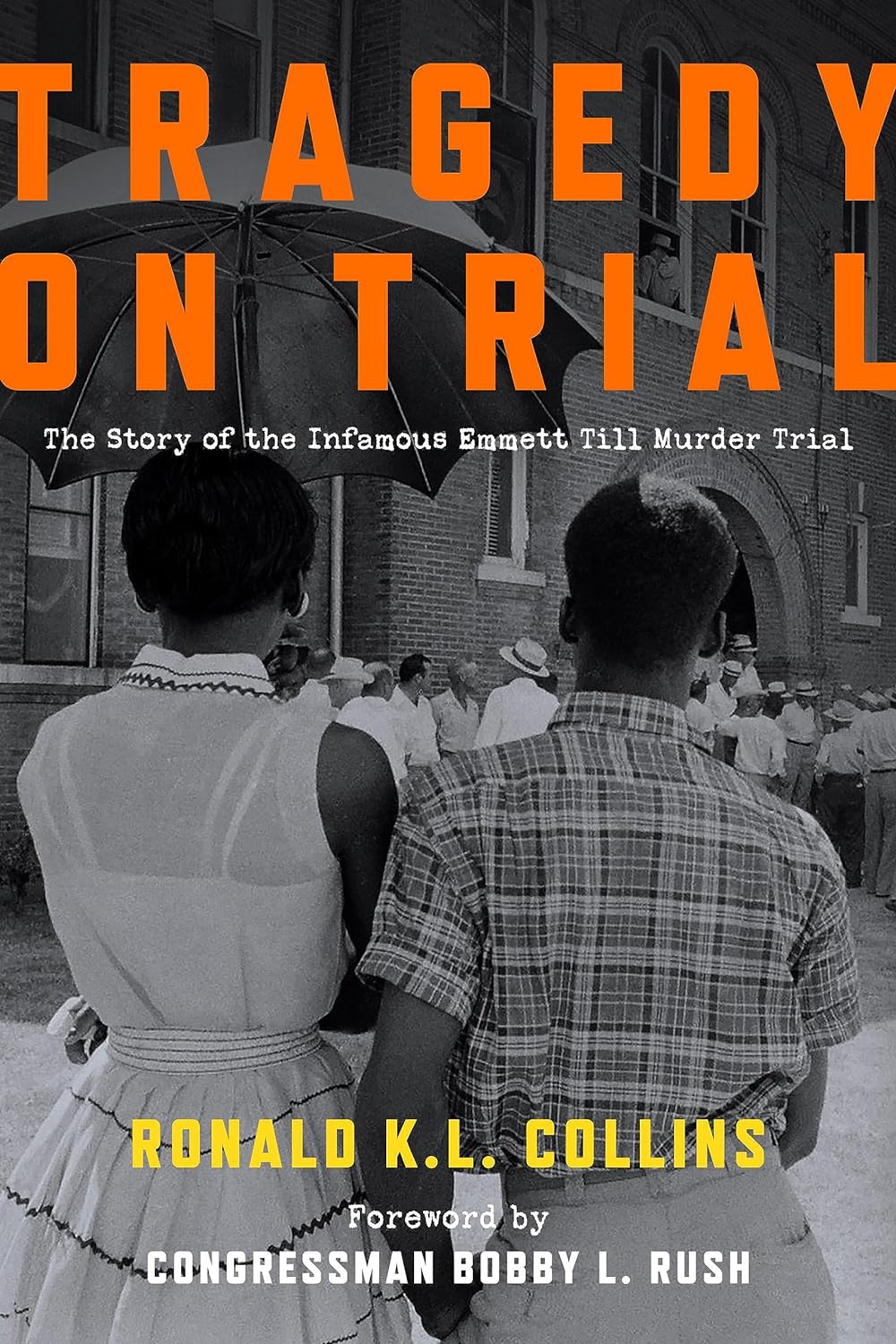

There’s something particularly compelling, though, in being able to read the long-unavailable criminal-trial transcripts in the case. They’re at the core of Professor Ronald K.L. Collins’ new book, Tragedy on Trial: The Story of the Infamous Emmett Till Murder Trial (Carolina Academic Press), which uses the testimony to give readers an illuminating understanding of the flow and drama of this historic trial.

Collins was a colleague of mine at the First Amendment Center for a number of years and I’ve long respected his work, including his pivotal book The Trials of Lenny Bruce: The Fall and Rise of an American Icon, written with David Skover. It also substantially drew on trial testimony.

The First Amendment Center was also where I had my first meaningful exposure to the Till story. In the late ‘90s, center founder John Seigenthaler brought Emmett’s mother Mamie Till-Mobley to Vanderbilt University for a program at our offices. There we heard firsthand about her determination to have the public see her son’s open casket in order to fully grasp this horrific crime. She spent decades helping to shine a light on racial injustice.

The crime has been well-documented. Emmett, a Chicago teen visiting his uncle, was abducted by white men, including Roy Bryant, husband of Carolyn Bryant, who had complained about Till’s conduct. Till’s disfigured body was found in the Tallahatchie River days later. Roy Bryant and his half-brother J.W. Milan were charged with murder.

After a brief trial and a 67-minute deliberation (including a soft-drink break), the all-white-male jury acquitted the defendants. Outrage over the verdict spread across the U.S. and Emmett’s murder became a touchstone of the civil rights movement.

Tragedy on Trial brings new dimensions to our collective understanding of the case. Among the takeaways:

- Although many tend to view the acquittal as inevitable, there was in fact a good-faith prosecution of the defendants. Prosecutors argued that the murder was premeditated, beginning with the defendants’ demand in the middle of the night that the young man be turned over to them. Once they had him in custody, the argument went, they had a duty not to harm him.

- District Attorney Gerald Chatham was credited with a powerful call for conviction.

- As Collins notes, James Hicks, a reporter for the black newspaper Cleveland Call and Post, observed that by “every courtroom standard, the Mississippi-born district attorney made a great case for the dead colored youth.”

- The defense lawyers largely maintained that there was no evidence linking their clients to the crime and that there was a question of whether the body found in the river was Till’s. Collins also shares the astonishingly cynical and racist arguments of defense lawyer John W. Whitten Jr., who suggested the entire case was in fact a conspiracy by outsiders.

- “This claim was yet another attempt to sway the jury that the real culprits in all of this were not the defendants, but a cadre of others hell bent on annihilating the southern way of life,” Collins writes.

- There was to be no justice for Emmett Till. After the trial, a grand jury was empaneled to consider kidnapping indictments, for which there was abundant evidence. After just about three hours, the grand jury declined to indict.

- After the trial, freelance reporter William Bradford Huie enticed Milan and Roy Bryant to admit to killing Till without specifically admitting guilt, which required paying a fee to the men and their law firm, as well as misleading manipulation of the narrative. That included the assertion that just the two men were involved, whereas evidence points to a larger pool of suspects. The widely read Look Magazine purchased and published Huie’s flawed story in 1956, and the article also reached millions in the pages of Reader’s Digest

In recent years, some state legislatures have engaged in heavy-handed tactics to discourage any classroom discussion of past and ongoing racial injustice. The argument is generally that we don’t want to make young white people feel uncomfortable about the actions of prior generations.

Collins’ revealing book offers a vibrant reminder that the racist murder of a 14-year-old in Mississippi just 69 years ago is undeniably relevant to 14-year-olds today. If it makes them uncomfortable that a great-grandfather may have had racist beliefs, so be it. If it makes them determined not to allow racial injustice in the future, even better.

Ken Paulson is the director of the Free Speech Center at Middle Tennessee State UniversityThe Free Speech Center newsletter offers a digest of First Amendment- and news media-related news every other week. Subscribe for free here: https://bit.ly/3kG9uiJ