Review of Laura Pappano, School Moms: Parent Activism, Partisan Politics, and the Battle for Public Education. Boston; Beacon Press, 2024.

It often takes years for legal issues raised by popular movements at the state and local level to reach the U.S. Supreme Court. Of all the issues currently surrounding the First Amendment, none is likely receiving greater local attention than the attempt to ban or remove certain books from both school and public libraries.

To date, Supreme Court precedents are rare. In upholding the right of students to wear black armbands in protest of the Vietnam War, the ruling in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969) established that neither students nor teachers shed their rights when they enter school classrooms.

In terms of actual book banning, the primary precedent is now more than 40 years old. In Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico (1982), the Supreme Court returned a case to lower courts to ascertain whether a school had improperly removed books from a school library on the basis that they were “anti-American, anti-Christian, Anti Sem[i]tic, and just plain filthy.”

Acknowledging the right of students to receive information, the Supreme Court decided that schools could not remove books (particularly those regarded as classics) because of the ideas they expressed (a form of content discrimination), while leaving room for administrators to decide on the appropriateness of materials that might be considered excessively explicit, vulgar or otherwise inappropriate for children.

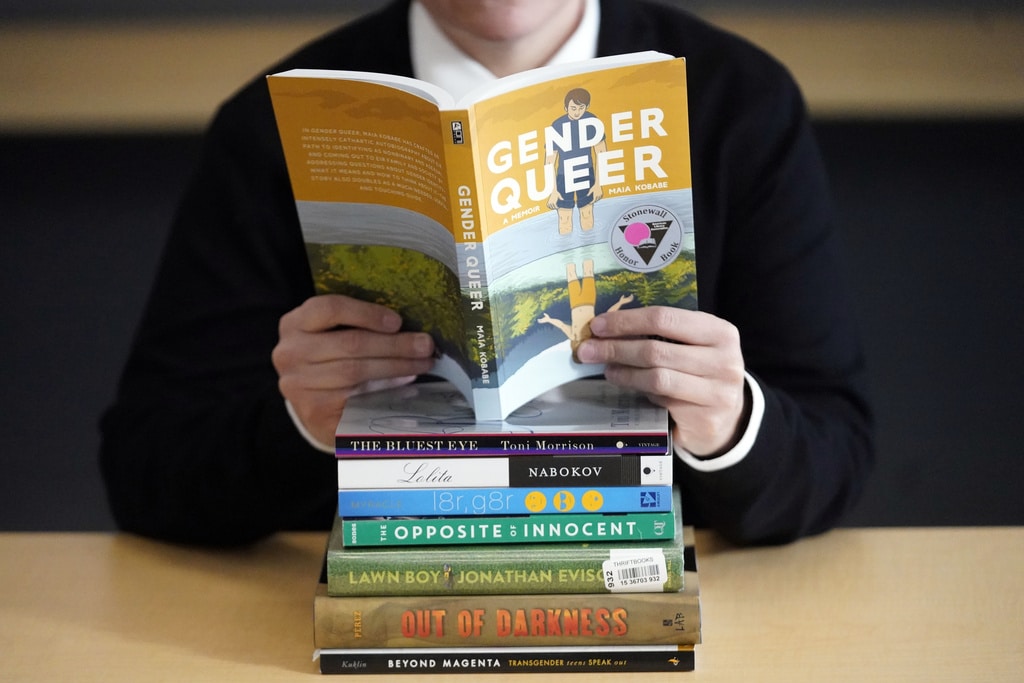

This still leaves considerable room for ambiguity and discretion, which has resulted in scores of book challenges in school and public libraries. The American Library Association reports that the number of attempted book bans rose from 273 recorded attempts in the U.S. in 2020 to 2,571 attempts in 2022 (Holton 2024, 203).

Current book censorship movement

Laura Pappano, a journalist who is proud of her own role as a school mom, traces the development of this book ban movement in “School Moms: Parent Activism, Partisan Politics, and the Battle for Public Education,” which recounts her own attempts to understand and to combat it. At a time when private and charter schools are capturing many of the headlines, Pappano is an unabashed proponent of the value of public schools and of wide access to a variety of library materials. She has attended conferences on the subject, interviewed scores of individuals on the front lines of controversy, and cites numerous examples of how issues of idea and book censorship have manifested themselves throughout the nation.

Pappano focuses on pressures from right-wing politicians and their followers, many of whom, taking their cues from Donald Trump, portray the current controversies in war-like terms. They have translated much of the public reaction against mask mandates during the COVID-19 pandemic into opposition to ideas, and expressions of ideas, that they believe undermine public morality and traditional understandings of American history and of family life.

Pappano observes that whereas parent-teacher associations used to be forums for communities to come together on behalf of educating children, they have increasingly become partisan battle grounds. She notes that Tennessee is one of a number of states in which school board members are now selected on a partisan rather than on a nonpartisan basis, often making it almost impossible for candidates to win election except by identification with a political party. She illustrates with the example of Nancy Garrett of Williamson County, Tennessee, who lost her seat on a school board after deciding to run as an unaffiliated candidate. Pappano notes that school board elections often draw relatively few participants many of whom are likely to be far more partisan than others within their parties.

Public school teachers and librarians are increasingly being attacked for choosing or retaining books that strike one or another political nerve. A host of vague state laws — often using the term “obscenity” in a broad, rather than in the technically legal sense identified in Miller v. California (1973) — and local ordinances now open teachers and librarians to the possibility of criminal prosecution for book selections, with teachers even being called into account for small libraries in their own classrooms. Much as in previous Red Scares, critics banty around terms like “groomers,” “pornographers,” “indoctrinators” and “Marxists” to describe those with more liberal views than their own. Teachers who were once praised for airing all sides of questions are now subject to termination for stirring up trouble.

Such movements have been particularly strong in Ron DeSantis’ Florida and in Greg Abbott’s Texas. They and other governors have crusaded against such ideas as:

- Social Emotional Learning, which emphasizes the social aspects of learning;

- Critical Race Theory (CRT), a movement identifying institutionalized forms of discrimination that critics have almost always mischaracterized and which has rarely, if ever, been a part of any elementary or secondary school curricula;

- wokeness, a form of political correctness, whose meaning is quite subjective;

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI), which is sometimes tied to the treatment of subjects like slavery or other issues that might make white students feel a sense of shame or guilt; and

- the treatment of LGBTQ+ issues — for example, Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” law — which Pappano believes can fuel disrespect for and prompt attacks upon such students.

The need for wider parental participation

The decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) led in many cases not so much to racial desegregation as to white flight into private schools. If public schools are to survive current partisan divisions, parents certainly need assurances that they retain some input into curricula to which their own children have access. However, many of the parents whom Pappano discusses want to impose their own narrow views of appropriateness on other people’s children, or even on public library patrons.

Although Pappano paints a relatively dismal picture of current battles over books—her description in Chapter 5 of the firing of Matthew Hawn from Sullivan Central High School in Tennessee for encouraging critical thinking among his students is particularly concerning. She knows from personal experience that individual parents can make a difference and believes that efforts to fight for public schools are worthwhile. Acknowledging that moms have not always been as effective in some areas (most notably racial justice) as in others, Pappano notes that even before they obtained the right to vote, women were often active in early school movements such as the National Congress of Mothers and Parent-Teacher Associations that brought about a variety of needed reforms.

She documents successful efforts to resist book bans and believes that the playing field would be much more equal if moms with more interest in their children than in one or another political ideology were to become more involved. An alternative that Pappano does not discuss at any length is that parents opposed to censorship might create their own schools, which would arguably exacerbate current cultural and partisan divisions further and remove more parents from public school debates.

Professor Wendell Bird has argued that whereas British laws relating to freedom of speech and press focused fairly narrowly on restrictions against licensing and prior restraint, those who formulated the First Amendment took a much wider view. Such broad freedoms are in jeopardy if self-appointed guardians are able to censure books available to citizens and students. The primary means for the censors to triumph is for those, including moms and dads of public school students, who oppose censorship to do nothing.

John R. Vile is a professor of political science at Middle Tennessee State University and the dean of the Honors College.