This week’s decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in Carson v. Makin, will encourage those who favor more public funding of religious schools, but it also illustrates the internal tension between two clauses of the First Amendment.

The First Amendment protects our freedom of religion in two ways. First of all, it bars the government from establishing religion. This means that government in the U.S. cannot favor one faith over another or fund religious activity. The second clause guarantees us the right to freely exercise our religion. Together these guarantees are designed to keep government as far away from religion as possible.

Those voting with the majority — Justices John Roberts, Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Brett Kavanaugh, Neil Gorsuch and Amy Comey Barrett — clearly sought to protect the free exercise of religion. In Maine, certain regions of the state have such a sparse population that they don’t have public schools. The state of Maine provides tuition funding for families that need to send their children to private schools instead. The law struck down by the Court bars the use of that tuition money in private religious schools.

“Saying that Maine offers a benefit limited to private secular education is just another way of saying that Maine does not extend tuition assistance payments to parents who choose to educate their children at religious schools,“ Chief Justice Roberts wrote in his majority opinion.

The state’s motivation for that exception was twofold. First, it did not want to fall afoul of the establishment clause by providing funds that would go to religious schools. Second, Maine was striving to provide a substitute for the civic education provided in public schools. The reasoning goes that some private schools can approximate that learning environment, but religious schools cannot.

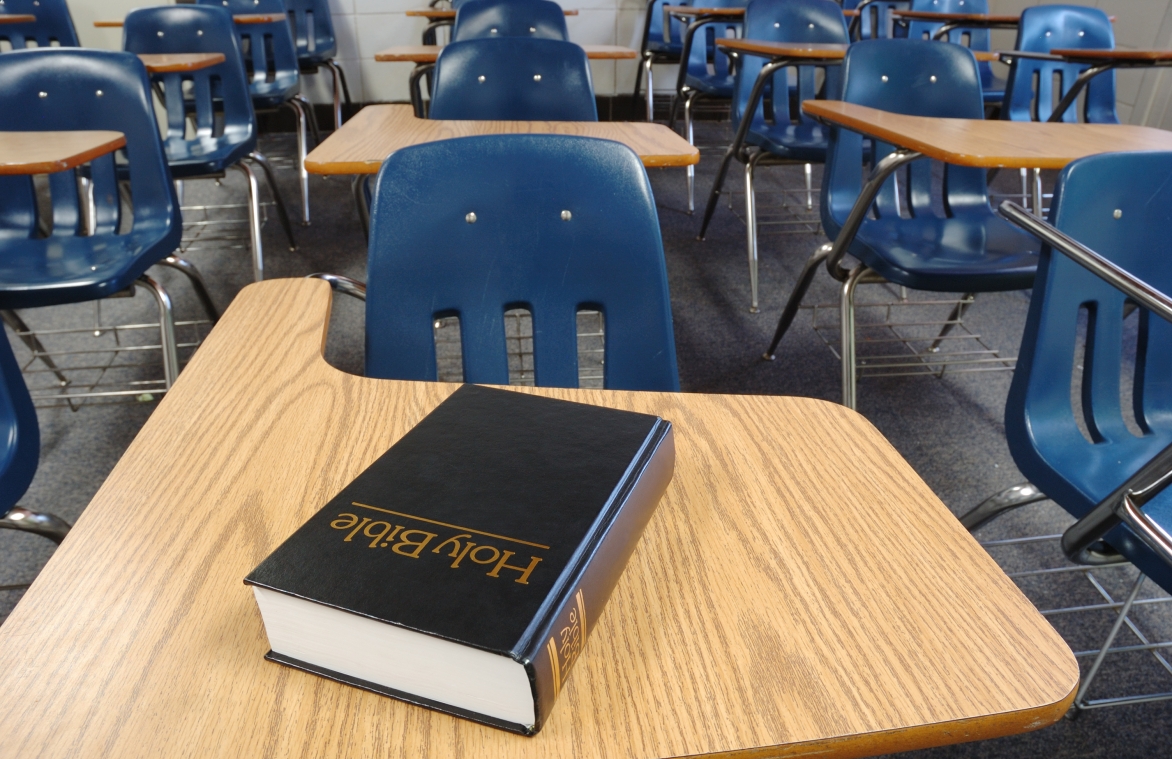

For example, the two plaintiffs noted that the curricula are deeply influenced by faith. Every subject is taught from a Christian perspective, and in at least one of the schools, the Bible is used in every classroom for every subject. This is a distinctly different educational experience from what traditional civic education provides.

This issue did not appear to trouble the majority, most of whom attended religious schools as children.

Roberts wrote that the Court’s decision was very much like that in Trinity Lutheran v. Comer, where the Court held that a state could not keep a religious school from receiving otherwise universally available school aid for the construction of playgrounds.

Dissenting Justice Stephen Breyer had another perspective. As he argued in his 18-page dissent, the majority didn’t acknowledge the importance of the establishment clause in this case. In Breyer’s view, though Maine could have included religious schools in its tuition program without violating the establishment clause, that doesn’t mean it should be required to do so.

Breyer’s distinction rests with using those funds for religious reasons. For example, playgrounds at a public school and religious school are going to be identical, bearing no relation to the schools’ respective missions. On the other hand, this Supreme Court ruling means that taxpayer money will go to teachers who are also essentially pastors sharing religious messages about the works of God while teaching geography and math. Under those circumstances, Breyer maintains, Maine’s exclusion of religious schools should have been upheld.

The Court’s decision does not mean that states now have to fund religious schools. It means that the states would be hard-pressed to bar benefits to religious schools that it is affording to other private schools.

The state also has some options. By redrafting the legislation to require the teaching of evolution along with other curricula, and requiring that participating schools not discriminate on the basis of faith, the state would likely deter most religious schools from participating.

It’s truly remarkable that the 45 words of the First Amendment have served this nation so well since 1791, but this case is a reminder that those core liberties can sometimes bump up against each other, and the pecking order of those freedoms will always be left to the judiciary. Perspectives change and so does the Court.

The Free Speech Center newsletter offers a digest of First Amendment and news media-related news every other week. Subscribe for free here: https://bit.ly/3kG9uiJ