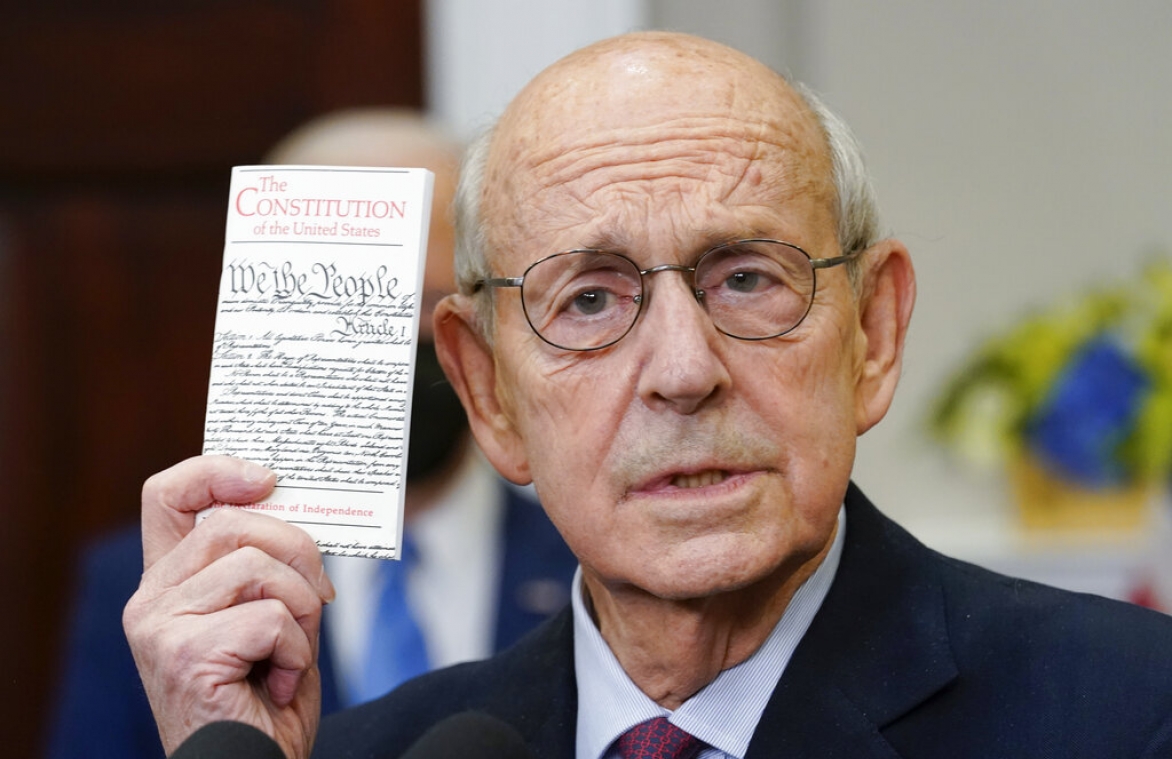

When it comes to the First Amendment, Associate Justice Stephen G. Breyer may have saved his best for last. Near the end of his judicial career he wrote the Supreme Court’s majority opinion in Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L. (2021), a student-speech case involving social media.

The case involved a disgruntled high school student upset over not making the varsity cheerleading squad. She posted a profanity-riddled, F-bomb tirade on SnapChat on a Saturday afternoon while hanging with a friend outside a convenience store.

The cheerleading coaches and school officials, less than pleased with the F-bombs, banned B.L. — now known as Brandi Levy — from the cheerleading squad for a year. She and her parents said school officials had exceeded their authority by punishing her for her off-campus, online speech.

Justice Breyer and nearly the rest of the Supreme Court — aside from Justice Clarence Thomas — agreed. Breyer identified three “features” of off-campus student social media expression that established that school officials should generally take a hands-off approach concerning student social speech delivered off school grounds.

Those three features: (1) school officials rarely act in loco parentis (as parents) when it comes to off-campus speech; (2) schools should not be in the business of regulating student speech 24 hours a day; and (3) schools have a duty to protect unpopular student speech, particularly when it takes place off campus.

Breyer did not articulate as clear a rule or standard as perhaps some would like. But his opinion was important for a couple of reasons. He emphasized key limitations on school authority. And he breathed life into the Supreme Court’s seminal student-speech case of more than 50 years ago — Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969).

Consider that since Tinker, the Supreme Court had several times retreated from the ideal of relatively free student speech. The Court created new rules or carve-outs from Tinker for vulgar and lewd speech in Bethel School District v. Fraser (1986); a reduced standard for so-called school-sponsored student speech in Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier (1988); and for speech that school officials reasonably believed advocated the illegal use of drugs in Morse v. Frederick (2007).

The student litigants in Fraser, Hazelwood, and Morse all lost, unlike John and Mary Beth Tinker before them. To student-speech advocates, a disturbing pattern had developed. And many thought this pattern would continue when the Court granted review in Brandi Levy’s case. But she prevailed, because Justice Breyer declared that the school was overreaching by punishing a student for off-campus social media speech that really was nothing more than a venting of frustration.

Breyer also delivered a line that student-speech advocates will cite for decades: “America’s public schools are the nurseries of democracy.”

The Free Speech Center newsletter offers a digest of First Amendment and news media-related news every other week. Subscribe for free here: https://bit.ly/3kG9uiJ

David L. Hudson Jr. is a professor at Belmont University College of Law who writes and speaks regularly on First Amendment issues. He is the author of Let the Students Speak: A History of the Fight for Free Expression in American Schools (Beacon Press, 2011), and of First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (2012). Hudson is also the author of a 12-part lecture series, Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (2018), and a 24-part lecture series, The American Constitution 101 (2019).