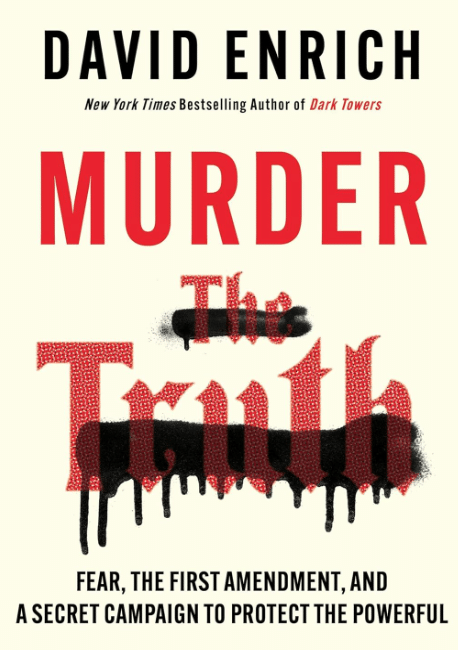

“Murder the Truth: Fear, the First Amendment, and a Secret Campaign to Protect the Powerful,” by David Enrich. New York: Mariner Books, 2025.

Reviewed by John R. Vile

One of the most important decisions of the Warren Court involving First Amendment freedoms of speech and press was its decision in New York Times v. Sullivan (1964). In that case, the court overturned an expensive libel judgment against The New York Times for a civil rights advertisement that the city commissioner of Montgomery, Alabama, demonstrated had contained some factual errors.

The Supreme Court had decided that public figures, especially elected officials, could only win such cases by showing “actual malice.” This, in turn, required proof that they had published the information knowing it to be false or with reckless disregard for its truth or falsity.

Critics of the Sullivan Decision

In recent years, President Donald J. Trump, who has called news media to account for publishing “fake news,” and who has labeled members of the press “enemies of the people,” has argued that this decision should be overturned.

Supreme Court justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch have also expressed their views that the decision should be reconsidered as when dissenting to a denial of a writ of certiorari in the case of Berisha v. Lawson (2021).Thomas expressed earlier concerns in McKee v. Cosby (2019). Former Circuit Judge Larry Silberman, who was prominent in conservative circles, was also a strident critic of the Sullivan decision.

Enrich explores threats to press freedom

David Enrich, a New York Times reporter who graduated from Claremont McKenna College and who has authored a number of other books including “Dark Towers” and “Servants of the Damned,” is a strong supporter of the Sullivan decision, but his book reveals that threats to First Amendment freedoms remain.

This is especially true when libel suits are launched from Great Britain, where the standards for proving libel are much lower, or in states that have not adopted anti-SLAPP laws. In such states, individuals with outside funding from deep-pocketed individuals or institutions who are less concerned with winning a libel judgment than in bankrupting news outlets, can still intimidate or bankrupt news media in a manner that chills free expression.

Enrich highlights many prominent libel cases since Sullivan. These include:

- The unsuccessful case brought by Saudi Arabian Prince Khalid bin Mahfouz against Rachael Ehrenfeld for her book “Funding Evil: How Terrorist Is Financed—and How to Stop It”;

- The large judgment won by Hulk Hogan against Gawker for violating his privacy by publishing a sex tape involving him;

- Bill Cosby’s unsuccessful libel suit against Katherine McKee for her allegations of rape;

- E. Jean Carroll’s judgement for defamation against President Trump after she accused him of the same;

- The successful suit against Rolling Stone for a shoddy story about an alleged rape at a University of Virginia fraternity;

- Businessman Eric Spofford’s unsuccessful case against a reporter who had questioned Granite Recovery Centers and his personal behavior;

- Dominion Voting System’s successful suit against Fox News for continuing to air false stories about its voting machines and the 2020 presidential election;

- Sarah Palin’s unsuccessful suit against the New York Times for a story written in haste and retracted that appeared to link her to a gun attack on members of Congress; and

- Lesser known cases, at the state and local level.

These cases show that while Sullivan has made it more difficult for public figures to prove libel, they can sometimes prevail when individuals make patently false accusations or journalists fail to exercise due diligence.

Too often, Enrich argues, those who lose such suits still manage to drive those who criticized them out of journalism through legal fees and the infliction of emotional stress. In some cases, reporters and their families have also been subject to physical harassment.

Enrich’s book will be of special interest to those who are interested in the lawyers on both sides of the libel issues. He devotes special attention to attorneys Tom Clare, Libby Locke and their former associates, and to Rodney Smolla, who has also weighed in on the subject as a scholar.

Enrich considers potential overturning of Sullivan case

Enrich believes that President Trump’s call “to open up our libel laws” has “rapidly metastasized into a [much larger] political and legal moment” (p. 266), the ultimate ramifications of which may not be known for some time. He opines that “Perhaps they will fail. Maybe they will only partially succeed. For instance, it is not hard to envision the Supreme Court substantially narrowing the scope of who classifies as a public figure or even ruling that the actual malice standard should only apply to government officials” (p. 267).

Even with the Sullivan opinion in place, Enrich is concerned about Trump’s continuing attacks on the press, and particularly about Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant’s suit against Mississippi Today demanding notes, internal communications and sources after it published stories about how the state had misspent federal grants designed to help the poor.

Enrich realizes that individuals like himself, who are employed by established news sources with good legal teams and relatively deep pockets, are in a privileged position and that local news sources, especially in states without anti-SLAPP suits (Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation), remain particularly vulnerable.

Original Intent and the First Amendment

Although most of the criticisms of the Sullivan decision have been based on the idea that the original intent of the American Founders with regard to First Amendment freedoms was relatively narrow, Wendell Bird has shown to this reviewer’s satisfaction, that the American view of the subject was much broader than the English view epitomized by William Blackstone (2020).

In a similar vein, Enrich points out that the conservative judge Robert Bork was among those who supported Sullivan. He observed in a concurring opinion in the D.C. Circuit Court decision Ollman v. Evans (1984) that libel actions “often seem as much designed to punish writers and publications as to recover damages for real injuries [and] may threaten the public and constitutional; interest in free, and frequently rough, discussion” (p. 35).

John R. Vile is a political science professor and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University.