By JESSICA GRESKO, Associated Press

WASHINGTON (AP) — Andy Warhol and Prince held center stage in a copyright case before the Supreme Court on Oct. 12 that veered from Cheerios and “Mona Lisa” analogies to Justice Clarence Thomas’ enthusiasm for the “Purple Rain” showman.

Despite the light nature of the arguments at times involving two deceased celebrities, the issue before the Court is a serious one for the art world: When should artists be paid for original work that is then transformed by others, such as a movie adaptation of a book?

The case affects artists, authors, filmmakers, museums and movie studios. Some amount of copying is acceptable under the law as “fair use,” while larger scale appropriation of a work constitutes copyright infringement.

As the 90-minute arguments unspooled, the justices discussed how courts should make that determination.

Justice Samuel Alito asked about a copy of the “Mona Lisa” in which the color of her dress was changed. Justice Amy Coney Barrett used “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy and its movie adaptation as an example, as well as a box of Cheerios cereal, making an analogy to famous Warhol images of Campbell’s Soup cans. The television shows “Happy Days” and “Mork & Mindy” were also cited.

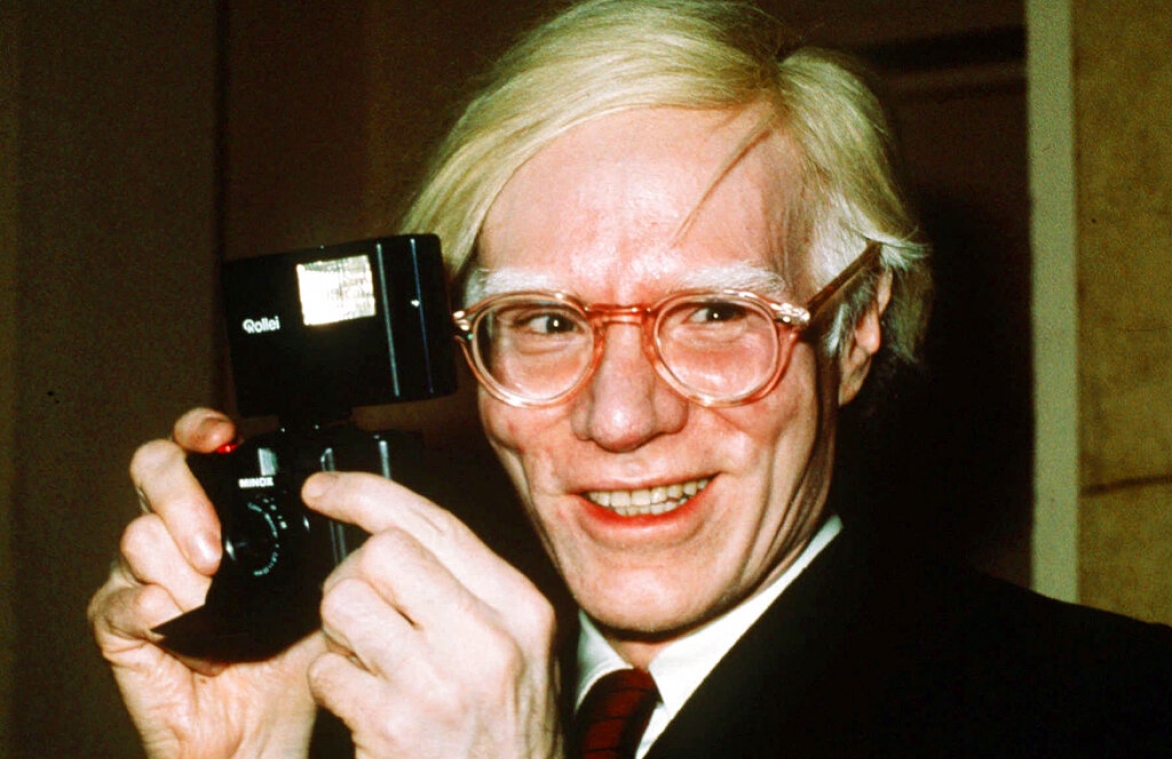

The case involves a portrait of Prince that Warhol created to accompany a 1984 Vanity Fair article on the music star. To assist Warhol, the magazine licensed a black-and-white photograph of Prince by Lynn Goldsmith, a well-known photographer of musicians, to serve as a reference. Goldsmith was paid $400.

Warhol used it to create portraits of Prince in the same style he had created well-known portraits of Marilyn Monroe, Jacqueline Kennedy and Mao Zedong. He cropped the image, resized it and changed the tones and lighting. Then he added his signature bright colors and hand-drawn outlines.

Warhol ultimately created several versions, including one of a purple-faced Prince that ran with the Vanity Fair story. Goldsmith got a small credit next to the image.

The issue in the case began when Prince died in 2016. Vanity Fair again featured another of Warhol’s Prince portraits, this time an orange-faced Prince that ran on the magazine’s cover. Warhol had died in 1987, but the magazine paid the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts $10,250 to use the portrait.

Goldsmith saw the magazine and contacted the foundation seeking compensation, among other things. The foundation then went to court seeking to have Warhol’s images declared as not infringing on Goldsmith’s copyright. A lower-court judge agreed with the foundation, but it lost on appeal.

Justice Thomas on Wednesday asked the foundation’s lawyer, Roman Martinez, whether the foundation would sue him for copyright infringement if he got creative with the Warhol image.

“Let’s say that I’m both a Prince fan, which I was in the ’80s,” he said, and a fan of Syracuse University, whose athletic teams are the Syracuse Orange. “And I decide to make one of those big blowup posters of Orange Prince and change the colors a little bit around the edges and put ‘Go Orange’ underneath.” Thomas said he would wave the poster around at games and would market it “to all my Syracuse buddies.”

Martinez implied he could sue and Thomas would lose.

A number of justices suggested that the appropriate result in the case is to clarify the first of four factors that courts use to assess whether something is “fair use” and to send the case back to lower courts for further review. “Why wouldn’t we send it back?” Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson asked at one point.

A range of high-profile organizations stressed the importance of the decision, including the Motion Picture Association, prominent museums in New York and Los Angeles, and the creators of “Sesame Street,” who say they often rely on “fair use” for parodies but also license copyrighted characters such as Cookie Monster and Elmo for use in new works by others.

Groups urging the justices to side with Goldsmith include the Biden administration, the organization that owns the copyrights to the works of Dr. Seuss, the Recording Industry Association of America and Jane Ginsburg, an intellectual-property expert and daughter of the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The Warhol foundation’s supporters include the foundations of two other prominent artists, Robert Rauschenberg and Roy Lichtenstein.

A decision in the case, The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts v. Lynn Goldsmith, 21-869, is expected by the end of June when the Supreme Court typically breaks for its summer recess.

The Free Speech Center newsletter offers a digest of First Amendment and news media-related news every other week. Subscribe for free here: https://bit.ly/3kG9uiJ