The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Packingham v. North Carolina (2017) invalidating a North Carolina law broadly limiting the ability of former sex offenders from accessing various material on the Internet has caused other courts to invalidate laws that impose myriad restrictions on sex offenders.

For example, a federal district court judge in Kentucky invalidated a Kentucky law that was arguably even broader than the North Carolina law invalidated in Packingham. But, Packingham is not a cudgel that can fell all laws restricting the rights of those classified as sex offenders.

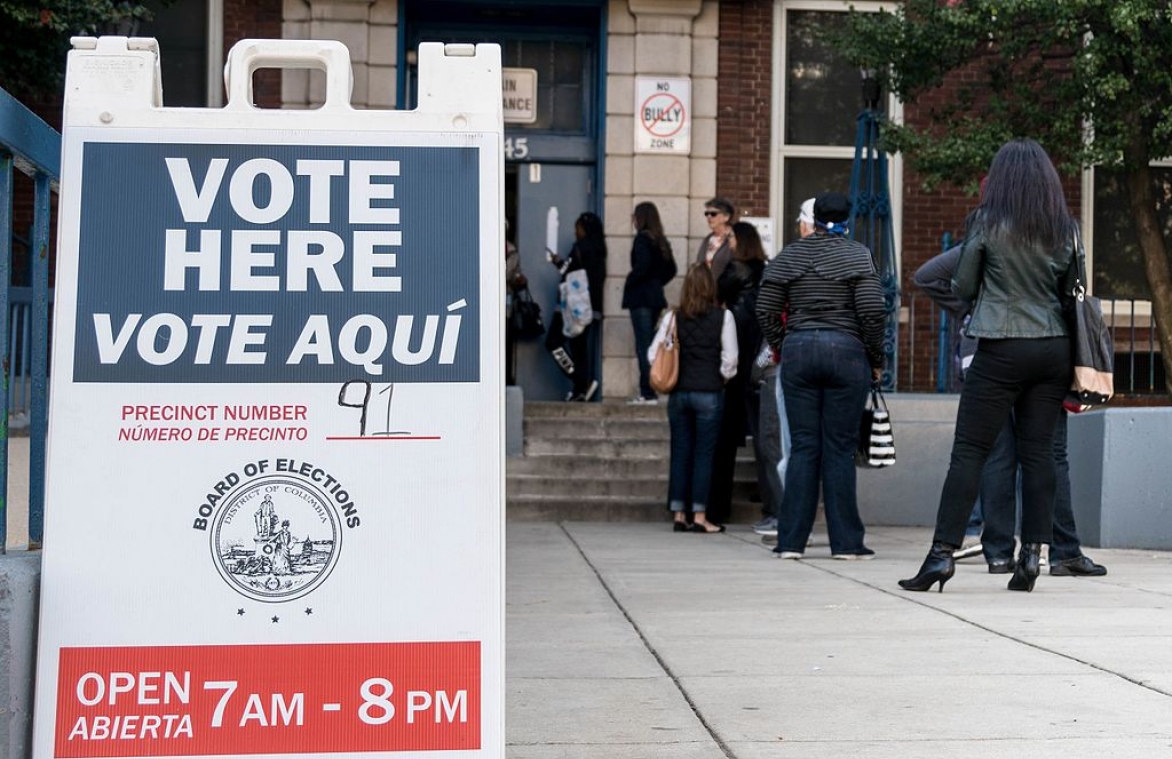

Case in point – the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rejected the constitutional challenge of an Indiana man who challenged a state law that prohibited him from voting in a public school. The man had been convicted of a sex offense involving a child years ago in California and later moved to Indiana.

Indiana has a law that prohibits “serious sex offenders” from knowingly or intentionally entering school property. This posed a problem for the man, because his neighborhood polling place was at a nearby school very close to his residence.

He argued that the Indiana law violated his right to vote under the First and Fourteenth Amendments. The state countered that the law served the state’s interests in preventing sex offenders from being near areas populated by children.

The 7th Circuit sided with the state in Valenti v. Lawson. The appeals court noted that the Indiana law was much different than the broad North Carolina law invalidated in Packingham. “The Indiana statute narrowly bans serious sex offenders from entering school property, a place where they could come into direct physical contact with children,” the appeals court wrote.

The 7th Circuit also noted that there were alternative methods for the man to vote, including voting at the county courthouse a day before the election, at a civic center 12 miles from his home, or by absentee ballot.

The man argued that these alternative methods deprived him of his right to associate and express himself with his neighbors at or near the polling place closest to his home. The 7th Circuit was not persuaded: “[the man’s] arguments are not even remotely persuasive given the ample alternatives that Indiana provides to him, especially considering the state is not required to offer any alternatives at all.”