Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), a radical youth group established in the United States in 1959, developed as a branch of an older socialist educational organization, the League for Industrial Democracy.

The SDS held a passionate, if somewhat naive, belief that a nonviolent youth movement could transform U.S. society into a model political system in which the people, rather than just the social elite, would control social policy. The civil activism of its members frequently led them to exercise their First Amendment freedoms, sometimes in conflict with government officials.

First members of SDS were ‘red-diaper babies’

The first members of SDS were mostly “red-diaper babies” — that is, the children of parents who were themselves politically active and who had participated in progressive, and radical, social movements in the 1930s.

The newly formed SDS held its first organizational meeting in 1960 in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where Robert Alan Haber was elected president.

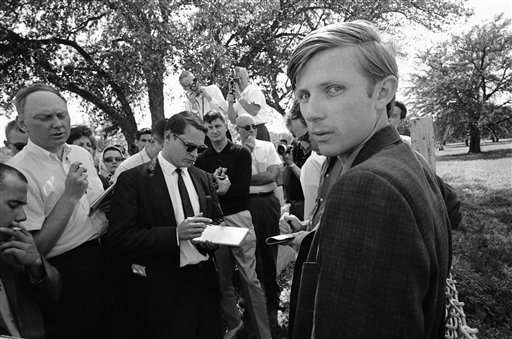

Tom Hayden, founder of the Students for a Democratic Society, testifies before the President’s Commission on Violence in 1968. (AP photo)

SDS manifesto criticized US political system

The political manifesto of the SDS, the Port Huron Statement, was written primarily by Tom Hayden, the 22-year-old former editor of the student newspaper at the University of Michigan.

The document, adopted in 1962 by the founding members of SDS, criticized the U.S. political system for failing to achieve international peace or to address effectively a myriad of social ills, including racism, materialism, militarism, poverty, and exploitation.

The manifesto called for a fully “participatory democracy” that would empower citizens to share in the social decisions that directly affected their lives and well-being.

SDS led to political awakening, protests on college campuses

The civil rights movement that led to the formation of the SDS also precipitated another politicized youth movement, the Berkeley Free Speech Movement (FSM), led by junior philosophy major Mario Savio.

The Free Speech Movement arose as a First Amendment protest against the actions of University of California Berkeley officials, who were under pressure from prominent community leaders to prevent students from collecting donations and recruiting other students for work in the civil rights movement in the segregated South.

Together, the two movements — SDS and FSM — generated a political awakening across college campuses that was dubbed the New Left and became the core of the counterculture movements that dominated student activism during the sixties.

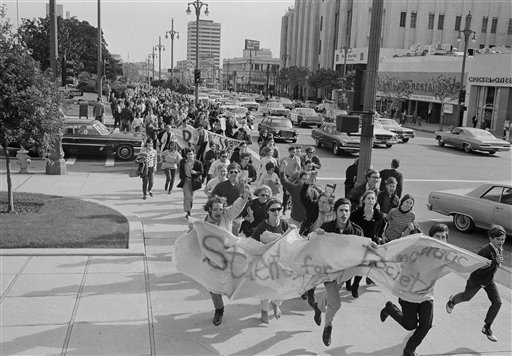

In this photo, several hundred people affiliated with the SDS race through the Los Angeles Civic Center en route from the Federal Building to the County Courthouse in a demonstration against the Vietnam War in 1968. (AP Photo/Harold Filan, used with permission from the Associated Press)

SDS slogans like ‘Make love – not war’ become anti-war rallying cries

Shortly, however, the Vietnam War changed the direction of student activism. It quickly gravitated to the anti-war movement when in January 1966 the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson announced it would abolish automatic student deferments from the draft.

The SDS slogans of “Make love — not war,” “Burn cards, not people,” and “Hell, no, we won’t go!” became the rallying cries for the anti-war movement.

SDS membership dwindled after FBI scrutiny

Meanwhile, the SDS began to fall victim to internal factionalism and its own democratic processes.

As its membership became more diverse, various factions became intolerant of each other and vied for leadership and control of the SDS political agenda.

Followers of hard-line philosophies, such as those of Che Guevara and Mao Zedong, as well as that of the radical Weathermen Underground or Weathermen, became the subjects of investigations by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) for terrorist activities. The FBI scrutiny, along with the end of the Vietnam War, saw the national SDS organization diminish rapidly and its membership drift away sufficiently so that by the mid-1970s the SDS was effectively dead.

This article was originally published in 2009. William W. Riggs was a Professor at Texas A&M International University.