Today it is taken for granted that the U.S. Supreme Court will apply the guarantees of the First Amendment and other provisions within the federal Bill of Rights to the states via the due process clause of the 14th Amendment (1868), but this development did not occur until the 20th century.

Moreover, even then, early decisions continued to recognize classic exceptions to First Amendment protections such as obscenity, blasphemy, libel, sedition and other speech deemed deleterious to public morals or welfare.

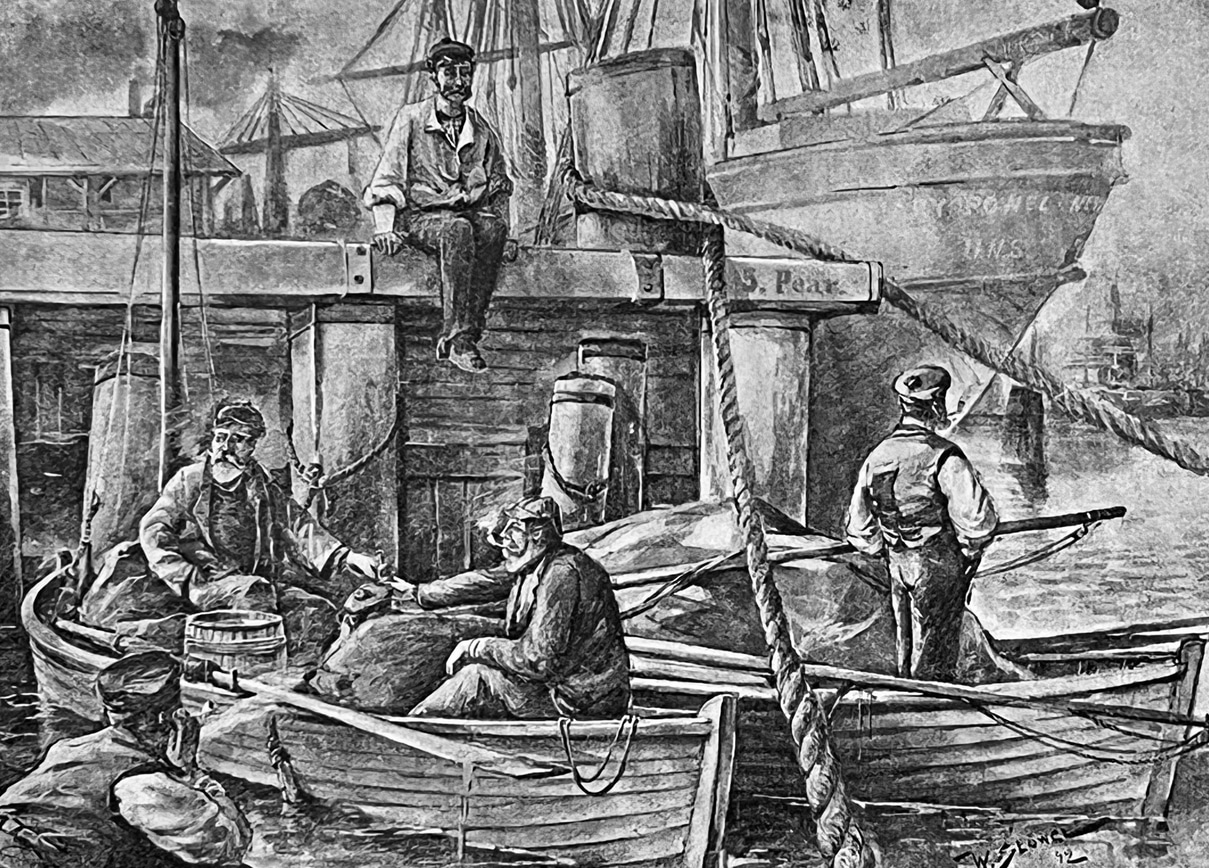

Although the case of Robertson v. Baldwin does not directly deal with the First Amendment, the majority opinion written by Justice Henry Billings Brown expressed the court’s attitude on the subject at the time. At issue was a federal law that allowed governmental officials to return to their ships seamen who had deserted their posts before their contracts expired . The question was whether the law violated the prohibition in the 13th Amendment (1865) against “involuntary servitude.”

Case reflects Supreme Court's view of Bill of Rights

The court majority pointed to a host of similar laws, dating back to ancient Greek history and continuing through British history and colonial times, which had upheld such laws. They had done so on the basis that sailors, even those like the men in this case who were working for civilian employers, were — much like members of the military — in a special category of individuals over which the state could exercise control lest the ships in service of which they had contracted be left without a crew.

In arguing that the 13th Amendment did not change this, Justice Brown cited the federal Bill of Rights. He observed that:

The law is perfectly well settled that the first ten amendments to the Constitution, commonly known as the “Bill of Rights,” were not intended to lay down any novel principles of government, but simply to embody certain guaranties and immunities which we had inherited from our English ancestors, and which had, from time immemorial, been subject to certain recognized exceptions arising from the necessities of the case. In incorporating these principles into the fundamental law, there was no intention of disregarding the exceptions, which continued to be recognized as if they had been formally expressed. Thus, the freedom of speech and of the press (Art. I) does not permit the publication of libels, blasphemous or indecent articles, or other publications injurious to public morals or private reputation.

Brown continued to cite other provisions within the Bill of Rights to illustrate the same point. In his view, these amendments embodied principles of English common law such as those articulated by William Blackstone rather than establishing significantly wider protections.

Justice John Marshall Harlan I wrote a strong dissent arguing that sailors should not be treated like children or wards of the state who were exempt from the 13th Amendment, but his opinion in this case did not specifically differ from Brown’s decision with respect to the meaning of the First Amendment.

John R. Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University.