The Supreme Court decision in Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. Federal Communications Commission, 395 U.S. 367 (1969), was a victory for those who believe that government ought to take steps to ensure that radio and television provide the public with a significant amount of information on public issues so that its members can make rational political decisions. Others contend the decision infringed on the First Amendment rights of broadcasters to exercise editorial discretion unimpeded with governmental mandates and air controversial material at their choosing.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC), one of whose functions is to grant licenses to radio stations and to television stations that transmit their programs via the airwaves, has developed what is known as the “fairness doctrine,” requiring that its broadcast licensees devote some time to discussing public issues and give each side of these issues fair coverage.

Journalist asked for radio time under fairness doctrine

The Red Lion Broadcasting Company was the owner of a right-wing radio station in Pennsylvania.

One of its broadcasters, Reverend Billy James Hargis, denounced a journalist named Fred Cook, who had written a book attacking conservative Republican Arizona senator Barry Goldwater.

Hargis’s bitter lashing of Cook included comments that Cook was once fired by a newspaper for making false charges about city officials and that he had once worked for a publication affiliated with the Communist Party. Cook, citing the fairness doctrine, demanded that he be given free time on the station to respond to Hargis’s charges.

The FCC, over Red Lion’s objections, agreed with him.

Supreme Court upheld FCC rules requiring station to air rebuttal

On appeal the Supreme Court, in a unanimous 8-0 decision by Justice Byron R. White (Justice William O. Douglas did not participate), upheld the FCC decision.

The Court also upheld a rule adopted after the Red Lion litigation was begun stating that the fairness doctrine required that a licensee give a person whose character was attacked in one of its broadcasts a reasonable opportunity to respond using the licensee’s facilities.

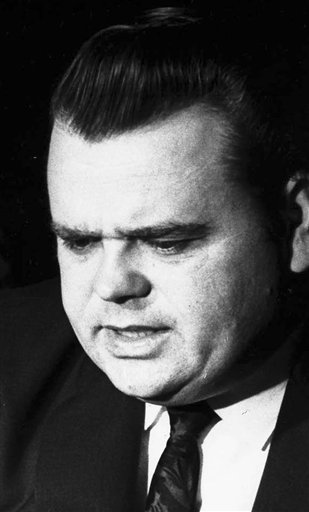

Photo of Fred J. Cook, from the back cover of one of his books. Cook was a journalist and author who wrote a book attacking Sen. Barry Goldwater. Radio personality Billy James Hargis attacked Cook on air, and Cook, citing the fairness doctrine, demanded that he be given free time to respond. The FCC agreed and the regulation was upheld by the Supreme Court in Red Lion Broadcasting v. FCC (1969).

Court said fairness doctrine did not violate First Amendment

After determining that the specific fairness-doctrine–based order to Red Lion Broadcasting and the new rule were justified by the relevant federal legislation, White turned to the question of whether they violated the First Amendment.

He declared that they did not. He pointed out that the airwaves are a scarce resource and that the spectrum would be overcrowded if everyone who wished to have a radio station were given a license to operate one. The resulting scarcity of stations creates the danger that some points of view might never be aired. Consequently, the licensees cannot be said to have a constitutional right to monopolize their frequencies and, in fact, the government, despite the First Amendment, could have divided up a given frequency among the various groups and individuals who wished to use it, each being allocated a specific portion of the broadcast day or week. This would make it certain that the broadcast media would furnish the public with diverse ideas and information.

Court cited need to preserve marketplace of ideas in justifying FCC regulation

The order to Red Lion giving Cook time to respond and the rule specifying that individuals personally attacked on a station be given an opportunity on that station to rebut the charge are simply less-far-reaching ways of achieving this goal. In determining whether governmental regulation of broadcasting violates the First Amendment, White said, “It is the right of the viewers and listeners, not the right of the broadcasters, which is paramount. … It is the purpose of the First Amendment to preserve an uninhibited market-place of ideas in which truth will ultimately prevail, rather than to countenance monopolization of that market.”

Red Lion did not explicitly uphold the fairness doctrine generally against constitutional attack, but it was reasonably assumed in Federal Communications Commission v. League of Women Voters of California (1984) that it had done so.

Critics have said scarcity of airwaves argument was outdated with cable TV expansion

Critics thought that Red Lion discouraged the broadcasting of controversial matter and that it is out of date, as the development of cable television has made the scarcity of airwaves much less significant now.

Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo (1974) refused to extend the holding to the print media.

Court continues to say rights of listeners prevail over rights of broadcasters

The fairness doctrine itself was scrapped in 1987. Yet Red Lion has never been overruled, and at times the Supreme Court reiterates its thesis that the rights of the listeners to information should prevail over those of the broadcasters.

For example, in CBS, Inc. v. Federal Communications Commission (1981), Chief Justice Warren Burger’s majority opinion actually italicized Red Lion’s language asserting this view.

And Justice Anthony Kennedy’s opinion in Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. v. Federal Communications Commission (1994), which refused to overturn a federal law requiring that cable systems carry a certain number of stations transmitting signals through the air, also articulated this philosophy (without actually citing Red Lion) when it declared that one of the reasons the statute was passed was to ensure “that the public has access to a multiplicity of information sources.”

This article was originally published in 2009. Daniel C. Kramer (1934-2010) was the author of six books and numerous articles about public law and American politics. He was a professor at the College of Staten Island for over 30 years before becoming a professor emeritus in political science.