Like public radio, American public television is premised on the idea that stations should be independently owned and operated to further the full exercise of First Amendment freedoms.

This idea led to the passage of the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967, creating the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, a private nonprofit corporation funded by taxpayers to distribute grants to public radio and television stations throughout the country.

Upon the signing of the act, President Lyndon B. Johnson said, “At its best, public television would help make our nation a replica of the old Greek marketplace, where public affairs took place in view of all the citizens. But in weak or even in irresponsible hands, it could generate controversy without understanding; it could mislead as well as teach.”

The Corporation for Public Broadcasting had lasted for 58 years when it announced on Jan. 5, 2026, that its board had voted to dissolve after it disbursed its remaining grant funds. The vote to end the organization came after Congress voted to claw back $1.1 billion of its funds and after President Donald Trump had pushed to end the corporation's work through an executive order titled "Ending Taxpayer Subsidization of Biased Media.”

Trump had argued that the media landscape had changed significantly since 1967. and that "today the media landscape is filled with abundant, diverse, and innovating news options.” Under such circumstances, continued governmental funding “is not only outdated and unnecessary but corrosive to the appearance of journalistic independence,” the order said.

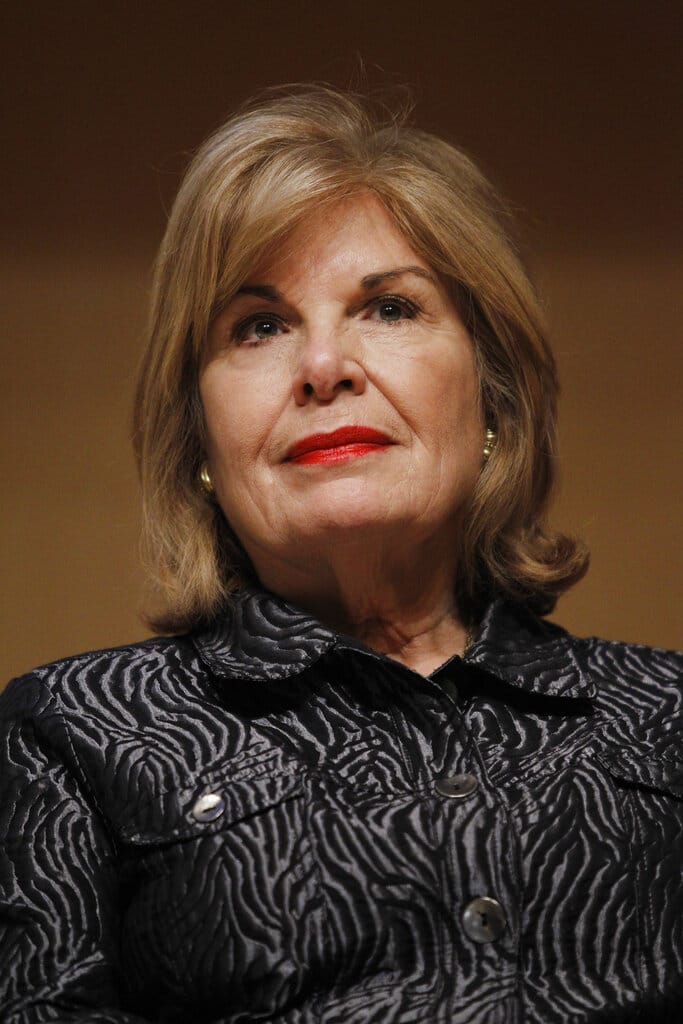

Patricia Harrison, the corporation's president and CEO, said in a press release announcing the dissolution said: “When the Administration and Congress rescinded federal funding, our Board faced a profound responsibility: CPB’s final act would be to protect the integrity of the public media system and the democratic values by dissolving, rather than allowing the organization to remain defunded and vulnerable to additional attacks.”

It's not yet entirely clear the effect of eliminating the grant funding to public television and radio stations throughout the country. Many of the stations in larger urban areas also have significant private contributions. But those smaller stations in less populated areas may bear a larger brunt of the loss of funds.

Public television has been a target of criticism

Programming on public television has been a target of criticism since the inception of the Corporation of Public Broadcasting.

Bill Moyers, a former assistant to President Johnson and a veteran of public television, said the Corporation for Public Broadcasting was established “to set broad policy for public broadcasting and to be a firewall betweeen political influence and program content.”

But recurring threats of reduced federal funding and allegations of editorial bias threatened that firewall from the beginning.

Early on, such edgy programs such as "The Great American Dream Machine," a satirical magazine series, and "VD Blues," a frank look at venereal disease in an era when the subject was usually discussed only in doctors’ offices, angered White House operatives who thought public television had gone too far.

In 1972 President Richard M. Nixon vetoed a two-year funding measure for public television and radio. In protest, CPB president and former Republican representative Thomas Curtis and several board members resigned. Nixon then appointed board members who directed monies to high-culture, politically uncontroversial programs.

Ironically, public television’s gavel-to-gavel coverage of the Senate and House committee hearings into the Watergate scandal that led to Nixon’s 1974 resignation galvanized the viewing audience and its commitment commitment to programming was rejuvenated.

Patricia Harrison, president of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, is seen Friday, March 25, 2011, at the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia. In January 2026, Harrison announced the corporation was dissolving after Congress had rescinded its funding. The corporation gave grants to public broadcasting stations for more than 58 years. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Court weighed in on public television’s First Amendment rights

The Supreme Court weighed in on public television’s right to freedom of expression in its 1984 decision in Federal Communications Commission v. League of Women Voters of California. The league joined with Pacifica Corporation, which owned several public television stations, and Rep. Henry Waxman, D-Calif., in challenging section 399 of the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967. The section prohibited “editorializing” by any noncommercial broadcaster receiving money from CPB. The high court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs. Writing for the majority, Justice William J. Brennan Jr. stated that section 399 was unconstitutional because it “directly prohibits the broadcaster from speaking out on public issues even in a balanced and fair manner.”

Another major battle over programming content emerged after CPB chair Kenneth W. Tomlinson hired former Republican National Committee co-chair Patricia Harrison as president and chief executive officer.

Harrison was asked to assess the degree of what Tomlinson considered “liberal bias” in noncommercial television. He took particular aim at NOW, a one-hour news program hosted by Moyers. Tomlinson also oversaw the creation of The Journal Editorial Report, a program underwritten by the Wall Street Journal, to provide what he considered to be conservative balance.

An investigation by CPB inspector general Kenneth Konz found that Tomlinson “violated statutory provisions” and the CPB board code of ethics by negotiating directly with programmers in creating Journal. Konz reported that e-mails between Tomlinson and White House staffers made it appear that Tomlinson “was strongly motivated by political considerations in filling the President/CEO position.”

In 2006 Public Broadcasting System President Paula Kerger took the federal government to task for what she called its paralyzing effect on public television stations. At a meeting of the Television Critics Association, Kerger accused the FCC of using unclear rules for enforcing decency standards to impose fines that could put stations out of business. To stave off anticipated FCC fines in 2007, PBS distributed two different versions of Ken Burns’s World War II documentary The War, with one version sanitized of several expletives. Here, Burns gives a keynote speech on June 7, 1999, at Public Broadcasting System’s annual meeting. (AP Photo/Ben Margot)

PBS and FCC involved in indecency controversy over profanity

In 2006 the president of Public Broadcasting System, which distributes educational programming and received funding from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, took the federal government to task for what she called its “paralyzing” effect on public television stations. At a meeting of the Television Critics Association, the PBS president, Paula Kerger, accused the FCC of using unclear rules for enforcing decency standards to impose fines that could put stations out of business.

As an example, Kerger cited a $15,000 fine against KCSM-TV of San Mateo, California, for a 2004 airing of an episode of "The Blues," a music documentary by director Martin Scorsese. The program contained interviews in which profanity was uttered that the FCC deemed unnecessary.

To stave off anticipated FCC fines in 2007, PBS distributed two different versions of Ken Burns’ World War II documentary "The War." One version had been sanitized of several expletives, a move which a New York Times editorial described as “a troubling white washing of the nature of war.”

In March 2008, the Supreme Court agreed to examine the FCC’s “fleeting expletives” rules in Federal Communications Commission v. Fox Television Stations after the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals struck the rules down in June 2007. Under the fleeting expletive policy as interpreted by the FCC, a single curse word could cross the line into proscribable indecency. Critics contend this conflicts with the FCC’s earlier, more lenient policy. The circuit court found that the FCC’s rationale of defending community standards was “divorced from reality” and that the rules probably violated the First Amendment.

Trump’s executive order attempting to withdraw funding

On May 1, 2025, President Trump issued his executive order to eliminate funding. Arguing that “Americans have the right to expect that if their tax dollars fund public broadcasting at all, they fund only fair, accurate, unbiased, and nonpartisan news coverage,” Trump argued, without providing any examples that neither National Public Radio nor Public Broadcasting System present “a fair, accurate, or unbiased portrayal of current events to taxpaying citizens.”

Essentially equating speech on public media to government speech, Trump observed that “the Government is entitled to determine which categories of activities to subsidize.” He ordered the cessation of any direct or indirect funding of public broadcast entities. He further ordered that the Corporation for Public Broadcasting should determine whether the entities had subjected their employees to discrimination “on the grounds of race, color, religion, national origin, or sex.”

Trump’s order was complicated by the fact that Congress allocated funding two years in advance for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting to protect it from partisan pressures (Nauman 2025). And although public television stations receive CPB funding, many in larger urban areas are also funded by large private contributions.

This article was originally published in 2009. Gina Logue is a 20-year radio journalism veteran who has covered events ranging from presidential elections to the 1996 Summer Olympics. Since 2001, she has worked in the Office of News and Media Relations at MTSU and has won over 20 awards for her work there.