In Parker v. Levy, 417 U.S. 733 (1974), the Supreme Court established for the first time the limits of free political expression for those serving in the armed forces of the United States. The Court determined that the demands of military necessity are superior to individual constitutional rights in the military setting.

Judicial decisions have privileged military interest over individual rights

The U.S. Court of Military Appeals held in United States v. Jacoby (1960) that “the protections of the Bill of Rights, except those which are expressly or by necessary implication inapplicable, are available to members of our armed forces.” Military and civilian courts alike balance the interest in military necessity against the right of service personnel to exercise First Amendment rights. Beginning with Levy, the landmark case regarding First Amendment rights in the military, judicial decisions have privileged the military interest.

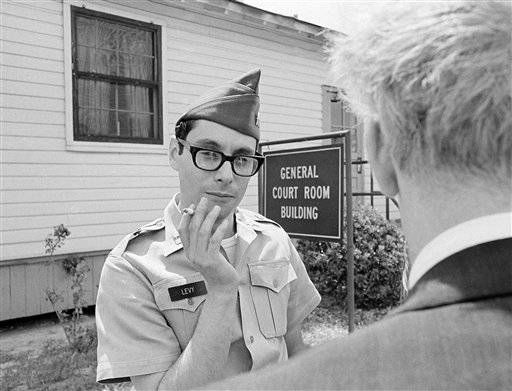

Army captain court-martialed for making disloyal statements

Dr. Howard Levy, an Army captain stationed at a U.S. Army hospital in South Carolina, urged black enlisted men to refuse to serve in Vietnam because “they are discriminated against and denied their freedom in the United States, and . . . discriminated against in Vietnam by being given all the hazardous duty and they are suffering the majority of casualties.” He also claimed that “Special Forces personnel are liars and thieves and killers of peasants and murderers of women and children.”

Levy was court-martialed and convicted under Articles 133 and 134 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) for “conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman” and disloyal statements prejudicial to “good order and discipline.” The federal district court affirmed; however, the court of appeals reversed on the ground that the Articles were unconstitutionally vague. In a 5-3 decision, the Supreme Court reinstated Levy’s conviction.

Court reinstated the conviction

Justice William H. Rehnquist, writing for the Court majority, recognized that service personnel possess constitutional rights but noted that the “fundamental necessity for obedience, and . . . the imposition of discipline” might require greater limitations of First Amendment rights than are tolerable within civilian life. These necessities arise from the fact that the military is “a specialized society separate from civilian society,” ready to fight wars and to act without question in response to orders. Consequently, the Court rejected claims of vagueness regarding the UCMJ, claiming that prior constructions of the Articles in question narrowed the scope of their application. The Court also denied to service personnel the right to challenge the Articles for overbreadth.

Dissenters thought majority gave too much deference to military

Justice William O. Douglas dissented, reasoning that the majority had given too much deference to military officials. “Uttering one’s belief is sacrosanct under the First Amendment,” he wrote. Justice Potter Stewart — joined by Justices Douglas and William J. Brennan Jr. — also wrote a dissenting opinion. He contended that the rules of military justice under which Dr. Levy was charged were unconstitutionally vague.

Levy has served as precedent for subsequent decisions allowing military prosecution for such disparate offenses as possessing marijuana off base (Schlesinger v. Councilman [1975]), exercising the right to petition without permission from the base commander (Brown v. Glines [1980]), and wearing religious garb in violation of the uniform dress code (Goldman v. Weinberger [1986]). It remains the foundation for judicial recognition of “military necessity” as a weightier interest than First Amendment rights of individuals in the military.

This article was originally published in 2009. Richard A. “Tony” Parker is an Emeritus Professor of Speech Communication at Northern Arizona University. He is the editor of Speech on Trial: Communication Perspectives On Landmark Supreme Court Decisions which received the Franklyn S. Haiman Award for Distinguished Scholarship in Freedom of Expression from the National Communication Association in 1994.