Panhandling is a form of solicitation or begging derived from the impression created by someone holding out his hand to beg or using a container to collect money. When municipalities regulate panhandling — a form of speech — First Amendment rights become an issue. Supporters of panhandling regulation contend it is a safety measure designed to protect people from harassment and other crimes. Opponents of such regulation contend it is blatant suppression of the First Amendment rights of the poor and dispossessed.

Passive versus aggressive panhandling

There are two types of panhandling: passive and aggressive. Passive panhandling is soliciting without threat or menace, often without exchanging any words at all — just a cup or a hand is held out. Aggressive panhandling is soliciting coercively, with actual or implied threats, or menacing actions. If a panhandler uses physical force or extremely aggressive actions, the panhandling may constitute robbery.

U.S. cities have restricted panhandling

In recent years, an increasing number of U.S. cities have enacted ordinances restricting panhandling because of the influx of people living in public spaces. For the most part, cities are particularly concerned about the effects of panhandling on public safety, tourism and small businesses.

So far, this trend has included measures making it illegal for persons to ask for money in public, as well as measures prohibiting activities such as sleeping/camping, eating, sitting, and begging in public spaces. Other efforts to crack down on panhandling and related activities include limiting begging to daylight hours, barring panhandling from certain areas, banning panhandlers on drugs or alcohol, ticketing or fining panhandlers, and imposing license requirements.

The growing number of ordinances criminalizing panhandling over the years has spun off a corresponding growth in support of panhandlers’ free speech rights under the First Amendment. Although the Supreme Court has never addressed this issue directly, its decisions provide some guidance to regulations on direct solicitation by charities as opposed to street beggars.

The fate of panhandling under the First Amendment remains less than clear. Some scholars contend that ordinances that regulate ordinary panhandling can be clearly distinguished from those that regulate menacing and intimidating behavior — aggressive panhandling. Others argue that city laws regulating panhandling are unconstitutionally vague and overbroad, deprive panhandlers of their free speech rights, and raise serious due process concerns by targeting the homeless. In this photo, Jess sits with his dog Plumkin in afternoon, Wednesday, Dec. 15, 1993, on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley, California, where he is one of the street’s regular panhandlers. (AP Photo/Eric Risberg, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Court has held that solicitation for money is intertwined with speech

In Schaumburg v. Citizens for a Better Environment (1980), a case dealing with the regulation of legitimate charities, the Court held that “solicitation for money is closely intertwined with speech” and that “solicitation to pay or contribute money is protected under the First Amendment.”

However, since Schaumburg the Supreme Court has allowed restrictions on a variety of direct solicitations where cities have found such activities inimical to the purpose of public space. For example, in Young v. New York City Transit Authority (2d Cir. 1990), the Court declined to hear an appeal challenging a New York City regulation prohibiting begging in the city’s subway system. In International Society for Krishna Consciousness v. Lee (1992), the Court upheld prohibitions on solicitation at a state fairground, on sidewalks outside of a post office, and within an airport terminal.

Panhandling rules can be overbroad

Thus far, although some lower courts have deemed panhandling to have some constitutional protection as “speech,” some have also recognized that communities have substantial leeway in devising regulations on “how and where” panhandling may occur within a community. And yet some courts have struck down for overbreadth laws in cities such as Austin, Texas, and Minneapolis, Minnesota, while upholding restrictive panhandling policies in cities such as Indianapolis, Indiana. In Madison, Wisconsin, the city ordinance was revised to avoid infringing on the free speech rights of panhandlers.

Reed decision has affected panhandling litigation

In 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court explained in Reed v. Town of Gilbert (2015) that laws that discriminate against speech on their face or in their purpose are considered content-based and are subject to strict scrutiny. The Court’s decision in Reed has had an impact on panhandling litigation, as the lower courts have invalidated numerous panhandling laws as impermissible content-based restrictions on speech.

For example, the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Norton v. City of Springfield (7th Cir. 2016) invalidated Springfield, Illinois’ panhandling ordinance as unconstitutional. Springfield’s ordinance banned only oral requests for immediate money but did not address signs requesting money or oral requests for money later.

Some panhandling laws only regulate the location where solicitations for money take place. Even under Reed, such laws may be content-neutral time, place and manner restrictions on speech.

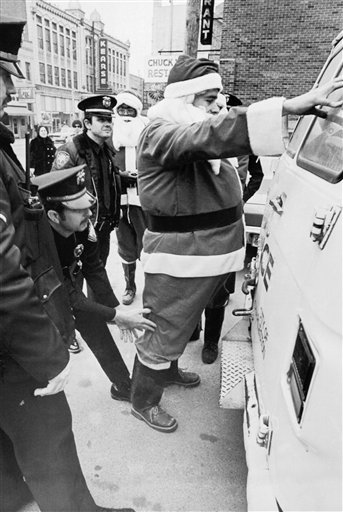

A policeman frisks one of three members of the Hare Krishna sect from Cleveland, Ohio, who were arrested, Dec. 12, 1976 in Charleston, West Virginia while soliciting funds in Santa Claus suits. These three were charged with panhandling. (AP Photo, Used with permission from The Associated Press.)

Ordinances restricting solicitation must pass intermediate scrutiny

City ordinances restricting solicitation in a public place must pass intermediate scrutiny and

- (1) be neutral in content;

- (2) be narrowly tailored;

- (3) leave open ample alternative channels of communication;

- and (4) serve a significant government interest that is pressing and legitimate.

Even under intermediate scrutiny, many panhandling ordinances have been invalidated. For example, the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Cutting v. City of Portland (1st Cir. 2015) struck down Portland, Maine’s ordinance that prohibiting panhandling while standing on median strips because it was not narrowly tailored and banned too much expressive activity.

Fate of panhandling under First Amendment remains unclear

Thus, the fate of panhandling under the First Amendment remains less than clear. Some scholars contend that ordinances that regulate ordinary panhandling can be clearly distinguished from those that regulate menacing and intimidating behavior — aggressive panhandling. Others argue that city laws regulating panhandling are unconstitutionally vague and overbroad, deprive panhandlers of their free speech rights, and raise serious due process concerns by targeting the homeless.

In spite of the strong views on both sides of this issue, the plethora of city actions that regulate and criminalize panhandling today arguably speak more to the lack of clarity from the Supreme Court on the issue.

As shown, cities can enact ordinances that properly regulate the time, place, and manner of panhandling without completely prohibiting begging, as long as such ordinances are content neutral and do not burden people’s abilities to exercise their free speech rights. Such a regulation would be constitutional because neither intimidating conduct nor threatening speech is a recognized communication protected under the free speech guarantees of the First Amendment.