The 1960s and 1970s witnessed numerous challenges to attempts by public schools to regulate their students’ hair length and style. Although the U.S. Supreme Court never accepted a case on the subject — a related case, Kelley v. Johnson (1976), dealt with grooming codes in a police department — Justice William O. Douglas dissented on a number of occasions from the Court’s decision not to hear such cases, which had split lower courts.

Douglas dissented on the Court’s decisions to not hear cases on public school regulation of hair length

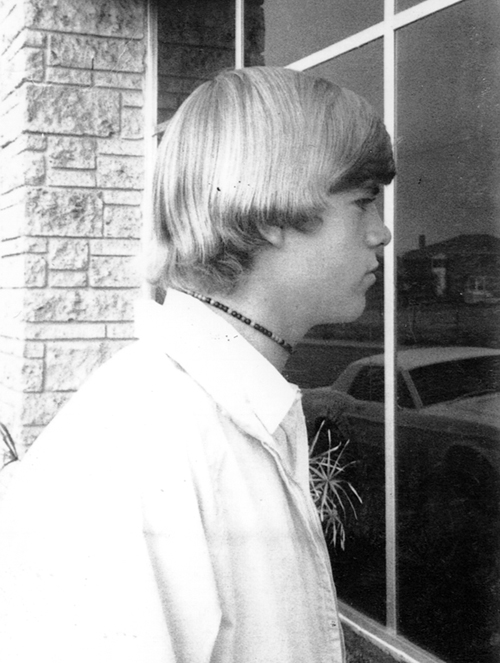

Douglas filed his most extensive dissent in Olff v. East Side Union High School District, 404 U.S. 1042 (1972), in which a school had refused to allow a 15-year-old boy, who had the support of his mother, to attend until he adhered to its policy. It forbade boys from wearing hair that fell below their eyes, covered their ears, or extended over their collars.

Douglas pointed that that the decision in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969), which had recognized the right of students to wear black arm bands in protest of the Vietnam War had also recognized their personhood. He further cited the decision in Prince v. Massachusetts (1944) in support of the right of parents to decide on most matters of child rearing and of the decision in Meyer v. Nebraska (1923) upholding a family’s right to provide foreign language instruction for their children. He noted that Meyer had distinguished the American way from the Spartan practice of entrusting such issues solely to the state. He also thought that it was silly to punish an otherwise harmless style simply because one’s neighbors opposed it.

Douglas further tied “liberty” to the fundamental rights recognized in Griswold v. Connecticut [the Connecticut birth control case that helped confirm the right to privacy] (1965) and the Ninth Amendment [which addressed rights reserved to the people]. Acknowledging that a school might decide to mandate short hair if it had an outbreak of lice, he did not see any justification for such regulations in this case. He pointed out that styles varied and noted how public opinion in the 1920s was often critical of women who “bobbed” their hair.

Douglas filed a shorter but similar dissent in Ferrell v. Dallas Independent School District, 393 U.S. 856 (1968). In that case, he further cited the Declaration of Independence and the Equal Protection Clause, both of which he said were inconsistent with the idea of “turning out robots.”