Supreme Court decisions over the years have affirmed that the First Amendment covers artistic expression, as exemplified in motion pictures, plays, and movies. Most challenges to music and accompanying lyrics have focused on claims that the lyrics are obscene, that they incite violence, or that they are harmful to minors.

Courts have protected music against obscenity, incitement charges

In an early famous case, a New York court acquitted the publisher John Peter Zenger in 1735 for printing lyrics to ballads critical of the British colonial governor. Centuries after Zenger, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals would state in Cinevision Corporation v. City of Burbank (1984), in which it overruled a city council’s denial of access to an amphitheater, “[M]usic is a form of expression that is protected by the First Amendment.”

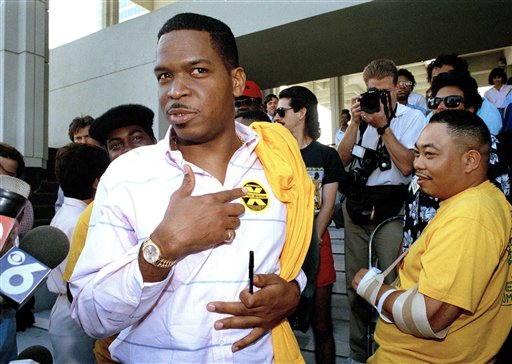

In February 1990, Broward County, Florida, sheriff’s deputies sought a judge’s opinion about the contents of 2 Live Crew’s As Nasty As They Wanna Be. Judge Mel Grossman stated that the album was probably obscene, and uniformed deputies delivered advisory letters to retailers, warning that continued sale of the disc could result in arrest. In response, 2 Live Crew’s label filed suit in a federal district court in Florida 1990 in Skyywalker Records v. Navarro, arguing against a prior restraint for the finding on obscenity. Judge Jose Gonzalez found affirmatively on both points; his opinion was overturned on appeal by the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals in Skyywalker Records v. Navarro (1992). Florida authorities’ appeal to the Supreme Court was denied.

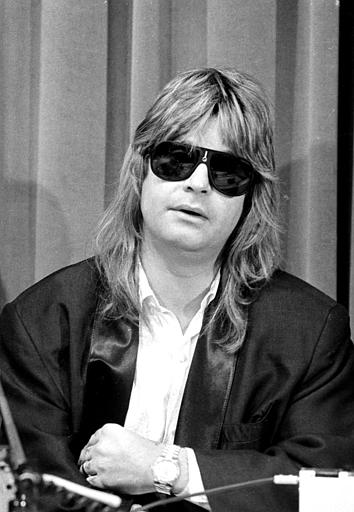

Waller v. Osbourne (11th Cir. 1992) is a music censorship case against the singer Ozzy Osbourne. In this photo, Osbourne speaks at a news conference in Los Angeles, on Jan. 21, 1986, after being sued by a California couple who claim his song, “Suicide Solution,” drove their teenage son to commit suicide. The plaintiffs argued that Osbourne’s lyrics used “inciteful speech,” but the appellate court ruled in his favor, holding that damages could attach only if it was the intention of the singer to cause the ensuing injury. The Supreme Court refused certiorari. (AP Photo/Lacy Atkins, used with permission from the Associated Press)

In Judas Priest v. Second Judicial District Court (Nev. 1988), in which two heavy metal artists were brought to court separately on grounds that their music caused suicide attempts by young listeners, it was argued that the Supreme Court’s opinion in Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), permitting the regulation of speech that incites “imminent lawless action,” applied. The plaintiffs in Judas Priest maintained that “back-masked messages” (reversed sound sequences) caused the suicide attempts. However, using the master tape of the music recordings in question, the plaintiffs could not isolate the alleged messages or persuasively argue the causal connection.

Waller v. Osbourne (11th Cir. 1992) is a case similar to Judas Priest against the singer Ozzy Osbourne. The plaintiffs argued that Osbourne’s lyrics used “inciteful speech,” but the appellate court ruled in his favor, holding that damages could attach only if it was the intention of the singer to cause the ensuing injury. The Supreme Court refused certiorari.

The punk band Dead Kennedys’ 1985 recording Frankenchrist included an explicit poster by artist H. R. Giger. Despite a warning on the exterior of the package about potentially “shocking, repulsive, offensive” art inside, the group was charged with distributing material harmful to minors. The prosecution eded in a hung jury in summer 1987, and the state did not reprosecute.

Congress has investigated music and pop culture, along with attempting to pass some music legislation. In September 1985, the Senate Subcommittee on Communication of the Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee held a hearing catalyzed by the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC), co-founded by Tipper Gore. The PMRC advocated an extensive, content-based labeling system for sound recordings. Although the subcommittee took no action, media attention surrounding the hearings empowered the PMRC to negotiate with the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) for voluntary Parental Advisory: Explicit Lyrics stickers to be placed on some products. In this photo, Tipper Gore, wife of Sen. Al Gore Jr. (D-Tenn.), left, and Susan Baker, wife of Secretary of State James A. Baker, appear at the PMRC (Parents Music Resource Center) committee hearing in Washington, Sept. 19, 1985. (AP Photo/Lana Harris, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Congress has investigated music and pop culture

Congress passed the Communications Decency Act (CDA) of 1996, which criminalized transmission of “indecent” and “patently offensive” material over the Internet. The Supreme Court issued a 7-2 decision in Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union (1997) affirming a lower court finding of the CDA as unconstitutional because it was overbroad and vague.

The Child Online Protection Act (COPA) of 1998, Congress’s response to the CDA ruling, was designed to protect minors from harmful sexual material on the Internet. COPA was challenged in Ashcroft v. American Civil Liberties Union (2002) and Ashcroft v. American Civil Liberties Union (2004), in which the Supreme Court upheld injunction against the law’s enforcement, holding that COPA as well was probably unconstitutional.

Even without contemplating legislation, Congress has held hearings investigating popular music and culture. In September 1985, the Senate Subcommittee on Communication of the Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee held a hearing catalyzed by the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC), co-founded by Tipper Gore. The PMRC advocated an extensive, content-based labeling system for sound recordings. Although the subcommittee took no action, media attention surrounding the hearings empowered the PMRC to negotiate with the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) for voluntary Parental Advisory: Explicit Lyrics stickers to be placed on some products.

In 1994 hearings catalyzed by the National Political Congress of Black Women (NPCBW) were held in both houses of Congress. NPCBW leader C. Delores Tucker urged legislators to regulate the recording industry. In 1997 the Senate Government Affairs Subcommittee heard testimony on the effect of popular music on youths. In September 2000, Congress held hearings on violent entertainment, including popular music, marketed to children.

This article was originally published in 2009. Paul Fischer, PhD, served on the faculty of Middle Tennessee State University’s Department of Recording Industry from 1996 to 2018. He is considered a pioneer in the field of Popular Music Studies.