In Masson v. New Yorker Magazine, 501 U.S. 496 (1991), the Supreme Court ruled that deliberately altering an interviewee’s words yet placing them in quotation marks did not constitute libel under the standards articulated in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964) and Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc. (1974), unless the alterations resulted in a material change in the meaning conveyed by the statement.

In 1980 psychoanalyst Jeffrey Masson became projects director of the Sigmund Freud Archives. Shortly thereafter, he became disillusioned with Freud’s theories and advanced his own theories about Freud. He was fired.

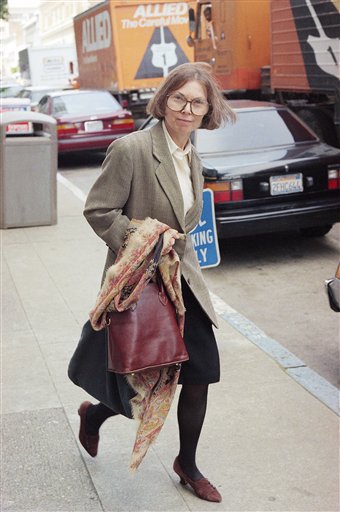

In 1982 journalist Janet Malcolm interviewed him at length about his experiences with the Archives, taping many, but not all, of the interviews. She then wrote an unflattering portrayal of him in a two-part series in The New Yorker magazine the following year. In 1984 Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. published the series as a book, In the Freud Archives.

Freud scholar argues he was misquoted, sues for defamation

That same year Masson published The Assault on Truth: Freud’s Suppression of the Seduction Theory. He also filed a libel suit against the The New Yorker, alleging that Malcolm misquoted him in several instances by altering his words yet placing them in quotation marks as if he had said them. These alterations, he argued, defamed him.

The U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California ruled that the allegedly fabricated quotes were either substantially true or reasonable interpretations of the conversations and thus were entitled to constitutional protection under the First Amendment. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed, and Masson appealed to the Supreme Court, which affirmed the lower court rulings.

Supreme Court says altering person’s comments could be protected if it didn’t materially change meaning

In his majority opinion for the Court, Justice Anthony M. Kennedy reasoned that a deliberate alteration of a person’s comments could constitute actual malice under traditional libel law standards if it led to a “material change in meaning.” He explained: “We conclude that a deliberate alteration of the words uttered by a plaintiff does not equate with knowledge of falsity … unless the alteration results in a material change in the meaning conveyed by the statement.”

Whether Malcolm acted with “requisite knowledge of falsity or reckless disregard as to the truth or falsity” was an issue for a jury to decide.

After the Court’s ruling and two jury trials, and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ended the dispute by affirming the judgment of the district court and ruling that Masson was barred from re-litigating these issues against The New Yorker.

However, the issue of how far a journalist can go in deliberately altering a speaker’s words under the concept of narrative journalism without running afoul of the First Amendment remains controversial.

This article was originally published in 2009. Dr. Judith Ann Haydel (1945-2007) was a political science professor at the University of Louisiana-Lafayette and McNeese State University.