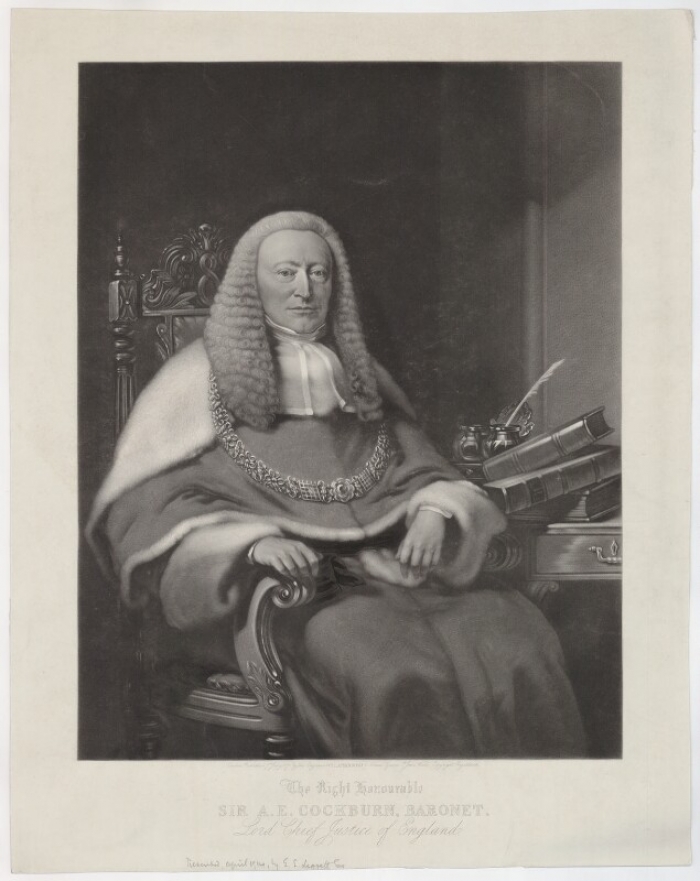

Named for Benjamin Hicklin, a nineteenth-century court recorder in London, England, the Hicklin Test is an obscenity standard that originated in an English case. In Regina v. Hicklin (1868), Lord Chief Justice Alexander Cockburn, writing for the Court of Queen’s Bench, supplied a broad definition of obscenity, based on ascertaining “whether the tendency of the matter is to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences and into whose hands a publication of this sort may fall.”

Hicklin Test used when publications could corrupt ‘susceptible’ minds

The Hicklin Test, developed in a country with no written constitution and thus no guaranteed First Amendment rights, was initially used in U.S. law. It ultimately did not survive constitutional challenges based on First Amendment and other considerations.

American courts adopted the Hicklin Test in applying the Federal Anti-Obscenity Act of 1873 (the Comstock Act) and subsequent state anti-obscenity statutes modeled on the federal act. The Hicklin Test permitted a conviction for purveyors of obscenity if a publication had a mere tendency to arouse lustful thoughts in the minds of the most susceptible, usually youthful, readers. Isolated passages could be used to determine whether there was sufficient evidence to infer a defendant’s intention to corrupt public morals. A defendant could not rebut this inference by arguing that a book was published in the public interest or by providing evidence of its literary merit.

Hicklin Test used to justify scrutiny, prosecution of literature

First employed by a circuit court in the Southern District of New York in United States v. Bennett (1879), a case in which the defendant was convicted of mailing a document advocating legalized prostitution, the Hicklin Test came to justify a wide-ranging official scrutiny of literature and the prosecution of serious works of contemporary fiction. Notable among them were Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy and D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover in 1930; James Joyce’s Ulysses in 1933; Edmund Wilson’s Memoirs of Hecate County in 1948; and Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer in 1953.

Hicklin Test questioned, altered by courts

The first case to question the Hicklin Test’s applicability “to the morality of the present time” was United States v. Kennerley (S.D.N.Y. 1913). Later federal court decisions altered the test in various ways: United States v. Dennett (2d Cir. 1930) by requiring that a work be judged by its dominant theme; United States v. One Book Named Ulysses (2d Cir. 1933) that it undergo independent literary analysis and be judged by its effect on a person of average sexual instincts; United States v. Levine (2d Cir. 1936) that its lustful effect on the reader outweigh its literary or scientific merits; and Parmelee v. United States (D.C. Cir. 1940) that it be judged, as in Kennerley, by contemporary community standards.

Court created new obscenity tests

Although the Supreme Court had decided cases involving obscenity convictions as early as 1896, it did not address their First Amendment issues until 60 years later. The Court rejected the Hicklin Test’s “most susceptible person” requirement in Butler v. Michigan (1957) and then scrapped the test itself in Roth v. United States (1957).

Justice William J. Brennan Jr., in his opinion for the Court in Roth, upheld the use of the Comstock Act and a similar state statute, declaring that obscenity was not protected First Amendment speech. He then crafted a new obscenity test. The new test required that a conviction be based on a finding that the average person applying contemporary community standards would feel that the dominant theme of the material taken as a whole appealed to a prurient interest in sex. This test, has, in turn, been modified by the Court’s decision in Miller v. California (1973).

This article was originally published in 2009. Dr. William C. Green (1954-2020) was a professor of political science and government at Morehead State University.