In Healy v. James, 408 U.S. 169 (1972), the Supreme Court affirmed public college students’ First Amendment rights of free speech and association, determining that those constitutional protections apply with the same force on a state university campus as in the larger community.

Public college denied official status to student group

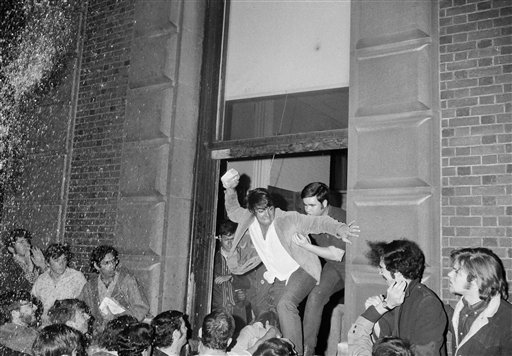

At Central Connecticut State College, the school president Dr. James had denied official status to the local chapter of a left-wing student group, Students for a Democratic Society, who had been associated with violence on other campuses. The president said the group’s philosophy was “antithetical to the school’s policies,” its independence from the national organization was “doubtful,” and it would be “disruptive.” Without official status, the group could not announce its activities in the campus newspaper, post notices on college bulletin boards, or use campus facilities for meetings. Healy, a student, had appealed Dr. James’s decision, which two lower federal courts had affirmed.

Campuses students aren’t exempt from First Amendment protections

Writing for an eight-member majority, Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. observed at the outset that the case arose in 1969 when a climate of unrest on many U.S. college campuses was marked by civil disobedience. Powell quickly established that “state colleges and universities are not enclaves immune from the sweep of the First Amendment.” He cited the Court’s declaration in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969) that neither public secondary students nor their teachers “shed their constitutional rights of freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” Though the Court had long recognized that officials must govern conduct in the public schools, Powell emphasized precedents “leave no room for the view that, because of the acknowledged need for order, First Amendment protections should apply with less force on college campuses than in the community at large.” The college classroom and its surroundings are a distinct “marketplace of ideas,” Powell wrote.

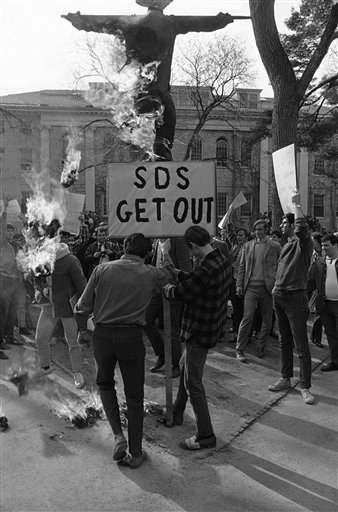

Harvard students staged a protest in Harvard Yard, Cambridge, Massachusetts, on April 22, 1969, in arms against Students for a Democratic Society and burned an effigy as other students held posters. The Supreme Court ruled in 1972 that colleges could not deny SDS for purely ideological reasons. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Colleges can impose reasonable restrictions on student association

Because denial of official status was in effect a form of prior restraint, Powell reasoned, a “heavy burden” rested on the college to justify its action. The college president could not deny recognition simply because he disagreed with the philosophy or ideas advocated by the students, regardless of how repugnant or abhorrent he found those views.

However, relying on Tinker, Powell said colleges could prohibit students’ associational activities that would “infringe reasonable campus rules, interrupt classes, or substantially interfere with the opportunity of other students to obtain an education.” Schools also could impose reasonable time, place,and manner restrictions on student speech and require that groups seeking official recognition agree in advance to conform to “reasonable campus law.” The Court remanded the case to ascertain whether the students were willing to abide by “reasonable campus rules and regulations.”

Justice William H. Rehnquist concurred only in the result, saying the majority opinion obscured distinctions that allow the government as school administrator to impose reasonable rules and sanctions on students that as a sovereign it could not impose on all citizens.

Colleges stop dissemination of ideas only due to philosophical disagreements

A year later, in Papish v. Board of Curators of the University of Missouri (1973), the Court said Healy made “clear that the mere dissemination of ideas—no matter how offensive to good taste—on a state university campus may not be shut off in the name alone of ‘conventions of decency.’”

This article was originally published in 2009. Joey Senat, Ph.d., teaches mass communication law and multimedia journalism in Oklahoma State University’s School of Media & Strategic Communications. He is the author of Mass Communication Law in Oklahoma and Our Right to Know in Oklahoma. Dr. Senat received the 2007 Marian Opala First Amendment Award and the 2005 Oklahoma Society of Professional Journalists Award for Distinguished Service to the First Amendment.