Although the First and Fourteenth Amendments are designed to guard against governmental suppression of religion, speech, press, assembly and petition, individuals might also suffer penalties for the exercise of such rights from private actors.

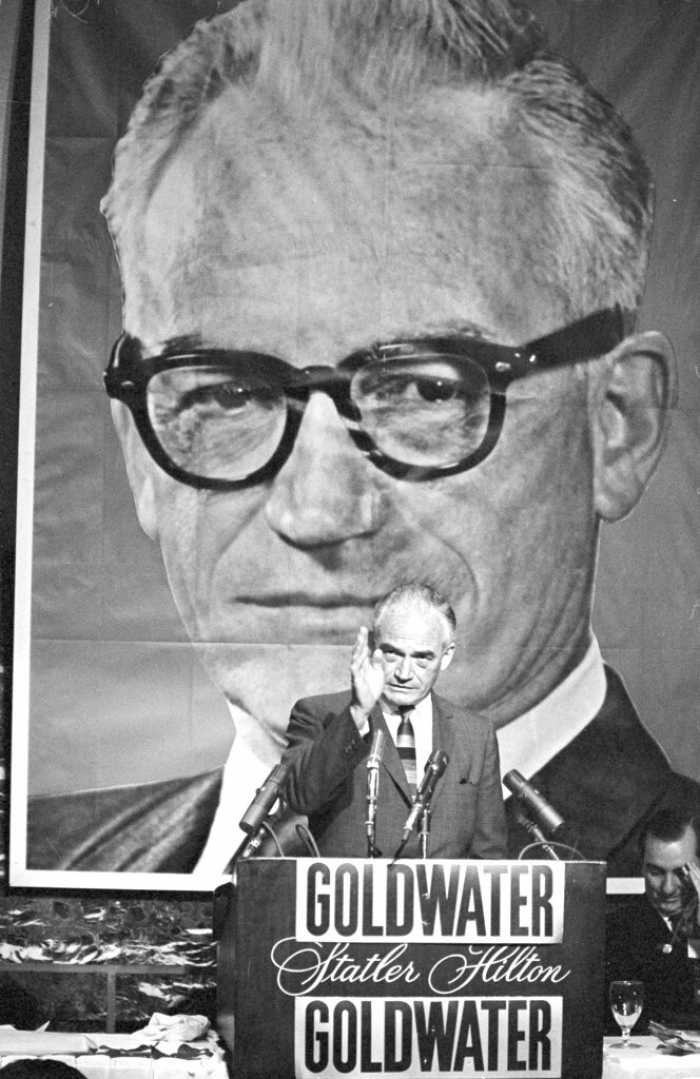

One such limit that has been enforced by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) on its members since 1973 is the so-called Goldwater Rule. The rule was formulated in reaction to an article published by Fact magazine in 1964. The magazine had asked psychiatrists to assess the mental competence of Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, who was running against President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Goldwater had a reputation as a war hawk and was often associated with the statement “better dead than red,” meaning it was better to die than to be a slave to communism. Although the phrase was arguably similar in sentiments to Patrick Henry’s famed speech in which he reputedly cried “Give me liberty or give me death!” some psychiatrists took Goldwater’s words literally and feared that he might unleash a nuclear war (Weissman 2018, 23).

Goldwater wins libel suit against magazine

In response to the question, “Do you believe Barry Goldwater is psychologically fit to serve as President of the United States,” 1,189 of the 2,417 responding psychiatrists (a total of 12,256 had been queried) said no. In a 41-page article, Fact magazine quoted psychiatrists who compared Goldwater to brutal and arguably unhinged dictators often using psychological classifications in doing so. Goldwater later won a libel suit that helped put the publication out of business.

Feeling that this had given psychiatry a bad name, the American Psychiatric Association created the Goldwater Rule prohibiting members from giving armchair psychological opinions about individuals whom they had not personally examined. They strengthened this rule in 2017 amid increasing speculation that President Donald J. Trump might be suffering from a psychological disorder such as narcissism.

Goldwater Rule prevents professional from offering opinion, critics say

Critics of the rule believe that it effectively removes professionals who are most likely able to judge such mental states from public fora and leaves the field open for individuals without such psychological training to proffer such evaluations. Moreover, it is not at all uncommon for medical doctors to comment on the health or possible prognoses of public figures whom they have not physically examined, as, for example, when President Trump was admitted to the hospital with COVID-19.

Leonard Glass, an associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School is among those who believe that the psychiatric association’s prohibition conflicts with the profession’s “duty to warn” in cases where conditions appear obvious. He and others suggest that the solution is not a blanket gag rule against psychiatrists who wish to give their opinion based on publicly available information but rather a caution that psychiatrists who proffer such opinions should make it clear that they have not actually had the opportunity to conduct a one-on-one session with such an individual.

This issue arose again in 2021 when Dr. Bandy X. Lee, a psychiatrist at Yale University, sued the university when it did not renew her teaching appointment after she suggested in a tweet that attorney and former Harvard law professor Alan M. Dershowitz, who had defended Trump in his first impeachment trial, might have a “shared psychosis” with the president he was defending (Zaveri, 2021). The suit is complicated by the fact that Yale is a private, rather than a governmental, institution.

Whatever its outcome, the case has brought attention to an issue that is likely to be the object of continuing discussion.

John R. Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the University Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. This article was published April 1, 2021.