A number of the Puritans who came to America immigrated from Holland, which had a much more liberal policy toward Protestant religious freedom than many of the Pilgrims themselves established in America.

In 1645, Governor Willem Kieft of New Netherlands (today’s New York) granted a charter to settlers in Flushing (in today’s Queens) “to have and enjoy liberty of conscience, according to the custom and manner of Holland, without molestation or disturbance” (Freeman 1958, 806, n.1). One very practical reason for such a policy was the belief that it would encourage immigration.

Governor banishes man who hosted Quakers

When Governor Peter Stuyvesant, a staunch Calvinist, took office, however, he fined Henry Townsend for allowing Quakers to meet in his house and banished him to Holland (Peabody 2005). Although today’s Quakers are largely known for their pacifism, in Stuyvesant’s day they were considered to be “belligerent and boisterous rabble-rousers,” who were “aggressive proselytizers.” One of the reasons William Penn later founded Pennsylvania was to provide a haven for them (ZHU 2014).

Remonstrance described Bible's instruction on religious tolerance

In response to Stuyvesant’s actions, 30 citizens adopted what became known as the Flushing Remonstrance on December 17, 1657. It observed that they could not condemn Quakers because the Bible commanded them “not to judge least we be judged,” and because they were “bounde by the Law to doe good unto all men, especially to those of the household of faith” (Freeman, 806). Citing Moses, the remonstrance observed that “the Lord hath taught Moses or the civil power to give an outward liberty in the state by the law written in his heart designed for the good of all” (806-7).

Going well beyond the freedom guaranteed in Holland, the petition noted that Jesus Christ condemns “hatred, wear and bondage,” and that “the law of love, peace and liberty” extended “to Jews, Turks, and Egyptians” as “the sonnes of Adam” and that “our desire is not to offend one of his little ones, in whatsoever form, name or title hee appears in, whether Presbyterian, Independent, Baptist or Quaker, but shall be glad to see anything of God in any of them” (807). The Remonstrance observed that “we are true subjects both of Church and State, for we are bounde by the law of God and man to doe good unto all men and evil to noe man” (807)

Governor Stuyvesant responded by imprisoning the town clerk and removing some council members and magistrates from office. He also declared a day of prayer so that the people would not be judged for sheltering “a new unheard of, abominable Heresy” (Zhuy 2014).

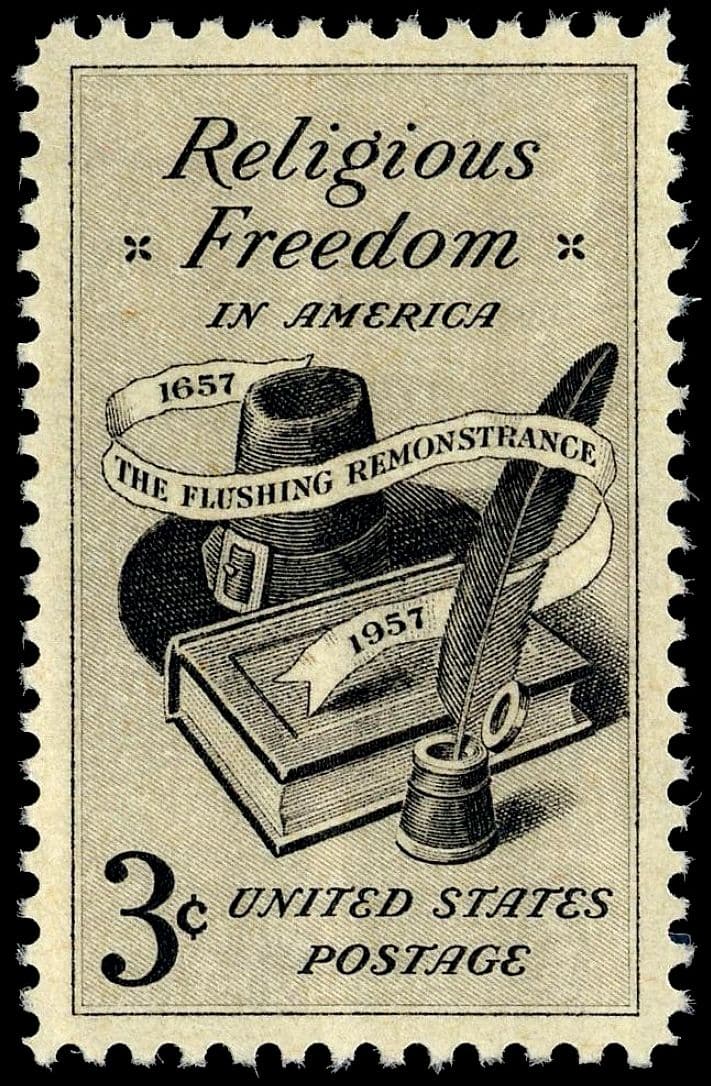

In 1957, U.S. issues stamp to commemorate Flushing Remonstrance

Somewhat later, John Bowne became a Quaker and opened his house to them after which he was confined and deported. In time, however, the West Indian Company, perhaps fearing that the governor’s policies were impeding immigration, acquitted Bowne, revoked his banishment, and ordered Stuyvesant to end religious persecution. In 1957, Bowne’s House was dedicated as an example of early English liberty and a 3-cent stamp was issued commemorating the 300th anniversary of the Remonstrance as a case of “Religious Freedom in America.”

One writer, notes that “the Flushing Remonstrance presents a unique instance of Dutch religious rule and tolerance interpreted through English Protestant lenses.” He believes that the Document is important because it “was not written by the persecuted, but by those who wanted to help them” (Zhu 2014).

Although the Flushing Remonstrance has been called “the religious Magna Carta of the New World” (Reed 2020) and is similar to the idea of the free exercise clause of the First Amendment, it is absent from most early records and is not known to have any direct influence on Governor Stuyvesant’s religious policies (Zhu 2014).

John R. Vile is a political science professor and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University.