Many Supreme Court decisions, including Feiner v. New York, 240 U.S. 315 (1951), have addressed the issue of whether speech that incites a “breach of the peace” constitutes a categorical exception to the First Amendment. Taken together, these cases render unprotected those communications that threaten an immediate breach of the peace.

Feiner arrested after inflammatory speech caused unruly crowd

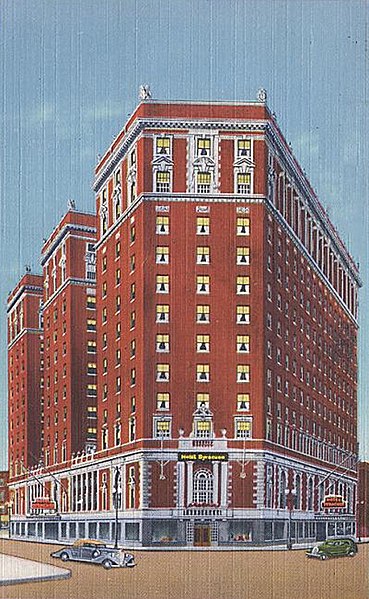

In March 1949, Irving Feiner, a college student, addressed a crowd on a street corner in Syracuse, N.Y. He encouraged listeners to attend a meeting to be held later at a hotel, urged blacks to “rise up in arms and fight for equal rights,” and uttered “derogatory remarks concerning President [Harry] Truman” and other political officials.

When the police arrived, members of the crowd remarked on the inability of the police to handle the crowd, and “at least one threatened violence” toward Feiner. Police asked Feiner three times to end his speech, but he refused to do so. After the third request, police arrested him. He was convicted for disorderly conduct, a misdemeanor, and sentenced to 30 days in the county jail.

Court upheld Feiner’s conviction for his conduct, not his speech content

At trial, the judge concluded that “police officers were justified in taking action to prevent a breach of the peace.” And the U.S. Supreme Court ultimately upheld Feiner’s conviction. Chief Justice Frederick M. Vinson wrote the opinion for a five-justice majority, asserting that Feiner was not convicted for the content of his speech but for his conduct, which Chief Justice Vinson identified as “incitement to riot” and “refusal . . . to obey the police requests.”

In his opinion, Vinson relied on Cantwell v. Connecticut (1940): “When clear and present danger of riot, disorder, interference with the traffic upon the public streets, or other immediate threat to public safety, peace, or order, appears, the power of the State to prevent or punish is obvious.”

Dissenting justices said breach of the peace was not imminent

Justices William O. Douglas and Hugo L. Black wrote passionate dissents.

Both justices argued that the evidence failed to demonstrate that a breach of the peace was imminent. Justice Black complained that the police officers’ “duty was to protect petitioner’s right to talk, even to the extent of arresting the man who threatened to interfere. Instead, they shirked that duty and acted only to suppress the right to speak.” Justice Douglas feared that Feiner would invite law enforcement officials to “become the new censors of speech.”

Feiner’s actions put in category of speech not protected by the First Amendment

The clash between the majority and dissenting opinions in this case mirrored a debate on the scope of free expression under way in the United States.

In Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942), the Court unanimously affirmed that certain categories of speech constitute exceptions to the First Amendment. “ ‘Fighting words’ — those which by their very utterance inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace” — constitute one categorical exception. When the majority categorized Feiner’s words and actions as a breach of the peace, they located his speech beyond the ambit of the First Amendment.

Dissenting justices said courts have a responsibility to protect speakers from ‘heckler’s veto’

However, when police repress speech to prevent violent retaliation from audiences, the law imposes a “heckler’s veto” upon communicators.

In Feiner, Justices Douglas and Black offered a detailed rationale for the claim that the courts have a responsibility to protect speakers from hostile audiences. Douglas had authored the majority opinion in Terminiello v. Chicago (1949), in which the Court had overturned a disorderly conduct arrest of a priest whose speech to a sympathetic audience had stirred the passions of a crowd outside.

This article was originally published in 2009. Richard A. “Tony” Parker is an Emeritus Professor of Speech Communication at Northern Arizona University. He is the editor of Speech on Trial: Communication Perspectives On Landmark Supreme Court Decisions which received the Franklyn S. Haiman Award for Distinguished Scholarship in Freedom of Expression from the National Communication Association in 1994.