According to the Supreme Court in Buckley v. Valeo (1976), express advocacy is the use of words such as “vote for,” “elect,” or “support” in political communications. Although political communications are entitled to First Amendment protection, the spending of money for such communications may be limited.

Efforts made to restrict political campaign finance

Efforts have been made for more than 100 years to restrict who can give money and how much they can give to influence elections. The Tillman Act of 1907 banned corporations from spending money to influence federal elections, and then the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 did the same for labor unions. The fundraising scandals surrounding the election of President Richard M. Nixon in 1972 spurred new efforts to restrict the spending of money for political purposes.

Court ruled that First Amendment was implicated in campaign finance

The issue of express advocacy first came before the Supreme Court in 1976 in Buckley v. Valeo, when the Court had to rule on the constitutionality of the Federal Election Campaign Act amendments of 1974, which contained limits on political contributions and expenditures.

In that case, although the Court did not say money was speech for the purposes of the First Amendment, it did rule that First Amendment concerns were implicated both in political contributions and in expenditures.

Because they raised free speech issues, neither political contributions nor expenditures could be limited unless the government could show that such limitations would address an overriding compelling governmental interest in addressing corruption or its appearance.

The Court ruled that although it did not then see how the quantity of campaign expenditures could corrupt the political process, and therefore could not be limited, political contributions to candidates did raise potential concerns about corruption that constitutionally could be addressed by limiting how much individuals or political organizations could give.

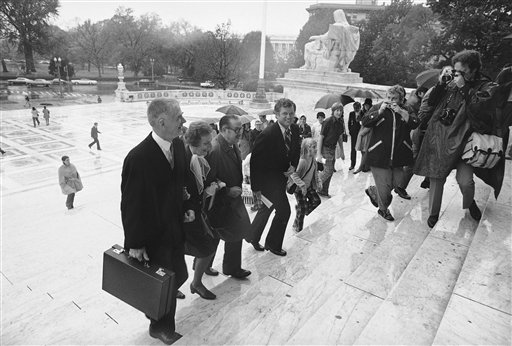

In this photo, several men enter the Supreme Court in 1975, to hear arguments on the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1974 in Buckley v. Valeo. This case was the first where the issue of express advocacy came before the Supreme Court. In it, the Court ruled that the First Amendment was implicated in campaign finance. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Court distinguished between express and issue advocacy

In general the Court appeared unwilling to limit political expenditures, but by making a distinction between express and issue advocacy, it allowed restrictions on unions and corporations to remain in place. Although political communications by these and other groups that expressly advocated the election or defeat of a federal candidate could be regulated, those that did not use the “magic words” of “vote for,” “oppose,” or similar words constituted issue advocacy, which could not be limited. The Court reasoned that issue advocacy was pure political speech that did not raise concerns about corruption.

As a result of the distinction between express and issue advocacy in Buckley, groups sought to bypass federal restrictions by running political ads and communications that did not use the magic words, although the ads would often show pictures of candidates they opposed. This meant, among other things, that despite the Tillman and Taft-Hartley Acts, corporations and labor unions could find a constitutional way to influence federal elections.

In some cases these groups and others were legitimately engaged in issue advocacy, but the distinction between express and issue advocacy left, for many, a large hole in the campaign finance laws.

Lower courts disagreed on whether ‘magic words’ had to be present for express advocacy

In the years that followed Buckley, almost all the federal appeals courts that considered the issue took the view that a communication must contain express words of advocacy to qualify for federal regulation. The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, by contrast, found in Federal Election Commission v. Furgatch (1989) that in order to qualify as express advocacy, a communication need not contain magic words so long as it unmistakably and unambiguously suggested only one plausible meaning, presented a clear plea for action, and clearly articulated the action it intended to elicit.

The 9th Circuit also explained that a communication could not be considered express advocacy if reasonable minds could differ as to its intent. Many circuit courts subsequently rejected this “reasonable person” standard.

In McConnell v. Federal Election Commission (2003), the Supreme Court upheld the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (BCRA) against a First Amendment challenge from Sen. Mitch McConnell, pictured here at the Supreme Court in 2003. The law had introduced a new term — electioneering communications — to resolve the debate about issue advocacy versus express advocacy. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert, used with permission from the Associated Press)

BCRA introduced ‘electioneering’ to resolve ambiguity about express advocacy

The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (BCRA) introduced a new term — electioneering communications — to resolve the debate about issue advocacy versus express advocacy by slating for regulation all communications falling within its scope. The statute was intended to close a loophole created by the Court’s decision in Buckley, which allowed groups to spend huge sums on advertisements that closely resembled traditional campaign ads but which escaped regulation by avoiding terms of express advocacy.

The law defines “electioneering communications” as broadcast, cable, or satellite communications targeted at the relevant electorate and referring to a clearly identified federal candidate that are made within 60 days of a general election or 30 days of a primary election. Congress also included a backup definition (in case the first definition was ruled unconstitutional), which integrated the reasonable person test articulated in Furgatch.

The statute exempts from regulation the media, independent expenditures, and candidate debates and forums, and it grants the Federal Election Commission (FEC) authority to make additional exemptions consistent with the purposes of the law. Congress defined “independent expenditure” as spending for the purpose of expressly advocating the election or defeat of a federal candidate, so long as the money is not spent at the request of, or in cooperation with, the candidate or the candidate’s political party.

BCRA was immediately challenged on First Amendment grounds

The BCRA was almost immediately challenged in court by those who thought that several of its provisions (including the one defining “electioneering communications”) violated the First Amendment freedom of speech clause. In McConnell v. Federal Election Commission (2003) the Supreme Court affirmed the primary definition of electioneering communications and so did not need to resolve the constitutional validity of the Furgatch-inspired secondary definition.

The Court concluded that advertisements broadcast within 30 days of a primary or 60 days of a general election were “the functional equivalent of express advocacy” and could be regulated accordingly. The Court also found that the Constitution drew no distinction between express and issue advocacy and accordingly invalidated the magic words test.

Exercising its delegated authority to make exemptions to the BCRA’s electioneering communications provision, the FEC adopted rules that excluded from regulation all unpaid broadcast communications by tax exempt organizations and all communications distributed on the Internet. In 2004 and 2005, respectively, the District of Columbia district and circuit courts struck down the regulations in Shays v. Federal Election Commission. On remand, the commission adopted a new definition of “public communication” that includes communications posted for a fee on the Internet.

Express advocacy distinction from Buckley remains good law

Although McConnell seemingly resolved the BCRA’s constitutionality, the Court left the door open to as-applied challenges to the law. In Federal Election Commission v. Wisconsin Right to Life, Inc. (2007) the Supreme Court struck down on First Amendment grounds as applied the 30 and 60 day rule found in the BCRA that it had upheld in McConnell.

Effectively, this ruling means that the express versus issue advocacy distinction articulated in Buckley remains good law and that efforts to restrict issue advocacy are unconstitutional. It also means that in some cases express advocacy may be regulated under the conditions specified in Buckley.

This article was originally published in 2009.Danielle Rosengarten graduated from American University Washington College of Law.