In Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U.S. 229 (1963), the Supreme Court ruled that South Carolina had violated students’ First Amendment rights of peaceable assembly, speech, and petition when the police dispersed a peaceful protest against segregation. The case illustrates one of the roles played by the First Amendment in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

South Carolina students arrested during peaceful protest

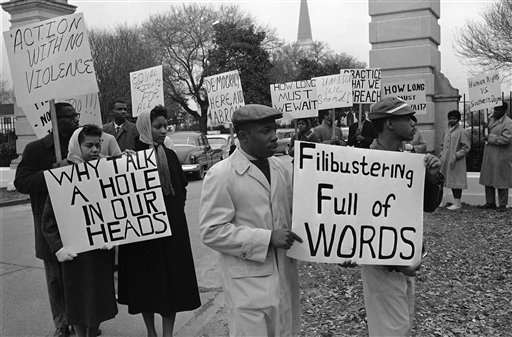

The case began on March 2, 1961, when a group of African-American high school and college students marched on the South Carolina State House grounds in Columbia to protest segregation. Carrying placards reading “Down with Segregation” and similar protest phrases, the students walked single and double file for approximately 45 minutes, attracting a crowd of 200 to 300 onlookers, when the police gave them 15 minutes to disperse.

Instead of leaving, the students chanted patriotic and religious songs. At the end of the 15 minutes, police officers arrested the students. A magistrate’s court in Columbia convicted 187 students for violating a breach-of-the-peace law. The convictions carried a fine of between $10 and $100 and a jail sentence of 10 to 30 days. The South Carolina Supreme Court affirmed the convictions.

Court said students exercised basic First Amendment rights

In the majority opinion for the Supreme Court, Justice Potter Stewart wrote that the students’ actions “reflect an exercise of these basic constitutional rights [to speech, assembly, and petition] in their most pristine and classic form.” Stewart emphasized that the students acted peaceably and never threatened violence or harm. He concluded that the First and 14th Amendments do not “permit a State to make criminal the peaceful expression of unpopular views.”

Dissenting justice said demonstration was not ‘passive’

Justice Tom C. Clark, in a lone dissent, asserted that the majority understated the facts that faced the police in Columbia and that the students’ actions were “by no means the passive demonstration which this Court relates.”

He believed that the police had acted reasonably in preventing a possible riot. “But to say that the police may not intervene until the riot has occurred is like keeping out the doctor until the patient dies,” he wrote.

In Adderly v. Florida (1966), the Court would distinguish demonstrations on state capitol grounds from similar demonstrations on the grounds of a jail.

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.