The Confederate flag continues to generate controversy and impassioned debates with implications for the First Amendment.

The flag most commonly displayed as representing the Confederacy is the Beauregard battle flag, also known as the Southern Cross. This flag was widely used by Southern troops during the Civil War, but it was never officially adopted by the Confederacy. The appropriation of the Confederate flag by white supremacist organizations, such as the Ku Klux Klan, makes the debate over it particularly emotional.

Some people view the flag as a symbol celebrating racism and regard the use of Confederate symbols in state flags or their display on state property as offensive; to other individuals it represents Southern heritage, and they assert their right to display the flag of the Confederate South wherever they like.

The Supreme Court, while allowing the removal of the Confederate flag to stop disruption, has declined to find that flag infringes upon the rights of those who find it repugnant. In this photo, a white woman stands in protest by a Confederate flag fluttering in the breeze as a group of 20 civil rights marchers pass through Hammond, Louisiana, in 1967. (AP Photo/Jack Thornell)

Court rejects case that Confederate flag display violated constitutional rights

The use of the Confederate battle flag in state flag designs reached the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in 1997 in Coleman v. Miller, in which James Andrew Coleman sued to stop Georgia from flying its state flag over state office buildings.

Coleman, an African American, alleged that the use of the Confederate battle flag emblem in the state flag violated his right to equal protection under the 14th Amendment and his right of free expression under the First Amendment. The 14th Amendment argument focused on the exclusionary message that Coleman asserted the flag sent to him as an African American; he held that it represented the state’s segregationist history and slavery. The First Amendment argument focused on the flag as symbolic speech. Coleman proffered that, as a citizen, he was being forced to represent a position that he found morally repugnant.

The court focused most of its attention on the equal protection argument ultimately dismissing it. It also rejected the First Amendment argument, on the ground that the display of the flag did not compel the individual affirmatively to acknowledge the message represented by the flag. Had the state, however, required Coleman to display the flag on his license plate, it would have run afoul of the First Amendment.

The NAACP campaign edin 1994 to remove the Confederate battle flag from the South Carolina state capitol in Columbia, where it had flown since 1962. The campaign included an economic and tourism boycott coupled with an extensive public relations campaign that caused revenue losses for the state. Eventually, a compromise was reached to remove the flag from the statehouse dome to a less prominent place on the grounds where it served as part of a Civil War memorial. In 2015, Gov. Nikki Haley signed a bill also removing this flag in the wake of the murder of nine black members of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston by a white supremacist. In this photo, two men hold up Confederate flags in a counterprotest at the South Carolina statehouse. (AP Photo/Mary Ann Chastain)

Activists have campaigned to remove Confederate flag from state property

After the courts upheld the constitutionality of Georgia flag display, activists turned to other tactics to remove similar displays from public property.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People launched a campaign to remove the battle flag from the South Carolina state capitol, where it had flown since 1962. The campaign included an economic and tourism boycott coupled with an extensive public relations campaign that resulted in significant losses in revenue for the state.

The campaign initially ended in a compromise that removed the flag from the statehouse dome to a less prominent place on the grounds, where it served as part of a Civil War memorial. In 2015, Governor Nikki Haley signed a bill also removing this flag in the wake of the murder of nine black members of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church by a white supremacist.

Other states have also removed the Confederate flag from state property, often in incremental fashion.

In 2001, Mississippi voters rejected a revised design of its state flag — which was adopted in 1894 and prominently displays the Confederate battle flag — making their state the only one that continued to incorporate the Confederate flag in its official flag. In 2020, however, the state legislature passed a bill, which the governor signed, to finally remove the Confederate symbol.

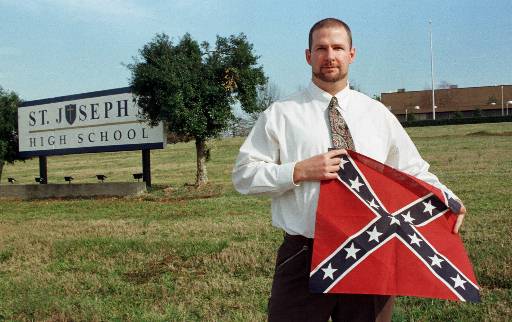

Courts have upheld the removal of the Confederate flag from schools and workplaces under policies designed to limit disruption. In this photo, Winston McCuen holds the Confederate banner which he had displayed in his history class at St. Joseph’s High School as he stands outside the school on March 23, 1999, in Greenville, South Carolina. McCuen, who is part of a growing Southern separatist movement, was fired by the private Catholic school’s headmaster after protesting the removal of the flag. (AP Photo/Mary Ann Chastain)

Courts have upheld rights of schools, employers to ban Confederate symbols

Other controversies involving Confederate symbols have involved the right of individuals to display such symbols in workplaces and in educational settings.

In 1997, the North Carolina Court of Appeals held in Johnson v. Mayo Yarns that an employer could compel an employee to remove a Confederate flag decal from his toolbox and that the employer’s decision to discharge him for refusing to do so did not violate Johnson’s First Amendment rights.

In 2000 in West v. Derby Unified School District, the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a Kansas school district’s suspension of a student for drawing a Confederate flag on a piece of paper during math class. Because the school had acted under the auspices of a well-defined policy designed to prohibit racial harassment and to minimize disruption of the educational environment for other students, the court found that the policy did not limit protected speech. Other challenges to school policies have yielded similar rulings.

In Walker v. Tex Div., Sons of Confederate Veterans (2015), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Texas did not violate the First Amendment by refusing to allow a specialty license plate designed by the Sons of the Confederate Veterans and featuring the Confederate battle flag. The court ruled that specialty license plates are a form of government speech and thus immune from a free-speech challenge.

More recently, a federal district court ruled in Brown v. City of Tulsa (2023) that a police officer’s post of presidential candidate Donald Trump riding a lion with a Confederate flag in the background was a form of protected political expression. However, when the court applied the balancing test for public employees in Pickering-Connick, the court found in favor of the police department and city.

Similarly, in Patton v. Dodson (2023), a federal district court in Illinois upheld the removal of a tow truck operator from the city’s tow list because he displayed a large Confederate flag on his property where he sometimes towed cars.

In both these decisions, the federal district courts emphasized the government’s interest in dissociating itself from the Confederate flag as many people perceive it as offensive.

A number of institutions also have renamed buildings that referenced Southern Civil War figures, and some cities, most notably New Orleans, have removed statues and monuments to Confederate war heroes. Challenges to government’s removal of monuments are difficult under the free speech clause of the First Amendment because the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled in Pleasant Grove v. Summum (2009) that monuments are a form of government speech immune from a free-speech challenge.

This article first published in 2009 and was most recently updated in November 2023 by David L. Hudson Jr. The primary contributor, Sara L. Zeigler, is the dean of the College of Letters, Arts, and Social Sciences at Eastern Kentucky University.