According to the Attorney General’s Commission on Pornography (1986), Commonwealth v. Sharpless, 2 Serg. and Rawle 91 (1815), led to the first obscenity prosecution in the United States.

Judge cited “corruption of morals” in prosecuting obscenity

A Philadelphia jury had indicted Jesse Sharpless and others for corrupting youth by showing them a picture of a man and a woman in what was described as “an obscene, imprudent, and indecent posture.” Sharpless had argued that obscenity was not indictable, first, because the crime was not a common law offense — his lawyer argued that in England such prosecutions would have taken place in ecclesiastical courts that had no counterparts in the United States — and had not been done in public, and, second, because the charge had not been sufficiently precise in describing the offensive material in question. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court sustained the conviction.

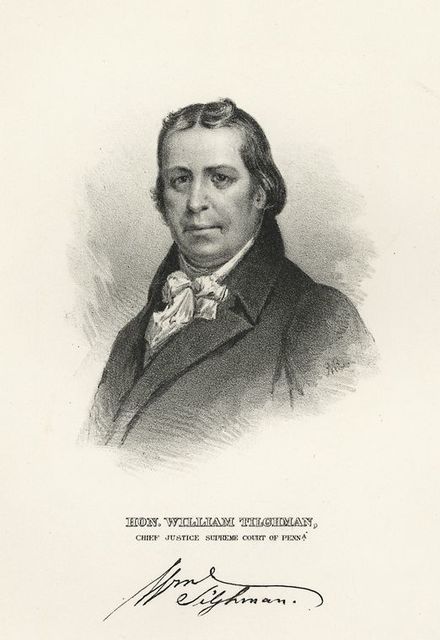

Chief Justice William Tilghman’s opinion cites English precedents relative to “corruption of morals” and notes that the “mischief” was equally bad whether done privately or publicly.

He further believed the indictment’s description of the material to be adequate. The description paid “respect to the chastity of our records.”

Courts should be “schools of morals”

In a concurring opinion, Justice Yeates (possibly Jaspar Yates) agreed, stating, “The corruption of the public mind in general, and debauching the manners of youth in particular by lewd and obscene pictures exhibited to view, must necessarily be attended with the most injurious consequences, and in such instances Courts of Justice are, or ought to be, the schools of morals.”

He too thought the offense punishable under the common law and agreed that further description of the picture in question would lead to further “wounding our eyes or ears.”

The U.S. Supreme Court would cite Sharpless in upholding a conviction for sending obscenity through the mail in Rosen v. United States (1896).

Similar to Sharpless, in Commonwealth v. Holmes (1821) the Massachusetts Supreme Court upheld the conviction of an individual who had shown a print from Fanny Hill to others. (Fanny Hill would later become the subject of the 1966 Supreme Court decision in Memoirs v. Massachusetts.)

Chief Justice Isaac Parker observed, as had the court in Sharpless, that requiring courts to print the offensive representation at issue would “require that the public itself should give permanency and notoriety to indecency, in order to punish it.”

By contrast, a Massachusetts court in Commonwealth v. Tarbox (1848) dismissed the conviction of a physician who had been indicted for printing a description of birth control devices. Accepting that “whenever a publication of this character is so obscene, as to render it improper that it should appear on the record; and, then, the statement of the contents may be omitted altogether, and a description thereof substitute,” the court found conviction inadequate without an “exact transcript” of the material.

John Vile is professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.