In Cantrell v. Forest City Publishing Co., 419 U.S. 245 (1974), the Supreme Court upheld a verdict against the Cleveland Plain Dealer, a newspaper of Forest City Publishing, for an article casting the plaintiff, Margaret Mae Cantrell, in false light.

Cantrell demonstrates one of the limitations to the freedom of the press.

Reporter interviewed Cantrell children about father’s death

Mrs. Cantrell’s husband had been among a number of people killed when the Silver Bridge across the Ohio River collapsed.

Five months later, a reporter and photographer with the Cleveland Plain Dealer visited the Cantrell home. Mrs. Cantrell was not there, so the reporter, Joseph Eszterhas, talked with the Cantrell children and the photographer took as many as 50 photographs during the visit.

Magazine article implied Mrs. Cantrell was present for interview

In a story that appeared on Aug. 4, 1968, in the paper’s Sunday magazine, Eszterhas emphasized the children’s “old clothes and poor condition of the Cantrell home… Margaret Cantrell will talk neither about what happened nor about how they are doing. She wears the same mask of non-expression she wore at the funeral. She is a proud woman. She says after it happened, the people in town offered to help them out with money and they refused to take it” (Teeter and Loving 2004: 377).

A U.S. district court allowed Mrs. Cantrell to collect $60,000 for proving that the newspaper showed a reckless disregard for the truth in publishing the story and for implying that she was present during the interview with her children.

Court said article had ‘calculated falsehoods’

Writing for the Supreme Court, Justice Potter Stewart noted the court’s agreement with the district court — which had asked the jury to hold the magazine liable for false statements if the jury found evidence of false or reckless disregard of the truth — but disagreement with the court of appeals decision concluding that no evidence existed of knowledge of inaccuracies in the article.

Stewart found sufficient evidence of what the Court considered “calculated falsehoods” in the article, especially the implication that Mrs. Cantrell was present during the interview. Justice William O. Douglas dissented because he believed that the First Amendment granted the press broader leeway in covering issues like this, which he considered to be “matters of public impact.”

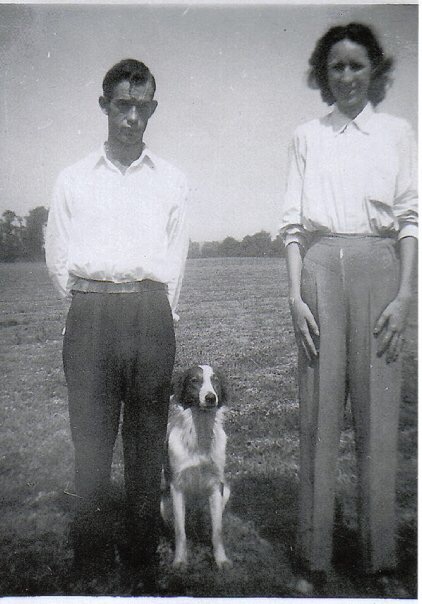

After Melvin Cantrell died in the Silver Bridge collapse, a news reporter visited his home and interviewed the children. Margaret Cantrell was not present, but the news reporter implied she was and attributed comments to her. The Supreme Court upheld a verdict against the newspaper for disregard for the truth. (Photo provided by Mrs. Cantrell’s granddaughter, Diane Mitchell.)

False light cases raise controversial First Amendment issues

The tort of false light — or putting a plaintiff in a false light — is the most controversial of the four elements in the law of privacy; some state courts do not recognize it.

Although some view false light as a deliberate distortion of the truth (Pember and Calvert 2004), mostly for the purposes of drama, others, while acknowledging that certain speech may put a plaintiff in a false light, think that such speech may not necessarily be considered defamatory by the public (Teeter and Loving 2004).

Courts approach “false light” on case-by-case basis

The courts approach this issue on a case-by-case basis, but generally, actions susceptible to false light are highly offensive to a “reasonable” person and require presentation in a publication or broadcast to become actionable (Zelezny 2004).

Television programming, especially docudramas and motion pictures, are especially vulnerable to this type of offense. A potential safeguard against fictionalization includes purchasing the rights to a story from the actual people involved, by which they forfeit their right to sue in the event that they are not pleased with the way they are portrayed.

This article was originally published in 2009. John Omachonu, Ph.D., is an educator, broadcast media practitioner, and teacher, who for more than two decades, taught college-level courses in mass media law and ethics. He is committed to the tenets, principles and practices of the First Amendment.