Byron Raymond White (1917–2002) served as an associate justice on the Supreme Court for more than 30 years, from 1962 to 1993.

White had a diverse early career

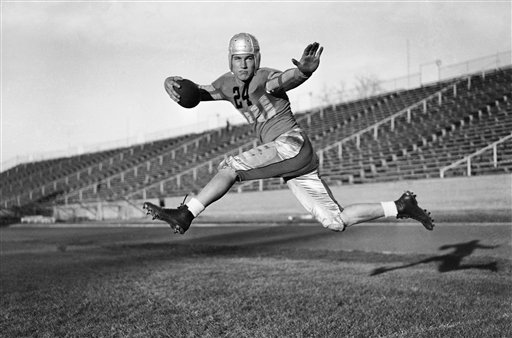

Byron White received his undergraduate degree from and was an All-American football player at the University of Colorado; he then won a Rhodes scholarship to Oxford, played professional football, and served as an intelligence officer in the U.S. Navy during World War II.

After the war, White completed his legal studies at Yale University and then clerked for Chief Justice Frederick M. Vinson of the Supreme Court. After his clerkship, he entered private law practice in Denver. During the Kennedy campaign for the White House, White ran the Colorado Committee for Kennedy and was asked to serve as deputy attorney general under Robert Kennedy in the U.S. Justice Department.

After two years in the Justice Department, President John F. Kennedy nominated White to the U.S. Supreme Court.

White was a disappointment to some because of his views on individual rights

Upon joining the Court, White confounded many observers because his jurisprudence appeared to lack a comprehensive philosophy, focusing more upon case-by-case specifics and less on constructing a clear, consistent theory (Abraham 1999).

For many liberals who had hoped that a Kennedy appointee would join the Warren Court’s rights revolution, White was a huge disappointment in regard to his views on certain minority or individual rights — see White’s dissents in Miranda v. Arizona (1966), involving the rights of criminal defendants, and Roe v. Wade (1973), involving abortion, and his majority opinion in Bowers v. Hardwick (1986), upholding a state anti-sodomy law.

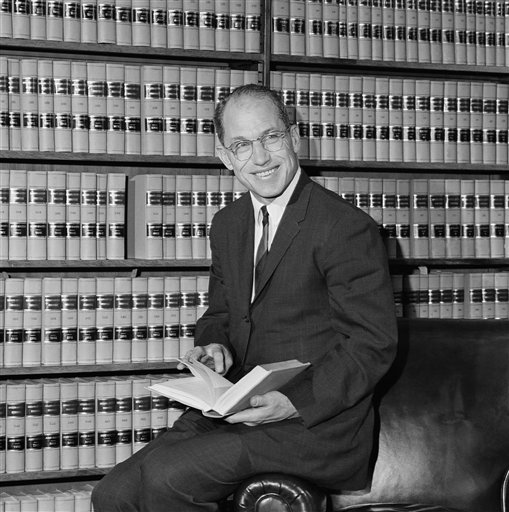

Supreme Court Justice Byron White was not known as a friend of First Amendment rights. For example, he refused to grant constitutional protection to journalists who claimed they should have the privilege to not divulge sources to a grand jury. White, who played football at Colorado University and professionally, poses in this 1937 photo. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press.)

White not a First Amendment friend

Regarding the First Amendment, White was hardly a favorite of the press.

For example, in 1969 White wrote the majority opinion in Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which upheld the constitutionality of the FCC’s fairness doctrine requiring broadcasters to offer time to reply to those who had been attacked or criticized on air.

White’s opinion stressed that the airwaves were a public good that the government could regulate, even if it meant that the activities of the broadcast press were restricted.

In Branzburg v. Hayes (1972), White refused to grant constitutional protection to journalists who claimed they should have the privilege to not divulge sources to a grand jury. White was not convinced that the absence of such a journalist privilege would hamstring press operations, and as such felt the invention of another constitutional right was not warranted.

He angered the press further in 1978 with his majority opinion in Zurcher v. Stanford Daily. In Zurcher White held that the freedom of the press did not prohibit the government from executing searches of newsrooms per specific warrants.

As in previous rulings, White stated that the job for the courts was to balance competing interests, even if it meant at times that rights found in the Constitution were curtailed.

The next year, White’s opinion for the Court in Herbert v. Lando (1979) held that the First Amendment did not prohibit a discovery request for outtakes and other unpublished material in a libel suit.

A balancing approach to rights

White’s balancing approach to rights found in the First Amendment could also be seen in his votes and writings on the political speech rights of government workers.

For example, in United States Civil Service Commission v. National Association of Letter Carriers (1973), White’s majority opinion upheld the constitutionality of the Hatch Act, which prohibits government officials from forcing staffers to engage in political activities on their superiors’ behalf but which also restricts the political speech activities of government employees.

Likewise, in Connick v. Myers (1983), the Court ruled against the government worker, and White’s majority opinion emphasized that when reviewing whether the government could restrict the political speech rights of its workers, the Court had to balance the rights of public employees to comment upon matters of public concern versus the interests of the government to have an efficient provision of services, as per Pickering v. Board of Education (1968).

He also wrote the opinion for the Court in Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier (1988), which limited public students’ First Amendment rights for school-sponsored speech.

This article was originally published in 2009. Dr. John M. Aughenbaugh is an assistant professor in the Political Science Department at Virginia Commonwealth University. His teaching and research interests focus generally on U.S. public law (Constitutional Law and Administrative Law), judicial politics, and public policy & administration.