Bumper stickers remain a ready outlet for citizens to express themselves on a variety of topics — political candidates, environmental causes, religion, sports teams, just about any subject imaginable. They also present intriguing fre expression issues when the government decides to prosecute the displayer of an offensive bumper sticker.

Some state criminalize obscene bumper stickers

A few states have statutes that criminalize the display of obscene bumper stickers. For example:

- A Tennessee law prohibits the display of “obscene or patently offensive bumper stickers.”

- An Alabama law prohibits bumper stickers that depict “obscene language of sexual or excretory activities.”

- And a South Carolina law prohibits the display of any obscene or “indecent” bumper sticker. Violators may be subject to a $200 fine.

The constitutionality of criminalizing bumper stickers remains in serious doubt, because it is difficult to imagine a bumper sticker that would actually meets the legal definition of obscenity.

In 2021, Columbia County, Florida, sheriff’s deputies arrested a man for a bumper sticker that said “I eat ass.” Prosecutors concluded that the obscenity standard had not been met and dismissed the charges. In a subsequent lawsuit against the officers for alleged First and Fourth Amendment violations, U.S. District Judge Marcia Morales Howard of the Middle District of Florida ruled that the officers could not be held liable because the stop was “arguably justified under Florida’s obscenity law.”

Profane bumper stickers protected

Several courts have invalidated convictions based on the display of profane bumper stickers. For example, in Cunningham v. State (1991) the Georgia Supreme Court reversed the conviction of a man whose vehicle displayed a bumper sticker that said “Shit Happens.”

The court concluded that “the provision regulating profane words on bumper stickers reaches a substantial amount of constitutionally protected speech and unconstitutionally restricts freedom of expression” under the First Amendment.

Similarly, a federal district court in Alabama reversed the conviction of a truck driver whose vehicle bore the bumper sticker “How’s My Driving? Call 1-800-EAT SHIT!” Ruling in Baker v. Glover (1991), the court held that the bumper sticker was protected under the First Amendment “because it has serious literary and political value.”

The judge wrote: “Although surely not a likely candidate for a literary prize, Baker’s bumper sticker has serious literary value as a parody of stickers, such as ‘How’s My Driving? Call 1-800-2-ADVISE. . . . Baker’s sticker also has political value as a protest against the ‘Big Brother’ mentality promoted by such other bumper stickers that urge the public to report the indiscretions of truck drivers.”

In Louisiana, an appeals court reversed the conviction of a former deputy for disturbing the peace — his truck displayed a bumper sticker that said, “Fuck Charles Foti, Jr.,” the sheriff of Orleans parish, for whom Meyers had previously worked.

The state appeals court reasoned in Louisiana v. Meyers (1984) that the conviction could not stand in light of the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Cohen v. California (1971), which invalidated the conviction of a man who wore in a California courthouse a jacket bearing the words “Fuck the Draft.”

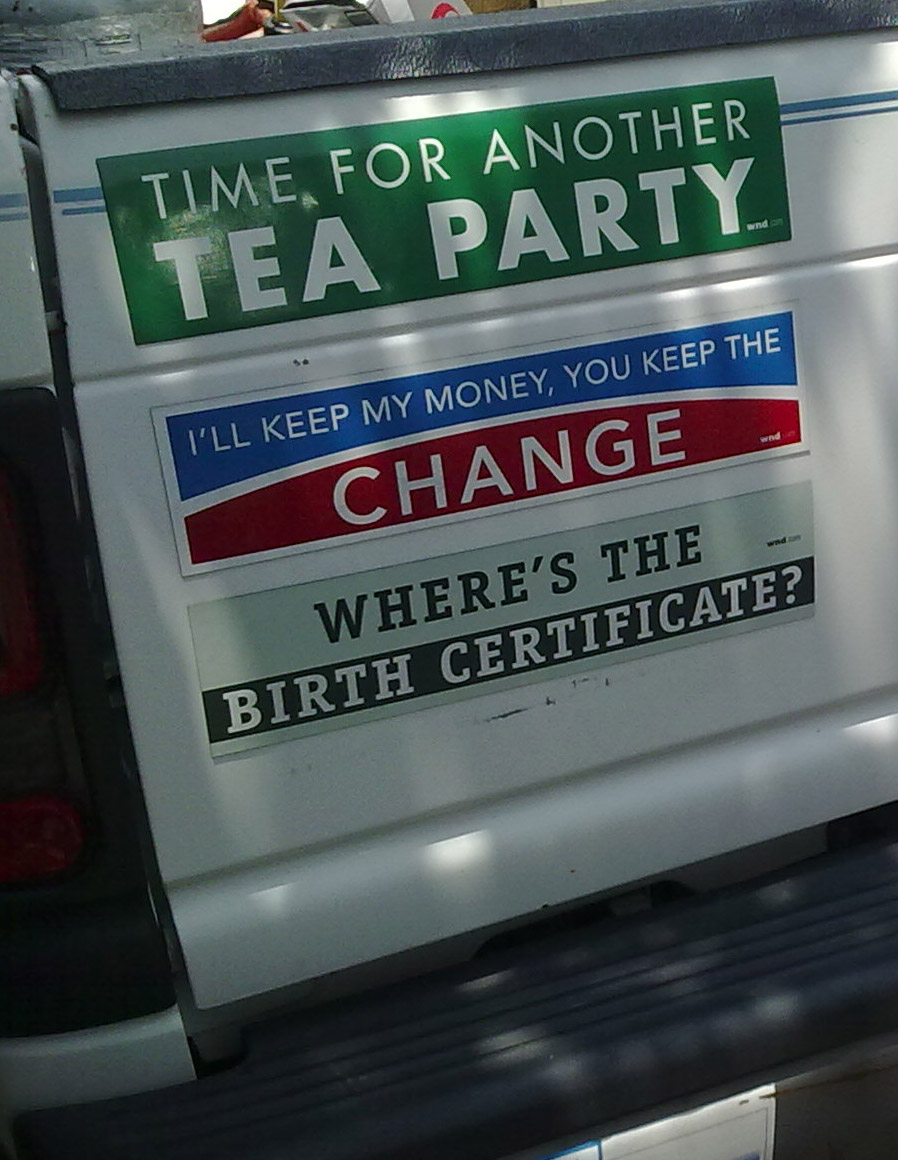

The outcome in bumper sticker cases becomes less clear when the possessor of a bumper sticker is a public employee or member of the armed forces. Members of the armed forces and civilians on military bases may well have little First Amendment protection from a bumper sticker regulation. In this photo, bumper stickers are displayed on the back of a personally owned vehicle at Minot Air Force Base, N.D., March 16, 2017. Airmen may have bumper stickers on their POVs as long as they don’t discredit the Air Force. (U.S. Air Force photo/Airman 1st Class Alyssa M. Akers, public domain)

For public employees, protection for bumper stickers is less clear

The outcome becomes less clear when the possessor of a bumper sticker is a public employee or member of the armed forces. In Connealy v. Walsh (1976), a federal district court in Missouri ruled that a juvenile court social worker could be fired for refusing to remove a political bumper sticker from her car. The court noted that a partisan political bumper sticker could adversely affect the social worker’s efficiency.

In Williams v. McKee (2016), the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that a detention officer with a Colorado sheriff’s officer could be fired for refusing to remove a bumper sticker on his vehicle that read: “Still voting Democrat? You’re so stupid.”

The appeals court reasoned that the bumper sticker contained “language [that] could easily spark conflict with fellow employees or the public.”

However, other courts have sided with public employees who have challenged restrictions on bumper stickers.

In Fire Fighters Association v. Barry (1990), a federal district court in the District of Columbia invalidated the fire department’s regulation on bumper stickers, finding that the regulation was overbroad and the viewpoint discriminatory. The court reasoned that the regulation discriminated on the basis of viewpoint because it punished only those who displayed bumper stickers critical of the employer.

In Goodman v. Kansas City (1995), a federal district court in Missouri invalidated a regulation that prohibited city employees from displaying political bumper stickers on their vehicles. The court concluded that “the right to express oneself about issues and candidates at election time is an essential part of our constitutional democracy.”

Kentucky has a statute that protects the rights of public employees to “place political bumper stickers on their privately owned vehicles.” Illinois has a law that protects the rights of university faculty and staff members to display partisan political bumper stickers on their vehicles.

Armed forces have little First Amendment protection from bumper sticker regulation

Members of the armed forces and civilians on military bases may well have little First Amendment protection from a bumper sticker regulation.

In Ethredge v. Hail (1995), the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld an air force administrative order that barred bumper stickers that “embarrass or disparage” the president. Jesse Ethredge, a civilian aircraft mechanic on an air force base, unsuccessfully challenged the policy in federal court. The Eleventh Circuit granted great deference to military authorities and reasoned that the regulation furthered the military’s interests in maintaining good order and discipline.

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.