The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (BCRA) established additional campaign contribution and spending rules in federal elections and set new standards for electioneering communications. Such rules continue to be controversial to the extent that regulations of contributions and expenditures limit freedom of speech and press.

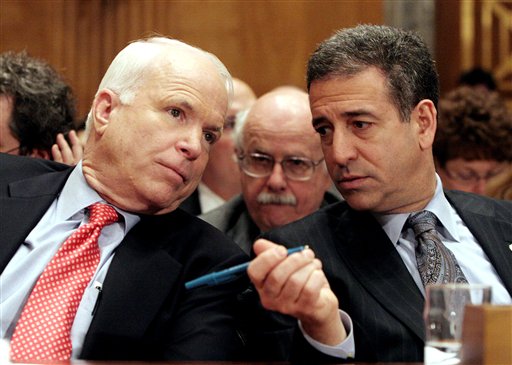

Controversial law introduced by McCain and Feingold

Introduced in 1997 by Senators John McCain, R-Ariz., and Russ Feingold, D-Wis., the BCRA sought to redress shortcomings of the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 (FECA) and the abusive campaign fundraising practices of the 1996 federal elections.

Supporters of the BCRA sought to preserve the integrity of the U.S. electoral system, reduce the role of money and corruption in politics, and give ordinary Americans an opportunity to express political ideas without being overshadowed by megacontributors. Critics continued to charge that by limiting contributions and expenditures, the law was limiting First Amendment freedoms.

BCRA prohibits ‘soft money’ donations

One of the most significant campaign finance regulations introduced by the BCRA was that national political party committees can no longer receive “soft money”— that is, unlimited donations to political parties from individuals, unions, or organizations — for federal elections. The act also prohibits federal candidates and officeholders from raising, receiving, or spending soft money for local, state, and federal political parties or in federal elections.

Furthermore, the BCRA forbids soft money expenditures for “party-building activities,” such as voter registration and get-out-the-vote efforts, linked to a specific federal candidate. However, corporations, unions, and state and local party committees may use contributions of up to $10,000 per donor annually for get-out-the-vote efforts on behalf of state and local candidates if state law permits.

These voter registration and get-out-the-vote activities funded by soft money may not be allocated to federal candidates, and, under these guidelines, a state party committee cannot solicit the money for use in other states. Each political party or local party committee must raise its own get-out-the-vote contributions. Part of get-out-the-vote expenditures must include “hard money,” or direct contributions to political candidates that are subject to specified limits and disclosure requirements.

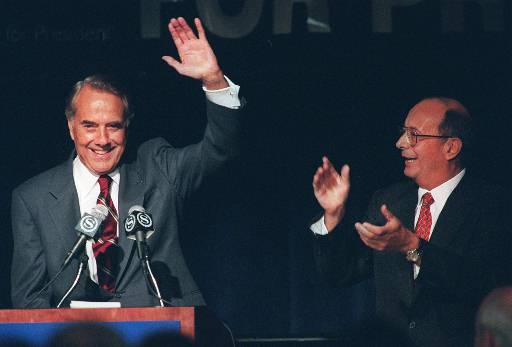

The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act was introduced in 1997 by Senators John McCain, R-Ariz., and Russ Feingold, D-Wis., the BCRA sought to redress the abusive campaign fund-raising practices of the 1996 federal elections. As part of the 1996 presidential race, Republican presidential candidate Senator Bob Dole (R-Kan.) waves from the podium as Senator Alfonse D’Amato (R-N.Y.) applauds at a Dole For President fundraising dinner in New York Monday, Oct. 16, 1995. (AP Photo/Adam Nadel, used with permission from the Associated Press)

BCRA regulates electioneering communications

Another area regulated by the BCRA is issue-advocacy advertisements and electioneering communications. Under the BCRA, electioneering communication is defined as broadcast, cable, and satellite advertisements that refer to specific candidates within 60 days of the general election or 30 days of primary and that target 50,000 or more persons in the congressional district or state where the election is being held. Issue-advocacy ads are supposed to address specific issues (such as pro-gun control or anti-gun control) rather than specific candidates.

In practice, however, these ads have been used to spend unlimited amounts of money on attack ads aimed at certain candidates. To ensure that issue advocacy ads remain genuine and to address electioneering communications, the BCRA requires any state or local party running ads that promote, support, attack, or oppose any federal candidate for federal office to fund the ads with hard money.

The BCRA forbids the use, within 60 days of a general election or 30 days of a primary, of corporate or union treasury monies for electioneering advertisements that mention a federal candidate and are aimed at the candidate’s voting populations. Unions and corporate entities can still fund these broadcasts through their political action committees (PACs).

BCRA increased individual contribution limits

To compensate for the anticipated loss in revenues from a soft-money ban in federal elections, the BCRA increased individual contribution limits to candidates and political parties and indexed them to rising campaign costs.

For example, instead of a limit of $1,000, individuals could contribute $2,000 per election (primary, general, and runoff) to candidates for any federal office.

The former $20,000 limit was increased to $25,000 per year that an individual could give to national political party committee up to an aggregate of $57,500 per cycle to all national party committees and PACs. Other limits were also increased and as years have passed, those contribution limits in federal races have risen.

The BCRA also set variable contribution limits for congressional candidates facing self-financed, wealthy candidates. In Senate and House campaigns, a sliding scale was established to raise the amount of individual contributions allowed when self-financed candidates spend a certain amount of personal money. The complicated formula was devised to counter the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Buckley v. Valeo (1976), which allowed candidates to spend unlimited amounts of their own money.

One of the most significant campaign finance regulations introduced by the BCRA was that national political party committees can no longer receive “soft money”—that is, unlimited donations to political parties from individuals, unions, or organizations for “party building” in federal elections. In this photo, Rep. Christopher Shays, R-Conn., discusses campaign finance reform as demonstrators wave signs calling for a ban on soft money, during a rally in front of historic Faneuil Hall in Boston, Monday morning, July 9, 2001. Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., right, joined him at the rally. (AP Photo/Angela Rowlings)

Legal challenges have overturned some parts

Implementation of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act has been subject to legal challenges. The first was McConnell v. Federal Election Commission (2003), a case consolidated by the lower federal courts from 12 lawsuits brought by more than eighty plaintiffs challenging thirteen provisions.

Opponents of the BCRA believe that the act illegally prevents officeholders from helping their state and local political party organizations, that it unconstitutionally restricts speech 60 days before a general election, and that it unreasonably infringes on political party fundraising. The U.S. Supreme Court, largely disagreeing with the opponents, upheld the act’s soft money and electioneering communications provisions, but it struck down the prohibition on minors making political contributions and the requirement that political parties choose between independent expenditures and coordinated expenditures on behalf of a candidate.

The decision in McDonnell was highly fractured, with several justices writing separately. In his partial concurrence and dissent, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote that “the Court today upholds what can only be described as the most significant abridgment of the freedoms of speech and association since the Civil War.” Thomas repeated his calls for the Court to overrule Buckley v. Valeo.

FEC came under attack for rules implementing BCRA

Later, the Federal Election Commission (FEC) came under sharp attack, and in Shays v. FEC (D.D.C. 2004) a federal appellate court struck down many of the FEC rules for implementing the BCRA as a violation of the law’s spirit. In Federal Election Commission v. Wisconsin Right to Life, Inc. (2007), the electioneering communication provisions of the law were challenged again. The Supreme Court held in a per curiam opinion that these provisions in specific instances could possibly violate the First Amendment rights to free speech and to petition the government. This ruling, along with Shays, reopens the issue of how to implement the law.

In 2022, the Supreme Court invalidated a provision in the law that prohibited a campaign committee from repaying a personal loan made to the campaign by the candidate with post-election contributions. The court in Federal Election Commission v. Cruz said that law had the effect of restricting candidates from financing campaigns, burdening political speech. A dissent, authored by Justice Elena Kagan, argued that the law was meant to discourage a quid pro quo of a contributor giving to a winning candidate after the election in exchange for influence.

BCRA does not close all loopholes

Although the BCRA takes steps to regulate money in federal elections, it does not close all the loopholes, and many electioneering activities and communications are left unregulated, including interest groups’ independent expenditures and issue advocacy ads before the 60- and 30-day windows.

The BCRA also does not regulate voter guides, direct mail, Internet communications, and telephone-bank calls. In campaign finance reform, every new law creates new loopholes and new controversies. The Bipartisan Campaign Finance Reform Act, like the Federal Election Campaign Act before it, will probably be amended by Congress and revisited by the courts for years to come.

This article was originally published in 2009. Ruth Ann Strickland was a professor at Appalachian State University.