In Associated Press v. Walker, 388 U.S. 130 (1967), the Supreme Court ruled that public figures should be treated differently from public officials when they sue for libel. The Court ruled that they could recover damages under finding of highly unreasonable conduct by reporters and publishers.

This case, a companion to Curtis Publishing Company v. Butts, is notable for the extensive discussion and difficulty the justices had in reaching their decision.

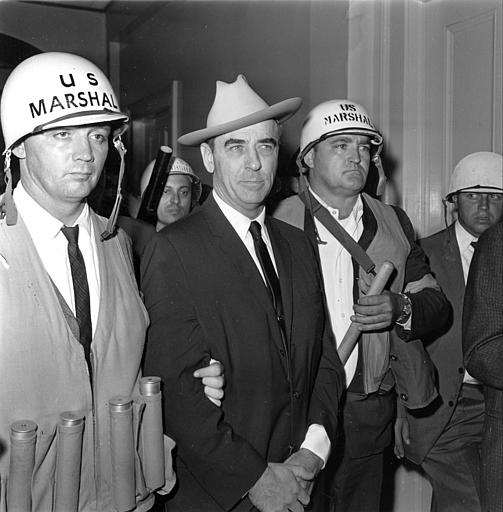

Former U.S. general sues after Associated Press reports he led a charge against marshals

Edwin Walker, a retired U.S. general, had been in charge of federal troops in the Little Rock, Arkansas, school desegregation confrontation in 1957.

Ten years later, he became engaged in the debate over desegregation at the University of Mississippi, attracting significant publicity for his statements against federal intervention; he even had a “friends of Walker” following.

A correspondent from the Associated Press (AP) was present when demonstrations turned violent on the night of September 30, 1962. He sent a dispatch, reporting that Walker “[a]ssumed command of the crowd” and led them in a charge against the U.S. marshals. That dispatch was then sent to newspapers subscribing to AP services.

Walker sued for libel. The trial court and Texas Court of Civil Appeals awarded compensatory damages to him, because AP could not prove that its published statements were true, but denied punitive damages because Walker could not prove malice on the part of the news organization.

Public figures must show “highly unreasonable conduct” that departed from normal standards

Justice John Marshall Harlan II’s opinion for the Court commanded four votes plus concurrences from every other justice, overturning Walker’s award of compensatory damages.

The Court first concluded that Walker was a “public figure,” given “his personal activity amounting to a thrusting of his personality into the ‘vortex’ of an important public controversy.”

He also “commanded sufficient access to the means of counterargument to be able to expose through discussion the falsehood and fallacies of the defamatory statements.” Harlan reasoned, however, that public figures could recover damages for false defamatory statements only “on a showing of highly unreasonable conduct constituting an extreme departure from the standards of investigation and reporting ordinarily adhered to by responsible publishers.”

Because the reporter was reliable and the story “hot news,” the Court found AP’s conduct reasonable.

Warren believed actual malice standard should be applied to cases of public figures

Chief Justice Earl Warren concurred, but felt that the doctrine established in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964) requiring actual malice should be extended to public figures as well as to public officials.

The Court would adopt Warren’s view 10 years later in Gertz v. Robert Welch (1974), but the debate would continue on what constituted a person being a “public figure.”

Justices Hugo L. Black and William O. Douglas concurred in Walker, agreeing with the result and reasoning of Justice Warren but asserting that Sullivan provided too little protection for the press.

This article was originally published in 2009. Geoffrey P. Hull is a retired Professor Emeritus from Middle Tennessee State University.