Four justices of the Supreme Court, led by Justice William J. Brennan Jr., concluded in A Quantity of Books v. Kansas, 378 U.S. 205 (1964), that a procedure used to seize and impound 1,715 books prior to an obscenity hearing was constitutionally insufficient because it did not safeguard against the suppression of nonobscene books. The Court’s plurality decision reversed a Kansas Supreme Court judgment upholding the seizure and destruction of the books.

Authorities confiscated allegedly obscene books before a hearing

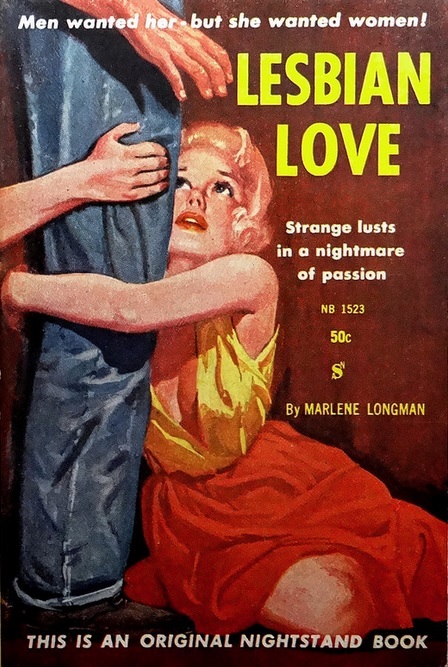

Authorities had confiscated the books under a Kansas statute permitting the seizure and destruction of obscene materials. Although the statute only required the filing of an information — a state alternative to a grand jury indictment — identifying the presence of an obscene book, the state’s attorney general filed an information identifying 59 specific novels and provided the court with copies of seven of them.

In an ex parte inquiry, the district judge “scrutinized” the seven novels, determined them to be obscene, and issued a warrant authorizing the seizure of all 59 titles. When authorities executed the warrant, only 31 of the titles (totaling 1,715 books) were found and impounded.

Kansas argued book seizure procedure was constitutional

The business from which the novels were seized filed a motion to quash the information and the warrant, arguing that it should have been afforded a hearing on the issue of whether the novels were obscene before the warrant’s execution. The district court denied the motion and ordered the sheriff to destroy the books. The Kansas Supreme Court held that the procedures met constitutional requirements and affirmed the district court’s order.

The attorney general argued that the procedure followed was necessary under the Supreme Court’s decision in Marcus v. Search Warrant (1961). That case involved the seizure of obscene materials under a Missouri statute similar to that of Kansas. In Marcus, the warrant had been issued on a complaint lacking examples of the materials or any specific description of them, and it gave the police virtually unlimited authority to seize publications they deemed obscene.

Court said book seizure procedure prior to obscenity hearing violated the First Amendment

The Supreme Court held, however, that books seized in this manner, even if actually obscene, could not be destroyed because the process used to seize them lacked constitutional safeguards to prevent the suppression of nonobscene materials. The Court cited Kingsley Books, Inc. v. Brown (1957), in which it upheld a similar New York procedure that postponed all injunctive relief until an adversary proceeding on the issue of obscenity could be held.

Based on this precedent, the Court concluded that the Kansas procedure was unconstitutional because it did not provide a hearing on the issue of obscenity before seizing the books, pointing out that if seizures precede such hearings, “there is danger of abridgement of the right of the public in a free society to unobstructed circulation of nonobscene books.”

Justice John Marshall Harlan II authored a dissent, joined by Justice Tom C. Clark, indicating that he saw adequate evidence to find the materials to be obscene and that an adversary hearing had not been necessary.

This article was originally published in 2009. Emilie S. Kraft is an administrative law judge in Birmingham, Alabama.