Once dismissed as a fad, rap music has become a cultural mainstay and a billion dollar industry. The musical genre, a segment of which often features a hard-core assessment of societal woes in the inner cities, has come under threats of censorship through the years in a variety of contexts. Some government officials and others charged that certain rap lyrics were incendiary and contributed to violence. Case in point, the Federal Bureau of Investigation sent letters in 1989 to Priority Records about the rap group N.W.A.’s hit song Fuck Tha Police.

Many other rappers have been threatened through the years with either obscenity charges or censorship efforts, including such rap pioneers as Ice-T and Too Short. Rap lyrics became the subject of a U.S. Supreme Court case, Elonis v. United States (2015), when the Court evaluated whether a man committed a true threat when he posted rap lyrics that allegedly threatened his ex-wife and others. However, the Court did not directly address the artistic merits, or lack thereof, of Elonis’ lyrics in issuing its decision.

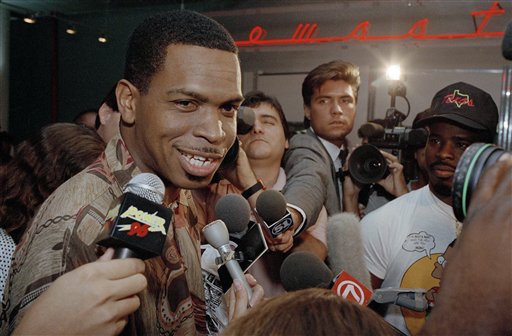

In 1990, a federal district court judge declared lyrics from “As Nasty As They Wanna Be” by rap group 2 Live Crew to be obscene, using the Supreme Court’s Miller Test. However, the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed, explaining that the plaintiffs had submitted expert testimony that the album contained serious artistic value — a contention not refuted by the sheriff by any expert testimony or other evidence other than a tape recording of the album.Pictured here is Luther Campbell, aka Luke Skyywalker, lead singer of 2 Live Crew in Miami airport in 1990. (AP Photo/Chris O’Meara)

Rap music not always obscene

In a high profile case, Broward County, Florida sheriff Nick Navarro prosecuted record store owners who sold the rap group 2 Live Crew’s album As Nasty As They Wanna Be, which contained many tracks filled with profanity and sexually laced language. Navarro believed that the album constituted obscenity.

Skyywalker Records, the record company of 2 Live Crew’s lead performer Luther Campbell, and the four members of the group filed a lawsuit in federal court, seeking a judicial declaration that their album was not obscene and that the actions of Navarro imposed an unconstitutional prior restraint on expression.

A federal district court judge declared the record obscene in Skyywalker Records v. Navarro (1990), applying the Miller Test from the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision Miller v. California (1973). However, the plaintiffs appealed to the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, which reversed in Luke Records v. Navarro (1992). The appeals court explained that the plaintiffs had submitted expert testimony that the album contained serious artistic value – a contention not refuted by the sheriff by any expert testimony or other evidence other than a tape recording of the album.

“A work cannot be held obscene unless each element of the Miller test has been met,” the appeals court wrote. “We reject the argument that simply by listening to this musical work, the judge could determine that it had no serious artistic value.”

Does rap music incite violence?

In 1997, family members of a slain state trooper contended that rap star Tupac Shakur’s album “2Pacalypse” contributed to a Texas trooper’s death because the killer was listening to it before he shot the trooper. The family contended the music incited imminent lawless action, but the court disagreed. “At worst, Shakur’s intent was to cause violence some time after the listener considered Shakur’s message. The First Amendment protects such advocacy.” Pictured is Tupac Shakur in 1994. (AP Photo/Bebeto Matthews)

Another criticism of rap music, particularly the so-called “gangsta rap” genre, is that it can incite imminent lawless action. That was the essence of the argument filed by the attorneys for three family members of a slain Texas state trooper in Davidson v. Time Warner (1997). The state trooper was killed by Ronald Howard, who was listening to the rap album by Tupac Shakur entitled 2Pacalypse Now.

The plaintiffs’ contended that Time Warner, the producer of the album, was legally responsible for the death of Trooper Davidson, because the anti-police lyrics in 2Pacalypse Now caused Howard to kill the trooper. The plaintiffs argued that the music constituted incitement to imminent lawless action under Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969). They cited Tupac Shakur’s claim that his music was “revolutionary.” Time Warner contended that the music was a form of protected expression under the First Amendment.

A federal district court in Texas sided with Time Warner and ruled that the album was protected by the First Amendment. Regarding the incitement allegation, the court explained: “Calling one’s music revolutionary does not, by itself, mean that Shakur intended his music to produce imminent lawless conduct. At worst, Shakur’s intent was to cause violence some time after the listener considered Shakur’s message. The First Amendment protects such advocacy.”

Use of rap music videos as evidence in crime

There is a growing number of criminal cases involving the prosecutorial use of rap music as evidence in trials. Legal commentators Donald F. Tibbs and Shelly Chauncy write: “There is a new form of policing and prosecutorial decisionmaking that is as dangerous as it is unconstitutional. It involves prosecutors using amateur rap music videos – sometimes with scant additional evidence – to prosecute and convict Black men.”

Prosecutors often seek to introduce rap videos into evidence because they show the existence of a criminal enterprise, association with other members, familiarity with firearms, and a motive to commit certain crimes. Defendants often counter that rap music videos are speech on matters of public concern, namely commentaries on urban life, the war on drugs, and the lack of hope in the inner city. However, courts often quote the hate crime case Wisconsin v. Mitchell (1993) for the proposition that the First Amendment “does not prohibit the evidentiary use of speech to establish the elements of a crime or to prove motive or intent.”

For example, in U.S. v. Herron (2014), a federal district court in New York rejected the First Amendment arguments of Ronald Herron, a.k.a “Ra Diggs”, who sought to prohibit prosecutors from introducing rap music and rap-related videos. The court reasoned that the videos “have bearing on issues in this case, i.e., charges of racketeering, racketeering conspiracy, murder in-aid-of racketeering, firearms offenses, etc.”

In Atlanta in 2023, a judge used this reasoning to rule that rap lyrics could be used in a case against rapper Young Thug who is charged, along with others, of anti-gang and anti-racketeering laws. The prosecutor argued that the lyrics refer to the criminal act or the criminal intent related to the charges.

Contrast that reasoning with the New Jersey Supreme Court in State v. Skinner (2014). The state high court ruled that the introduction of graphic rap lyrics into a murder trial was unduly prejudicial evidence that outweighed any potential relevancy of the material. While the court decided the case on evidence grounds, as opposed to the First Amendment, the state high court wrote: “Fictional forms of inflammatory self-expression, such as poems, musical compositions, and other like writings about bad acts, wrongful acts, or crimes, are not properly evidential unless the writing reveals a strong nexus between the specific details of the artistic composition and the circumstances of the underlying offense for which a person is charged, and the probative value of that evidence outweighs its apparent prejudicial impact.”

Rap music as threats or substantially disruptive in student cases

Rap videos and lyrics have been the subject of many free-speech disputes involving public school students and discipline by school officials. In Bell v. Itawamba County Sch. Bd. (2015), the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that public school officials could discipline student Taylor Bell, whose rap persona was “T-Bizzle,” for his rap music video that he made off campus after learning that two white teachers allegedly had sexually harassed several Black students.

Bell contended that his off-campus artistic expression was protected speech under the First Amendment. However, school officials said that the video was a form of an unprotected true threat and substantially disrupted school activities under the seminal standard from Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969). The 5th Circuit majority reasoned that Bell’s recording was substantially disruptive, writing that “threatening, harassing, and intimidating a teacher impedes, if not destroys, the ability to teach.”

In Jones v. State (2002), the Arkansas Supreme Court upheld the delinquency adjudication of a student who was charged with making a terroristic threat toward a female student through rap lyrics. The student wrote the rap lyrics and handed it to the girl. The female student went to the school principal, who called the police.

After losing in the juvenile court, Jones appealed to the state high court. The state high court upheld his delinquency finding, reasoning that his lyrics were not protected by the First Amendment because they constituted a true threat.

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.