The Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 (FECA) regulated the financing of federal election campaigns (president, Senate, and House), including the money raised and spent by the candidates pursuing those offices and by the political parties.

Congress had already tried to regulate various aspects of campaign finance before FECA

FECA was preceded by laws regulating various aspects of federal election campaign finance:

- The Tillman Act of 1907 banned corporate contributions in federal elections.

- The Publicity Act of 1910, as amended in 1911, required disclosure by campaign committees and limited campaign spending, but the limits were struck down in Newberry v. United States (1921).

- The Federal Corrupt Practices Act of 1925 imposed additional disclosure requirements.

- Amendments passed in 1940 to the Hatch Act of 1939 limited contributions to candidates and to national party committees and imposed spending limits on party committees.

- And in 1947 the Taft-Hartley Act outlawed labor union contributions and purported to restrict corporate and labor spending on federal elections as well. The spending limits were largely ineffective, however, because they applied only to party committee spending and could easily be evaded. The disclosure requirements were often ignored in the absence of any meaningful enforcement mechanism.

FECA was extensively amended after Watergate scandal

In 1971 Congress passed FECA, which limited the amount candidates could contribute to their own campaigns, limited the amount that a federal campaign could spend on paid advertising, and expanded disclosure requirements. The new law went into effect in the 1972 presidential election, but it was overshadowed by the Watergate scandal, which led to the first and only resignation of a U.S. president, Richard M. Nixon, in 1974. The various investigations brought to light numerous campaign-finance abuses, including illegal contributions from corporations, cash contributions, hidden funds controlled by the Nixon reelection committee, and favors extended to donors in exchange for large contributions.

In the wake of the scandal, in 1974 Congress enacted extensive amendments to FECA. These amendments limited to $1,000 per election the amount an individual could contribute to any federal campaign and introduced limits on the amount an individual could contribute to a political party or political committee and on the amount a political committee could contribute to a candidate ($5,000 per election).

The 1974 amendments also imposed a limit of $1,000 per election on independent spending by an individual or group “relative to a clearly identified candidate.” In addition, they limited the amount candidates for federal office could spend on their own campaigns and the amount parties could spend in support of candidates and on their national nominating conventions. The amendments established the Federal Election Commission (FEC) as an independent federal agency to enforce the regulatory regime, authorizing it to make rules and to investigate and impose civil penalties for violations of the law.

FECA allowed candidates receive grants to finance election campaigns

The 1974 law also established a system of voluntary public financing for presidential campaigns under which candidates seeking the nomination of the major parties could receive from the federal government funds matching the first $250 of each contribution from an individual, if the candidates agreed to limit their overall spending in seeking the nomination.

In the general election, major-party nominees could receive a substantial grant to finance their entire general election campaigns, if they agreed not to raise or spend any private contributions but to spend only the amount of the grant. In addition, the law strengthened public disclosure of campaign spending by requiring all political committees—not just campaigns or party organizations—to register and file regular reports with the FEC itemizing contributions to and expenditures by each committee.

FECA faced First Amendment court challenges

The constitutionality of the 1974 amendments was immediately challenged.

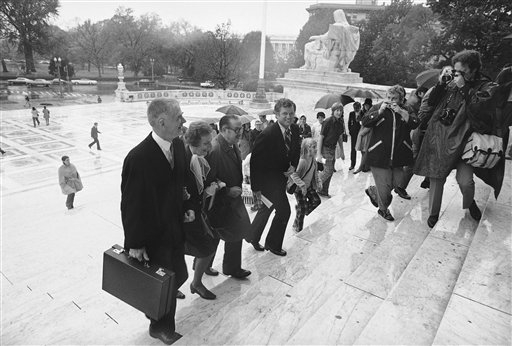

In Buckley v. Valeo (1976), the Supreme Court upheld the limits on contributions, the reporting and disclosure rules, and the system of voluntary public financing for presidential campaigns, but it struck down the limits on independent expenditures, the caps on campaign spending, and the limits on what candidates could contribute to their own campaigns.

As effectively rewritten by this decision, FECA served as the framework for regulating the financing of federal elections without major modification until passage of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act in 2002.

This article was originally published in 2009. Joe Sandler is a member of the firm Sandler Reiff Lamb Rosenstein & Birkenstock, P.C., in Washington, D.C.