In New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964), the Supreme Court reversed a libel damages judgment against The New York Times. The decision established the important principle that First Amendment guarantees of freedom of speech and press may protect libelous words about a public official in order to foster vigorous debate about government and public affairs.

This landmark decision constitutionalized libel law and arguably saved the civil rights movement.

City commissioner said newspaper ad about civil rights movement was libelous

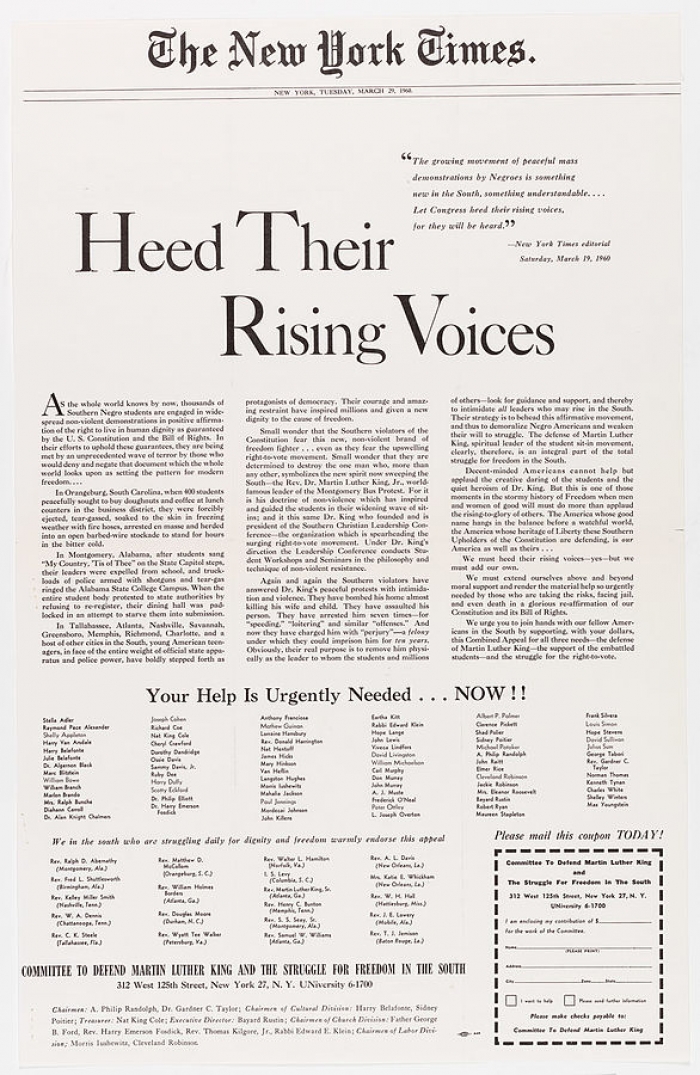

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan began as a lawsuit against the newspaper for mistakes in a full-page civil rights fundraising editorial advertisement in 1960 entitled “Heed Their Rising Voices.”

The advertisement, protesting the treatment of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. by Alabama law enforcement, carried the names of prominent civil rights activists, including actors, writers, ministers and other prominent Americans. The lawsuit was filed by L. B. Sullivan, an elected city commissioner in Montgomery, Alabama, whose duties included supervision of the local police. Under Alabama law, Sullivan only needed to prove that there were mistakes and that they likely harmed his reputation. A jury awarded him $500,000 in damages, an enormous sum at the time.

Supreme Court established actual malice standard

The Supreme Court unanimously reversed and dismissed the damage award. Writing for the majority, Justice William J. Brennan Jr. opined that “debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust and wide-open” and said that vehement criticism and even mistakes were part of the price a democratic society must pay for freedom. (The advertisement had gotten wrong the number of times Martin Luther King Jr. had been arrested in Alabama — four times instead of seven — and the details of police actions at Alabama State College.)

This is the New York Times advertisement that prompted a libel lawsuit by a city commissioner in Montgomery County who oversaw police. The Supreme Court reversed the libel judgment and created the concept of actual malice. Read text of ad.

To protect open discourse, the Court adopted the “actual malice” test, meaning that no public official could win damages for libel without proving that the statement was made “with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.”

The Court intended for this to be a high standard, one that public officials would have a hard time satisfying, one that required conduct by the news media that went beyond just negligence. Moreover, the Court made clear that the public official suing for damages had to prove the existence of actual malice “by convincing clarity.”

Having set the new high standard, the Court then established another important principle by immediately applying the new test to the facts of the case and declaring that there was insufficient evidence of “actual malice.” In other contexts, when the Supreme Court announces a new legal rule, the justices will send a case back to the lower courts to apply the new rule to the particular facts of the case. In New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, however, the Court established the principle of “de novo” review for free speech cases, meaning that the Supreme Court will determine for itself how legal principles apply to the facts of a case.

Ruling gave new First Amendment protections to publishers

The Court’s reversal of the damage award was unanimous, but Justices Hugo L. Black and Arthur J. Goldberg expressed separate views that the Court’s rule was too restrictive of free expression. Joined by Justice William O. Douglas, they said the right to discuss public affairs and to criticize government should be unconditional.

Prior to Sullivan, libel and defamation were entirely matters of state law, and the rules on when individuals could recover damages for injuries to their reputations varied widely. In 1964, however, the Supreme Court transformed the field of libel law from one governed by the laws of the states to one whose contours were determined by the First Amendment.

In subsequent rulings, the Court vastly expanded the protection for the news media to apply not just to lawsuits by public officials but also to claims by public figures — people in the news or public eye.

Press still subject to high costs of libel lawsuits, even when they win

The decision was a major First Amendment victory; yet, in less than two decades, there was criticism from opposite sides.

Some critics said the ruling made it too hard for individuals to undo damage to their reputations because it was difficult to prove actual malice. Other critics said the media were to exposed to the high cost of defending against lawsuits and appealing jury awards and too vulnerable to the intrusion on the newsgathering process caused by pretrial depositions and document discovery.

New York Times columnist Anthony Lewis wrote in 1983 that “it is not just judgments that worry publishers and reporters and others concerned with freedom of expression. It is the cost of defending libel actions: the cost not only in money but in time and in the psychological burden on editors and reporters.”

This criticism by the media of the impact of New York Times v. Sullivan has quieted in recent years. Over time, the federal appeals courts proved a reliable check on jury verdicts that seemed designed to punish the media without really satisfying the actual malice standard.

This article was originally published in 2009. Stephen Wermiel is a professor of practice at American University Washington College of Law, where he teaches constitutional law, First Amendment and a seminar on the workings of the Supreme Court. He writes a periodic column on SCOTUSblog aimed at explaining the Supreme Court to law students. He is co-author of Justice Brennan: Liberal Champion (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010) and The Progeny: Justice William J. Brennan’s Fight to Preserve the Legacy of New York Times v. Sullivan (ABA Publishing, 2014).