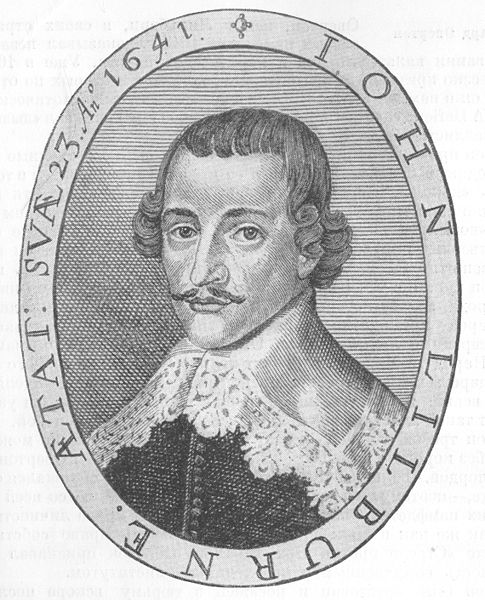

The Englishman John Lilburne (1615–1657), widely known as “Free-born John” during much of his adult life, was a prominent defender of religious liberties and free speech and a celebrated political prisoner.

Justice Black cited Lilburne’s influence on the constitutional framers

Supreme Court Justice Hugo L. Black cited the influence of Lilburne’s essays on the philosophies of U.S. constitutional framers in his dissent in Adamson v. California (1947). In a 1960 lecture at the New York University School of Law, Black cited a Lilburne essay as a source of principles both for early state constitutions and for the federal constitution. Lilburne had argued that a new English constitution needed to be legally superior to common statutes in order to promote continuity in government and to protect the free exercise of religion, speech, and press.

He was one of the leaders of the Leveller movement during the English Civil War opposing King Charles I, but fell out of favor with Oliver Cromwell and Parliament during the Protectorate when he accused that government of oppressing natural rights.

Lilburne refused to testify against himself

Lilburne gained national notoriety in 1638 when he became the first person before the Privy Council and the Star Chamber to refuse to swear an oath affirming he would tell the truth during his inquisition, on the grounds that no man should be compelled to testify against himself.

Charles I had granted the Star Council broad powers to punish those subversive to the crown, and the head of the Council, Archbishop William Laud, sentenced Lilburne to a public whipping, a £500 fine, and a prison sentence. As news of his refusal to take the oath and subsequent conviction spread throughout England, the public celebrated Lilburne as “Free-born John.” During his whipping, the executioner is reported to have said, “I have whipped many a Rogue before, but now I shall whip an honest man.”

During his initial imprisonment, Lilburne was held in solitary confinement. He still managed to write and to have published several tracts while he was being held, and dozens more after he was moved into the common yard, most of them attacking the court that had convicted him. After Charles I reconvened Parliament two and a half years after Lilburne was imprisoned, Oliver Cromwell secured Lilburne’s release.

Lilburne spoke out against the established Presbyterian church

Near the end of the first civil war against Charles I, in January 1645, Lilburne spoke out against Parliament’s establishment of Presbyterianism with no allowance for religious toleration. Lilburne’s complaint was not with a state-sponsored church but with Parliament’s refusal to allow the free exercise of nonadherents’ beliefs. For the next twelve years, Lilburne wrote extensively regarding the individual’s inherent right to the free exercise of religious beliefs and, consistent with his own continued pamphleteering, freedom of the press.

Lilburne was convicted and exiled for libel

In 1649 Lilburne published two pamphlets accusing Cromwell of treason. Lilburne was acquitted in an initial trial for treason, but was convicted in 1652 for criminal libel and exiled. In defiance of Parliament, he returned the next year. Vowing to “break [Lilburne] into pieces,” Cromwell had him charged with violating an act of Parliament that had forbidden his return, under pain of death. In a public spectacle of a trial, Lilburne was acquitted after four days. Fresh charges were soon brought against him, but Lilburne was again acquitted. Cromwell nonetheless kept him imprisoned, and he remained either in prison or on parole until his death in 1657.

This article was originally published in 2009. Patrick Chinnery is an attorney in Nashville, Tennessee, with a general practice, including litigation of speech-based torts and defending against SLAPP actions. He’s also a former instructor in Middle Tennessee State University’s Political Science Department, teaching U.S. Constitutional Law, Law and the Legal System, U.S. Presidency, and other American government-based classes.