In Barr v. American Association of Political Consultants (2020), the U.S. Supreme Court invalidated a portion of a federal law that allowed robocalls to collect government debts, such as student loans and mortgage debts.

The Court reasoned by a tally of 6-3 that disallowing robocalls made for political and other purposes but allowing robocalls to collect government debts amounted to impermissible content discrimination under the First Amendment. However, the Court also ruled 7-2 that this government-debt exception was severable from the rest of the law and refused to invalidate the entire law generally banning robocalls.

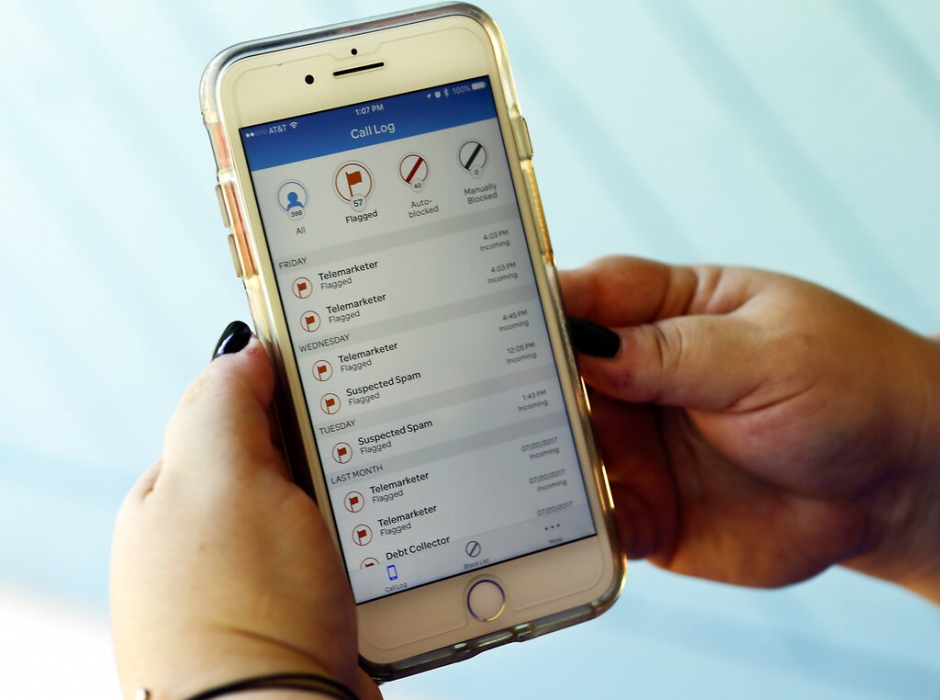

The Telephone Consumer Protection Act of 1991 generally prohibits robocalls, which are automated telephone messages with recorded messages, to cell phones and homes. In 2015, Congress amended the law to allow robocalls to collect government debts.

Political consultants group argued law violated First Amendment

Several political and nonprofit organizations, including the American Association of Political Consultants, challenged the law and the government-debt exception. A federal district court in North Carolina rejected the First Amendment claims, reasoning that the government had a compelling interest in collecting debt.

On appeal, the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals vacated the ruling, finding that the robocall restrictions with the exception for government debt calls was an impermissible content-based restriction on speech that did not satisfy strict scrutiny. The 4th Circuit also determined that the unconstitutionality of the government-debt exception was severable from the rest of the law.

The government petitioned for U.S. Supreme Court review, which was granted. The government argued that the government-debt exception on robocalls was content-neutral.

Court invalidates exception allowing robocalls for government-debt collection

Justice Brett Kavanaugh, in his main opinion for the Court, reasoned that the government-debt exception was a content-based restriction on speech. “The law here focuses on whether the caller is speaking about a particular topic,” he wrote. “In short, the robocall restriction with the government-debt exception is content-based.”

Kavanaugh then noted that the government-debt exception is subject to strict scrutiny and that the exception does not pass that high standard. He noted that the “Government concedes that it cannot satisfy strict scrutiny to justify the government-debt exception.”

However, Kavanaugh agreed with the government that the invalidation of the government-debt exception does not doom the entire restriction on robocalls. Instead, Kavanaugh agreed with the government that the offending government-debt exception provision could be severed from the rest of the law. “The Court’s power and preference to partially invalidate a statute in that fashion has been firmly established since Marbury v. Madison,” he explained.

Kavanaugh explained that “[w]ith the government-debt exception severed, the remainder of the law is capable of functioning independently and thus would be fully operative as a law.” He applied what he termed “traditional severability principles” and left in place the rest of the robocall restriction which he wrote did not constitute unequal treatment.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote an opinion concurring in the judgment. She noted that even under intermediate scrutiny, the government-debt exception fails First Amendment review because it is not narrowly tailored.

Justice Steven Breyer, joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Elena Kagan, wrote an opinion concurring in part and dissenting in part. Breyer disagreed with the majority opinion that the government-debt exception was unconstitutional. However, he agreed with the portion of the opinion that saved the rest of the robocall legislation.

Breyer criticized the majority’s strict application of the content-discrimination principle. Instead, he favored an approach that is more consistent with “First Amendment values” such as the “free marketplace of ideas.”

“To reflexively treat all content-based distinctions as subject to strict scrutiny regardless of context or practical effect is to engage in an analysis untethered from the First Amendment’s objectives,” he wrote. Breyer applied a form of heightened scrutiny, which he later calls “intermediate scrutiny” and upheld the government-debt exception. However, as stated earlier, he agreed the provision was severable from the rest of the statute.

Gorsuch dissent thought entire robocall restrictions should be struck down

Justice Neil Gorsuch, joined by Justice Clarence Thomas, wrote an opinion concurring in the judgment in part and dissenting in part. He agreed with the majority that the law’s “rule against cellphone robocalls is a content-based restriction that fails strict scrutiny” and the “government offers no compelling justification for its prohibition against the plaintiffs’ political speech.”

However, on the remedy question, he dissented. Gorsuch questioned the Court’s application of the severability doctrine which ultimately denied the plaintiffs the ability to engage in their political speech robocalls. “Yet, somehow, in the name of vindicating the First Amendment, our remedial course today leads to the unlikely result that not a single person will be allowed to speak more freely and, instead, more speech will be banned,” he wrote. “Having to tolerate unwanted speech imposes no cognizable constitutional injury on anyone; it is life under the Amendment, which is almost always invoked to protect speech some would rather not hear.”